Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease diagnosed mainly in patients younger than 40 years of age.1

We report 6 cases of thoracic sarcoidosis with onset at advanced age, and analyze how this disease differs in the elderly.

We reviewed 6 patients with sarcoidosis diagnosed after the age of 70 years. Presentation at the time of diagnosis was: erythema nodosum (1 patient), Sjögren's syndrome (1), respiratory symptoms (2) and asymptomatic finding (2). Radiological findings on chest computed tomography revealed sarcoidosis type I in 1 patient, sarcoidosis type II in 4 patients, and sarcoidosis type III in 1 patient. Three patients had atypical radiological findings in the chest computed tomography. All patients had elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels. Bronchoscopy was performed in 4 patients, gallium scintigraphy in 4, and spirometry in 2. To rule out tuberculous infection, sputum culture was performed in 4 patients, all with negative results. Biopsy was performed in 5 patients in total: salivary gland biopsy in 1 patient (negative result), and lung in the others. Techniques used to obtain pulmonary parenchymal biopsies were transbronchial biopsy, cryobiopsy, open lung biopsy, and endobronchial ultrasound-guided bronchoscopy of mediastinal lymphadenopathies. Non-necrotizing granulomas were confirmed on pathology testing. As regards treatment, 4 patients required corticosteroids. Clinical progress was as follows: 3 patients remained stable, 2 improved and 1 worsened. During patient follow-up (ranging between 1.5 and 10 years), 2 patients died for reasons not attributable to sarcoidosis. None of the patients developed pulmonary fibrosis.

Sarcoidosis rarely occurs in elderly patients, and few references are available in the literature. After the age of 65 years, sarcoidosis can be considered elderly-onset.2 Elderly subjects more frequently report general symptoms and it is unusual for disease to be identified by a chance finding in asymptomatic patients.3,4

The diagnostic tests for confirming suspected sarcoidosis and for ruling out infectious or malignant processes are manifold. The most typical radiological findings are lymphadenopathies and small pulmonary nodules distributed around the lymph nodes. Many atypical radiological forms have been described, some of which are more common in patients older than 50 years. ACE levels were elevated in some of our cases, but the utility of this marker in the elderly is questionable, since it can also be elevated in renal failure or diabetes.3

No differences in bronchoalveolar lavage or gallium scintigraphy results have been described in elderly patients.

Granulomatous infections must be ruled out, particularly tuberculosis. Tuberculin testing can give false negatives in the elderly, so cultures for mycobacteria must be performed to rule out infection. Definitive diagnosis requires pathology confirmation and is determined by non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas. The techniques employed will depend on the patient's situation, particularly in more fragile geriatrics. Salivary gland biopsy has been reported to have high diagnostic yield in the literature,3 but in our series it was performed in only 1 patient, with a negative result.

Disease progress is varied and unpredictable. Up to 30% of cases can resolve spontaneously.1 No difference have been described in the progress of elderly patients compared to other age groups.

There is controversy regarding when to start corticosteroid treatment.5 According to some authors, treatment should be reserved for patients with significant clinical or functional compromise or with mild disease that does not remit spontaneously or progresses after 6–12 months. Closer monitoring is recommended in elderly patients, as side effects from steroid treatment are more common in this population.2,4

To conclude, sarcoidosis with thoracic manifestations is an entity which can occur in elderly patients and requires numerous diagnostic tests for confirmation. Some studies have described differences in sarcoidosis in elderly patients compared to other age groups. The interpretation of diagnostic tests may be more complex in these patients due to their high burden of concomitant diseases and the atypical presentation of the disease in this population.

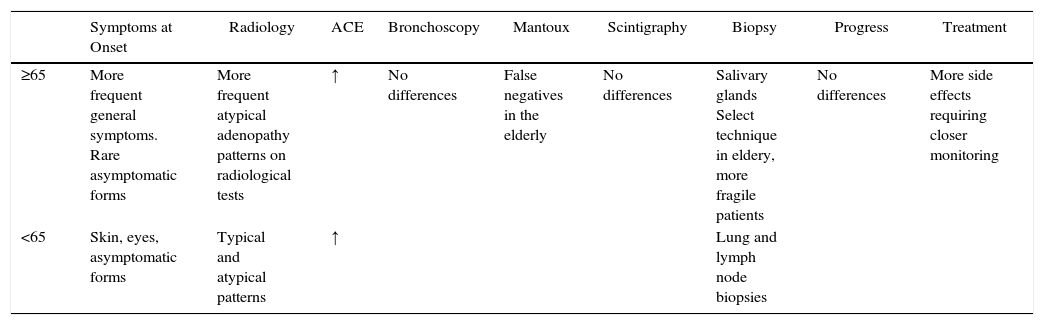

Table 1 shows a summary of the different characteristics of sarcoidosis in the elderly patient.

Differences in Thoracic Sarcoidosis in Elderly Patients (≥65) Compared to Other Age Groups.

| Symptoms at Onset | Radiology | ACE | Bronchoscopy | Mantoux | Scintigraphy | Biopsy | Progress | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥65 | More frequent general symptoms. Rare asymptomatic forms | More frequent atypical adenopathy patterns on radiological tests | ↑ | No differences | False negatives in the elderly | No differences | Salivary glands Select technique in eldery, more fragile patients | No differences | More side effects requiring closer monitoring |

| <65 | Skin, eyes, asymptomatic forms | Typical and atypical patterns | ↑ | Lung and lymph node biopsies |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme, more often encountered in sarcoidosis in the elderly.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Herrero H. Evolución, manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico en ancianos diagnosticados de sarcoidosis con afectación torácica: a propósito de 6 casos. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:491–492.