The objective of the study was to determine the trend of variables related to tuberculosis (TB) from the Integrated Tuberculosis Research Program (PII-TB) registry of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), and to evaluate the PII-TB according to indicators related to its scientific objectives.

MethodCross-sectional, population-based, multicenter study of new TB cases prospectively registered in the PII-TB between 2006 and 2016. The time trend of quantitative variables was calculated using a lineal regression model, and qualitative variables using the χy test for lineal trend.

ResultsA total of 6,892 cases with an annual median of 531 were analyzed. Overall, a significant down-ward trend was observed in women, immigrants, prisoners, and patients initially treated with 3 drugs. Significant upward trends were observed in patients aged 40−50 and >50 years, first visit conducted by a specialist, hospitalization, diagnostic delay, disseminated disease and single extrapulmonary location, culture(+), drug susceptibility testing performed, drug resistance, directly observed treatment, prolonged treatment, and death from another cause. The scientific objectives of the PII-TB that showed a significant upward trend were publications, which reached a maximum of 8 in 2016 with a total impact factor of 49.664, numbers of projects initiated annually, presentations at conferences, and theses.

ConclusionsPII-TB provides relevant information on TB and its associated factors in Spain. A large team of researchers has been created; some scientific aspects of the registry were positive, while others could have been improved.

El objetivo del estudio fue conocer la tendencia de las variables relacionadas con la tuberculosis (TB) en España a partir del registro del Programa Integrado de Investigación en Tuberculosis (PII-TB) de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) y evaluar el PII-TB mediante indicadores relacionados con sus objetivos científicos.

MétodoEstudio transversal multicéntrico de base poblacional de casos nuevos de TB registrados prospectivamente por el PII-TB entre 2006 y 2016. La tendencia temporal de variables cuantitativas se realizó mediante un modelo de regresión lineal y las cualitativas mediante la prueba de χ2 de tendencia lineal.

ResultadosSe analizaron 6.892 casos de TB con una mediana anual de 531. La tendencia general fue significativamente decreciente en mujeres, inmigrantes, privados de libertad y en tratados inicialmente con 3 fármacos. Se incrementaron significativamente la tendencia de grupos de 40–50 años y > 50 años, primera atención por especialista de zona, hospitalización, retraso diagnóstico, localización diseminada y extrapulmonar única, cultivo (+), realización de antibiogramas, resistencia a fármacos, tratamiento directamente observado, prolongación del tratamiento y muerte por otra causa. Los objetivos científicos del PII-TB que incrementaron significativamente fueron las publicaciones alcanzando un máximo de 8 en 2016 y con un factor de impacto total de 49,664, y también mejoraron los proyectos iniciados anualmente, presentaciones en congresos y las tesis o tesinas.

ConclusionesEl PII-TB proporciona información relevante sobre la TB y sus factores asociados en España. Se ha formado un amplio equipo de investigadores y se han detectado aspectos científicos positivos y otros mejorables.

Tuberculosis (TB) is still one of the most important infectious diseases worldwide, and remains a major public health problem: in fact, in 1993 it was declared a global emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO).1

The incidence of TB in Spain in 1996 was 38.48 cases/100,000 inhabitants,2 varying widely among autonomous communities (AC).3 By 1999, it had fallen to 26.7 cases/100,000 inhabitants4 and by 2017, incidence was 9.43 cases/100,000 inhabitants.5 However, the real incidence is probably higher, since under-reporting is significant.6–8 A surge in immigration substantially altered the epidemiology of TB in Spain.9 In Barcelona between 1995 and 2001, for example, rates rose from 5% to 47%,7 and similar figures were observed in some CAs.10

In 2004, the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) created the Integrated Tuberculosis Research Program (PII-TB) with the aim of promoting and prioritizing multidisciplinary and multicenter research. Program objectives include facilitating TB research in Spain, incorporating evaluation into clinical practice, stimulating research training, coordinating TB research, and improving prevention and control.11

As early as 1978, the WHO published guidelines for evaluating health programs and adapting them to management processes,12 an initiative followed by agencies such as the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union).13 This approach was adopted in Spain with the Consensus on Prevention and Control Programs in TB14 and, more recently, the Spanish TB Prevention and Control Plan.15

The objectives of this study were to determine trends in TB prevention and control16 derived from the Spanish PII-TB registry and evaluate the scientific objectives of that program.11

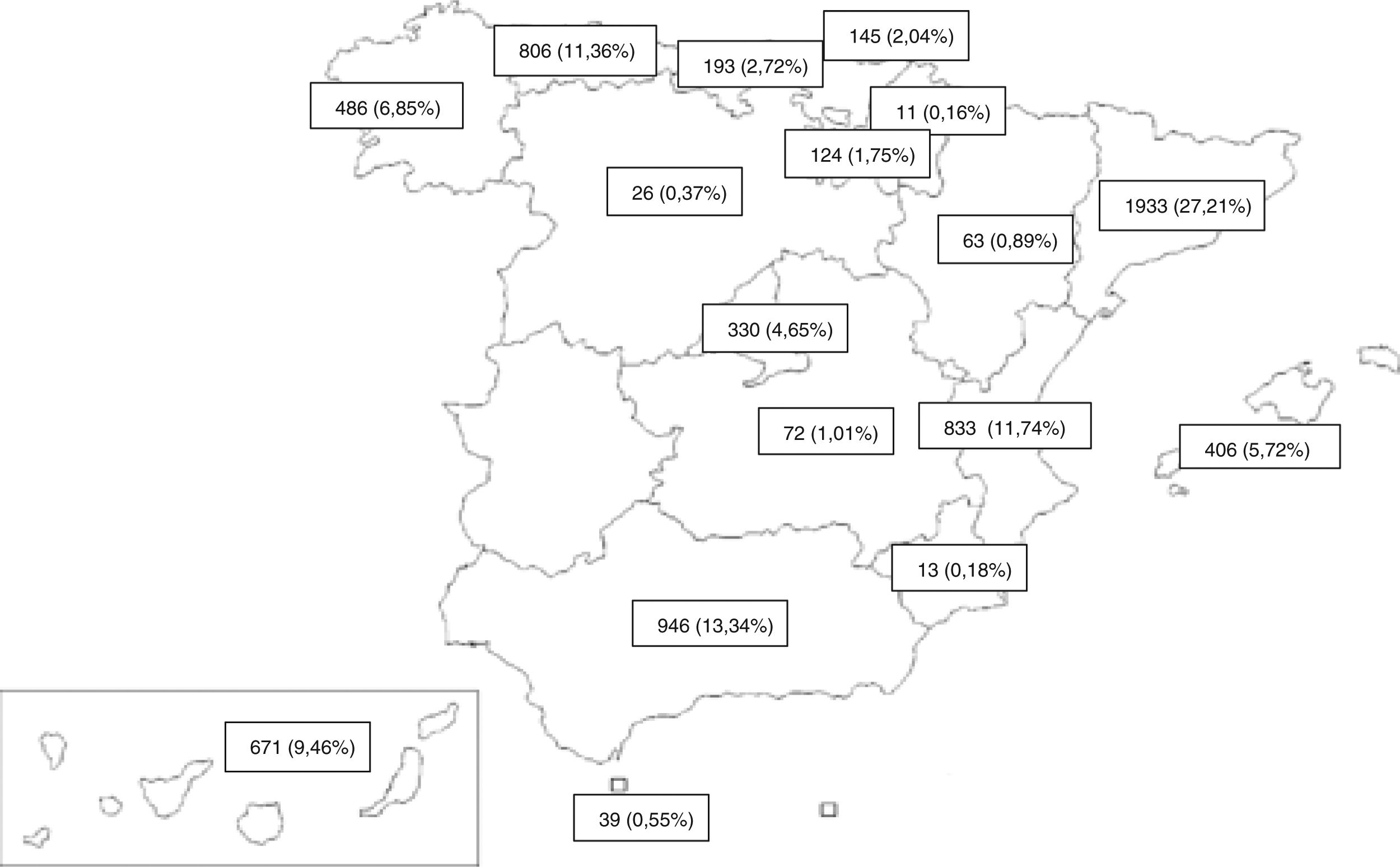

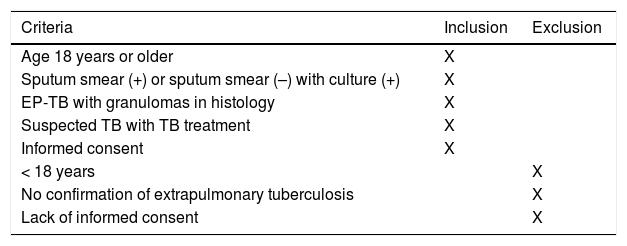

MethodDesignWe performed a population-based, multicenter, cross-sectional study of all new TB cases reported prospectively between 2006 and 2016 by PII-TB investigators in 16 ACs and 1 autonomous city (Fig. 1). Previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria17,18 are listed in Table 1.

Case inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Age 18 years or older | X | |

| Sputum smear (+) or sputum smear (–) with culture (+) | X | |

| EP-TB with granulomas in histology | X | |

| Suspected TB with TB treatment | X | |

| Informed consent | X | |

| < 18 years | X | |

| No confirmation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis | X | |

| Lack of informed consent | X |

A retrospective descriptive analysis of the main variables was performed for each year of the study period and a trend test was then conducted to determine significant, favorable or unfavorable variations in these variables. Similar analyses were performed with indicators of the PII-TB scientific objectives.

Variables and statistical analysis- 1

Variables associated with tuberculosis

Number of cases (total and by age group), sex, country of origin, risk factors (tobacco, alcohol, drugs), associated diseases (human immunodeficiency virus, immunodepression), prior treatment, site, sputum smear, culture, drug susceptibility testing, type of treatment (combination of 3 drugs, isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide [HRZ], or 4 drugs with the addition of ethambutol [HRZE], or non-combined treatments), diagnostic delay, treatment adherence, directly observed treatment (DOT), and treatment outcome (cure, completed treatment, therapeutic failure, transfer, TB or another cause death, dropout, prolongation of treatment, lost-to-follow-up).

- 2

Scientific indicators of the Integrated Tuberculosis Research Program

Participating investigators and centers, publications, presentations at congresses, and theses/dissertations.

Qualitative and quantitative variables and frequency distribution were analyzed, and measures of central tendency, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Proportions were compared using the χ² test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Time trends among quantitative variables were investigated using a simple linear regression model, considering the variables described above as dependent and the period as the independent variable. For qualitative variables, the trend over time was analyzed using the χ² linear trend test. The mean annual decline was calculated by dividing the percentage reduction in incidence between the first and last years by the number of years considered.

SPSS 18 IBM and R freeware version 2.13 (http://cran.r-project.org) statistical packages were used.

Ethical aspectsCases were included according to the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (Tokyo revision, October 2004) and the Spanish Organic Data Protection Act 15/1999. Each patient received detailed information and was asked to consent to the processing of their clinical data. Confidentiality was guaranteed because the surveys contain only the patient's initials, and access is restricted to the investigator and, if necessary, the pertinent Scientific Research Ethics Committee and the health authorities. No reference to patients’ identity was made in the publication of the results.

Results- 1

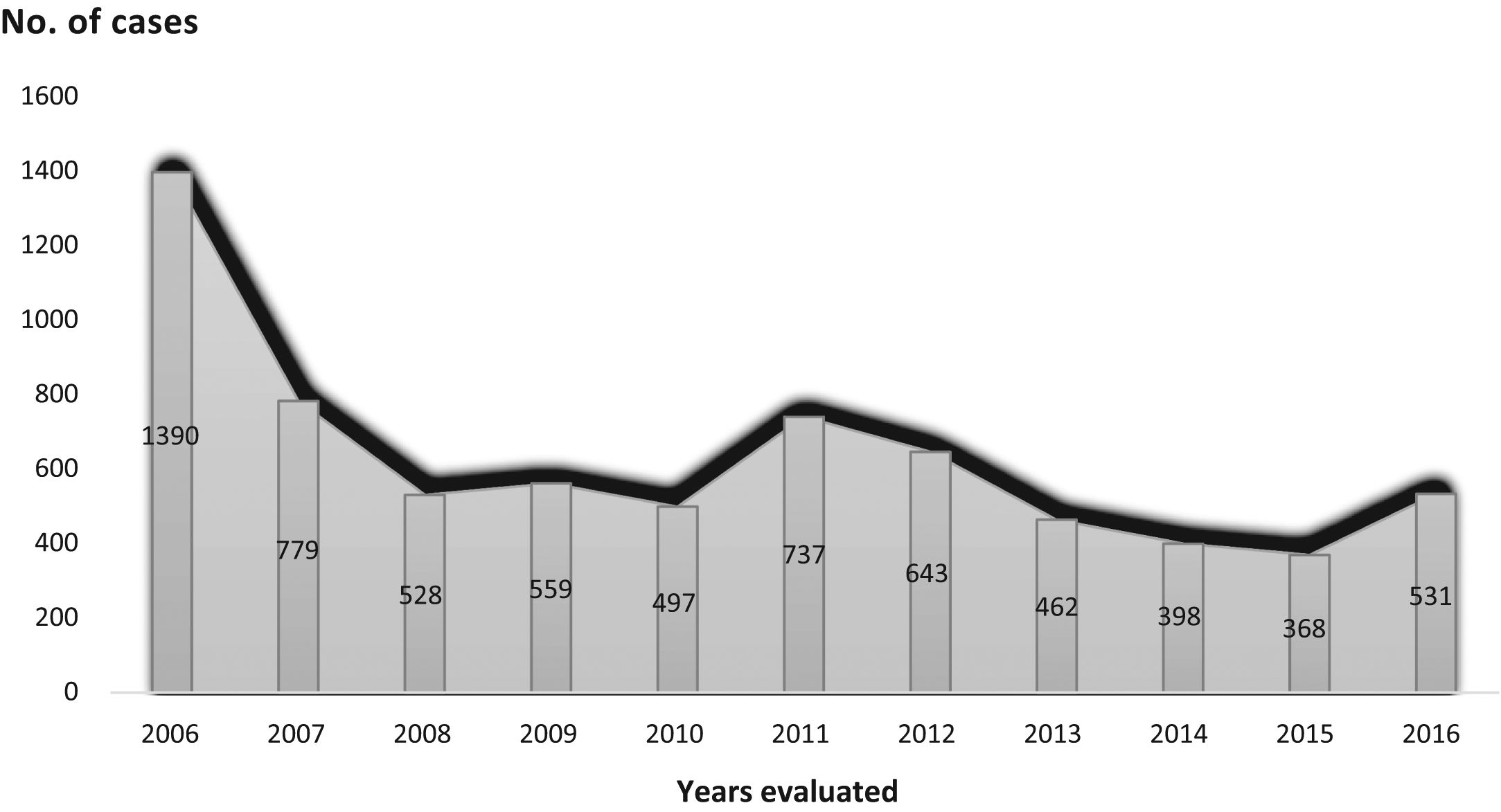

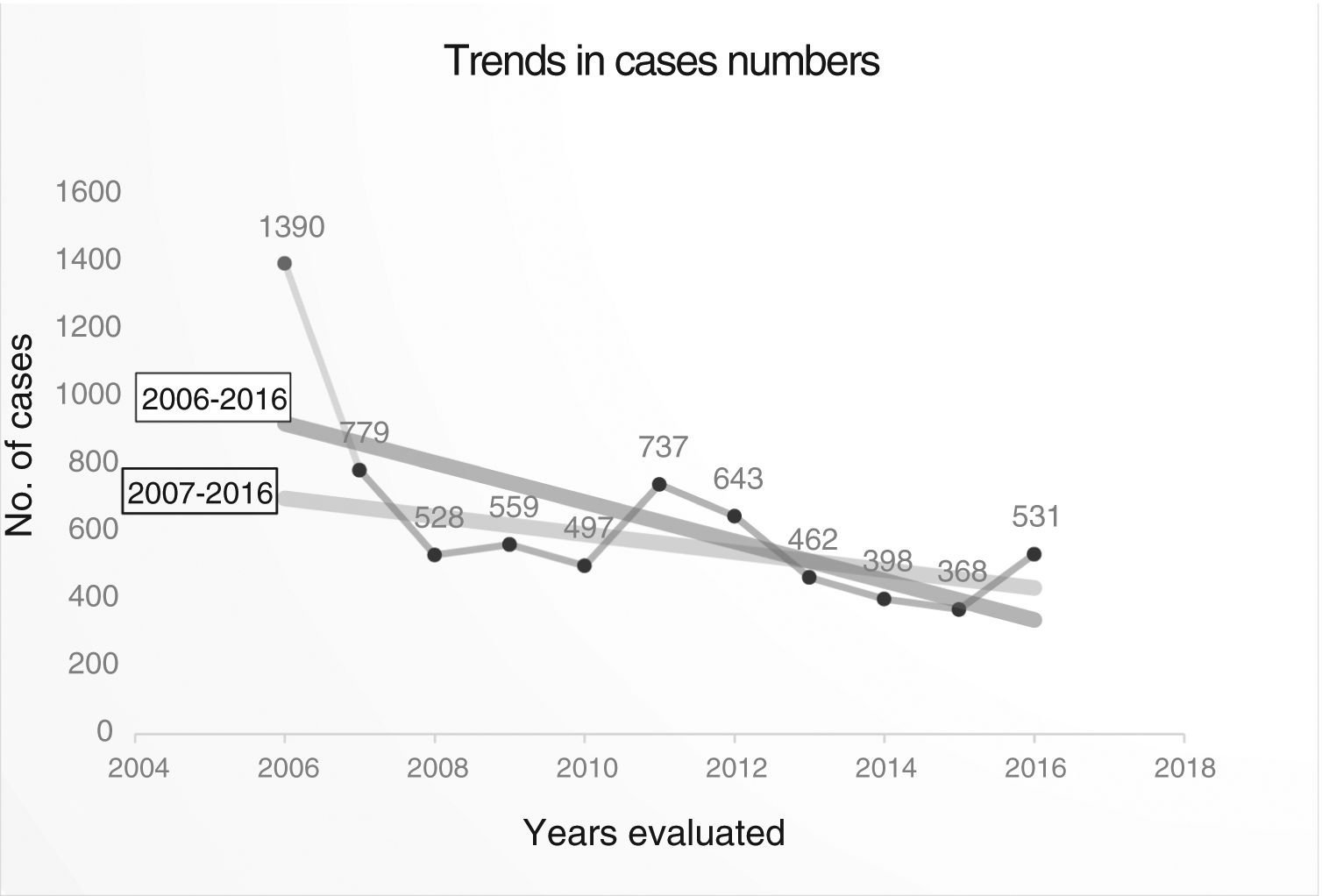

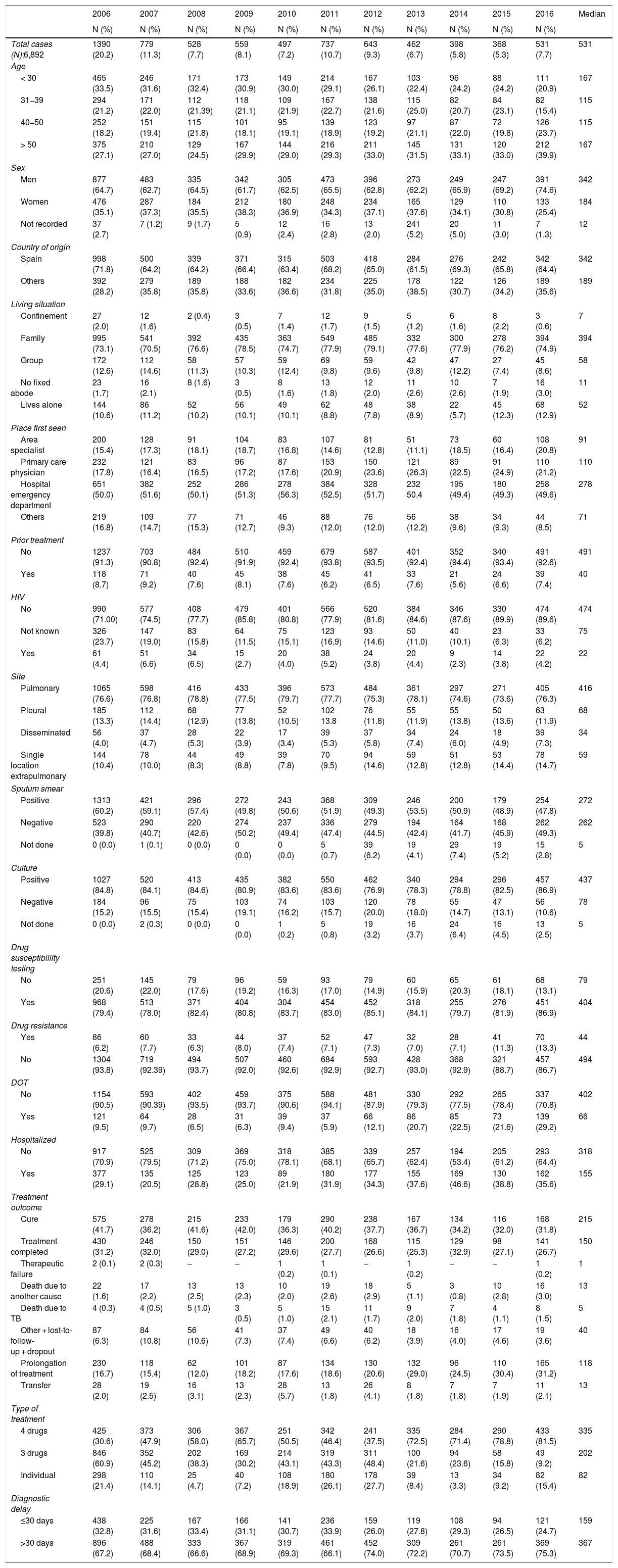

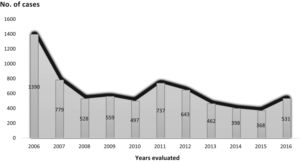

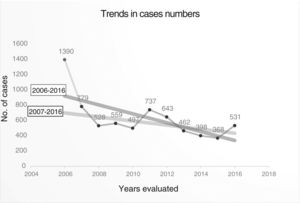

Trend in variables of interest in tuberculosis: number of cases was 6892, with an annual median of 531 (Table 2) (Fig. 2), and a downward trend: y = 974.38−57.97x (Fig. 3).

Table 2.Variables associated with tuberculous disease over the period 2006-2016.

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Median N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) Total cases (N):6,892 1390 (20.2) 779 (11.3) 528 (7.7) 559 (8.1) 497 (7.2) 737 (10.7) 643 (9.3) 462 (6.7) 398 (5.8) 368 (5.3) 531 (7.7) 531 Age < 30 465 (33.5) 246 (31.6) 171 (32.4) 173 (30.9) 149 (30.0) 214 (29.1) 167 (26.1) 103 (22.4) 96 (24.2) 88 (24.2) 111 (20.9) 167 31−39 294 (21.2) 171 (22.0) 112 (21.39) 118 (21.1) 109 (21.9) 167 (22.7) 138 (21.6) 115 (25.0) 82 (20.7) 84 (23.1) 82 (15.4) 115 40−50 252 (18.2) 151 (19.4) 115 (21.8) 101 (18.1) 95 (19.1) 139 (18.9) 123 (19.2) 97 (21.1) 87 (22.0) 72 (19.8) 126 (23.7) 115 > 50 375 (27.1) 210 (27.0) 129 (24.5) 167 (29.9) 144 (29.0) 216 (29.3) 211 (33.0) 145 (31.5) 131 (33.1) 120 (33.0) 212 (39.9) 167 Sex Men 877 (64.7) 483 (62.7) 335 (64.5) 342 (61.7) 305 (62.5) 473 (65.5) 396 (62.8) 273 (62.2) 249 (65.9) 247 (69.2) 391 (74.6) 342 Women 476 (35.1) 287 (37.3) 184 (35.5) 212 (38.3) 180 (36.9) 248 (34.3) 234 (37.1) 165 (37.6) 129 (34.1) 110 (30.8) 133 (25.4) 184 Not recorded 37 (2.7) 7 (1.2) 9 (1.7) 5 (0.9) 12 (2.4) 16 (2.8) 13 (2.0) 241 (5.2) 20 (5.0) 11 (3.0) 7 (1.3) 12 Country of origin Spain 998 (71.8) 500 (64.2) 339 (64.2) 371 (66.4) 315 (63.4) 503 (68.2) 418 (65.0) 284 (61.5) 276 (69.3) 242 (65.8) 342 (64.4) 342 Others 392 (28.2) 279 (35.8) 189 (35.8) 188 (33.6) 182 (36.6) 234 (31.8) 225 (35.0) 178 (38.5) 122 (30.7) 126 (34.2) 189 (35.6) 189 Living situation Confinement 27 (2.0) 12 (1.6) 2 (0.4) 3 (0.5) 7 (1.4) 12 (1.7) 9 (1.5) 5 (1.2) 6 (1.6) 8 (2.2) 3 (0.6) 7 Family 995 (73.1) 541 (70.5) 392 (76.6) 435 (78.5) 363 (74.7) 549 (77.9) 485 (79.1) 332 (77.6) 300 (77.9) 278 (76.2) 394 (74.9) 394 Group 172 (12.6) 112 (14.6) 58 (11.3) 57 (10.3) 59 (12.4) 69 (9.8) 59 (9.6) 42 (9.8) 47 (12.2) 27 (7.4) 45 (8.6) 58 No fixed abode 23 (1.7) 16 (2.1) 8 (1.6) 3 (0.5) 8 (1.6) 13 (1.8) 12 (2.0) 11 (2.6) 10 (2.6) 7 (1.9) 16 (3.0) 11 Lives alone 144 (10.6) 86 (11.2) 52 (10.2) 56 (10.1) 49 (10.1) 62 (8.8) 48 (7.8) 38 (8.9) 22 (5.7) 45 (12.3) 68 (12.9) 52 Place first seen Area specialist 200 (15.4) 128 (17.3) 91 (18.1) 104 (18.7) 83 (16.8) 107 (14.6) 81 (12.8) 51 (11.1) 73 (18.5) 60 (16.4) 108 (20.8) 91 Primary care physician 232 (17.8) 121 (16.4) 83 (16.5) 96 (17.2) 87 (17.6) 153 (20.9) 150 (23.6) 121 (26.3) 89 (22.5) 91 (24.9) 110 (21.2) 110 Hospital emergency department 651 (50.0) 382 (51.6) 252 (50.1) 286 (51.3) 278 (56.3) 384 (52.5) 328 (51.7) 232 50.4 195 (49.4) 180 (49.3) 258 (49.6) 278 Others 219 (16.8) 109 (14.7) 77 (15.3) 71 (12.7) 46 (9.3) 88 (12.0) 76 (12.0) 56 (12.2) 38 (9.6) 34 (9.3) 44 (8.5) 71 Prior treatment No 1237 (91.3) 703 (90.8) 484 (92.4) 510 (91.9) 459 (92.4) 679 (93.8) 587 (93.5) 401 (92.4) 352 (94.4) 340 (93.4) 491 (92.6) 491 Yes 118 (8.7) 71 (9.2) 40 (7.6) 45 (8.1) 38 (7.6) 45 (6.2) 41 (6.5) 33 (7.6) 21 (5.6) 24 (6.6) 39 (7.4) 40 HIV No 990 (71.00) 577 (74.5) 408 (77.7) 479 (85.8) 401 (80.8) 566 (77.9) 520 (81.6) 384 (84.6) 346 (87.6) 330 (89.9) 474 (89.6) 474 Not known 326 (23.7) 147 (19.0) 83 (15.8) 64 (11.5) 75 (15.1) 123 (16.9) 93 (14.6) 50 (11.0) 40 (10.1) 23 (6.3) 33 (6.2) 75 Yes 61 (4.4) 51 (6.6) 34 (6.5) 15 (2.7) 20 (4.0) 38 (5.2) 24 (3.8) 20 (4.4) 9 (2.3) 14 (3.8) 22 (4.2) 22 Site Pulmonary 1065 (76.6) 598 (76.8) 416 (78.8) 433 (77.5) 396 (79.7) 573 (77.7) 484 (75.3) 361 (78.1) 297 (74.6) 271 (73.6) 405 (76.3) 416 Pleural 185 (13.3) 112 (14.4) 68 (12.9) 77 (13.8) 52 (10.5) 102 13.8 76 (11.8) 55 (11.9) 55 (13.8) 50 (13.6) 63 (11.9) 68 Disseminated 56 (4.0) 37 (4.7) 28 (5.3) 22 (3.9) 17 (3.4) 39 (5.3) 37 (5.8) 34 (7.4) 24 (6.0) 18 (4.9) 39 (7.3) 34 Single location extrapulmonary 144 (10.4) 78 (10.0) 44 (8.3) 49 (8.8) 39 (7.8) 70 (9.5) 94 (14.6) 59 (12.8) 51 (12.8) 53 (14.4) 78 (14.7) 59 Sputum smear Positive 1313 (60.2) 421 (59.1) 296 (57.4) 272 (49.8) 243 (50.6) 368 (51.9) 309 (49.3) 246 (53.5) 200 (50.9) 179 (48.9) 254 (47.8) 272 Negative 523 (39.8) 290 (40.7) 220 (42.6) 274 (50.2) 237 (49.4) 336 (47.4) 279 (44.5) 194 (42.4) 164 (41.7) 168 (45.9) 262 (49.3) 262 Not done 0 (0.0) 1 (0.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 5 (0.7) 39 (6.2) 19 (4.1) 29 (7.4) 19 (5.2) 15 (2.8) 5 Culture Positive 1027 (84.8) 520 (84.1) 413 (84.6) 435 (80.9) 382 (83.6) 550 (83.6) 462 (76.9) 340 (78.3) 294 (78.8) 296 (82.5) 457 (86.9) 437 Negative 184 (15.2) 96 (15.5) 75 (15.4) 103 (19.1) 74 (16.2) 103 (15.7) 120 (20.0) 78 (18.0) 55 (14.7) 47 (13.1) 56 (10.6) 78 Not done 0 (0.0) 2 (0.3) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.2) 5 (0.8) 19 (3.2) 16 (3.7) 24 (6.4) 16 (4.5) 13 (2.5) 5 Drug susceptibililty testing No 251 (20.6) 145 (22.0) 79 (17.6) 96 (19.2) 59 (16.3) 93 (17.0) 79 (14.9) 60 (15.9) 65 (20.3) 61 (18.1) 68 (13.1) 79 Yes 968 (79.4) 513 (78.0) 371 (82.4) 404 (80.8) 304 (83.7) 454 (83.0) 452 (85.1) 318 (84.1) 255 (79.7) 276 (81.9) 451 (86.9) 404 Drug resistance Yes 86 (6.2) 60 (7.7) 33 (6.3) 44 (8.0) 37 (7.4) 52 (7.1) 47 (7.3) 32 (7.0) 28 (7.1) 41 (11.3) 70 (13.3) 44 No 1304 (93.8) 719 (92.39) 494 (93.7) 507 (92.0) 460 (92.6) 684 (92.9) 593 (92.7) 428 (93.0) 368 (92.9) 321 (88.7) 457 (86.7) 494 DOT No 1154 (90.5) 593 (90.39) 402 (93.5) 459 (93.7) 375 (90.6) 588 (94.1) 481 (87.9) 330 (79.3) 292 (77.5) 265 (78.4) 337 (70.8) 402 Yes 121 (9.5) 64 (9.7) 28 (6.5) 31 (6.3) 39 (9.4) 37 (5.9) 66 (12.1) 86 (20.7) 85 (22.5) 73 (21.6) 139 (29.2) 66 Hospitalized No 917 (70.9) 525 (79.5) 309 (71.2) 369 (75.0) 318 (78.1) 385 (68.1) 339 (65.7) 257 (62.4) 194 (53.4) 205 (61.2) 293 (64.4) 318 Yes 377 (29.1) 135 (20.5) 125 (28.8) 123 (25.0) 89 (21.9) 180 (31.9) 177 (34.3) 155 (37.6) 169 (46.6) 130 (38.8) 162 (35.6) 155 Treatment outcome Cure 575 (41.7) 278 (36.2) 215 (41.6) 233 (42.0) 179 (36.3) 290 (40.2) 238 (37.7) 167 (36.7) 134 (34.2) 116 (32.0) 168 (31.8) 215 Treatment completed 430 (31.2) 246 (32.0) 150 (29.0) 151 (27.2) 146 (29.6) 200 (27.7) 168 (26.6) 115 (25.3) 129 (32.9) 98 (27.1) 141 (26.7) 150 Therapeutic failure 2 (0.1) 2 (0.3) – – 1 (0.2) 1 (0.1) – 1 (0.2) – – 1 (0.2) 1 Death due to another cause 22 (1.6) 17 (2.2) 13 (2.5) 13 (2.3) 10 (2.0) 19 (2.6) 18 (2.9) 5 (1.1) 3 (0.8) 10 (2.8) 16 (3.0) 13 Death due to TB 4 (0.3) 4 (0.5) 5 (1.0) 3 (0.5) 5 (1.0) 15 (2.1) 11 (1.7) 9 (2.0) 7 (1.8) 4 (1.1) 8 (1.5) 5 Other + lost-to-follow-up + dropout 87 (6.3) 84 (10.8) 56 (10.6) 41 (7.3) 37 (7.4) 49 (6.6) 40 (6.2) 18 (3.9) 16 (4.0) 17 (4.6) 19 (3.6) 40 Prolongation of treatment 230 (16.7) 118 (15.4) 62 (12.0) 101 (18.2) 87 (17.6) 134 (18.6) 130 (20.6) 132 (29.0) 96 (24.5) 110 (30.4) 165 (31.2) 118 Transfer 28 (2.0) 19 (2.5) 16 (3.1) 13 (2.3) 28 (5.7) 13 (1.8) 26 (4.1) 8 (1.8) 7 (1.8) 7 (1.9) 11 (2.1) 13 Type of treatment 4 drugs 425 (30.6) 373 (47.9) 306 (58.0) 367 (65.7) 251 (50.5) 342 (46.4) 241 (37.5) 335 (72.5) 284 (71.4) 290 (78.8) 433 (81.5) 335 3 drugs 846 (60.9) 352 (45.2) 202 (38.3) 169 (30.2) 214 (43.1) 319 (43.3) 311 (48.4) 100 (21.6) 94 (23.6) 58 (15.8) 49 (9.2) 202 Individual 298 (21.4) 110 (14.1) 25 (4.7) 40 (7.2) 108 (18.9) 180 (26.1) 178 (27.7) 39 (8.4) 13 (3.3) 34 (9.2) 82 (15.4) 82 Diagnostic delay ≤30 days 438 (32.8) 225 (31.6) 167 (33.4) 166 (31.1) 141 (30.7) 236 (33.9) 159 (26.0) 119 (27.8) 108 (29.3) 94 (26.5) 121 (24.7) 159 >30 days 896 (67.2) 488 (68.4) 333 (66.6) 367 (68.9) 319 (69.3) 461 (66.1) 452 (74.0) 309 (72.2) 261 (70.7) 261 (73.5) 369 (75.3) 367 DOT: directly observed treatment; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; TB: tuberculosis.

If the number of cases in 2006 is taken as an outlier, the number of cases recorded, without taking into account that year, also showed a downward, though less steep, trend: Y = 53654−26.4x (Fig. 3), with a mean annual decline of 5.61% between 2006 and 2016, and 3.18% between 2007 and 2016. Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3

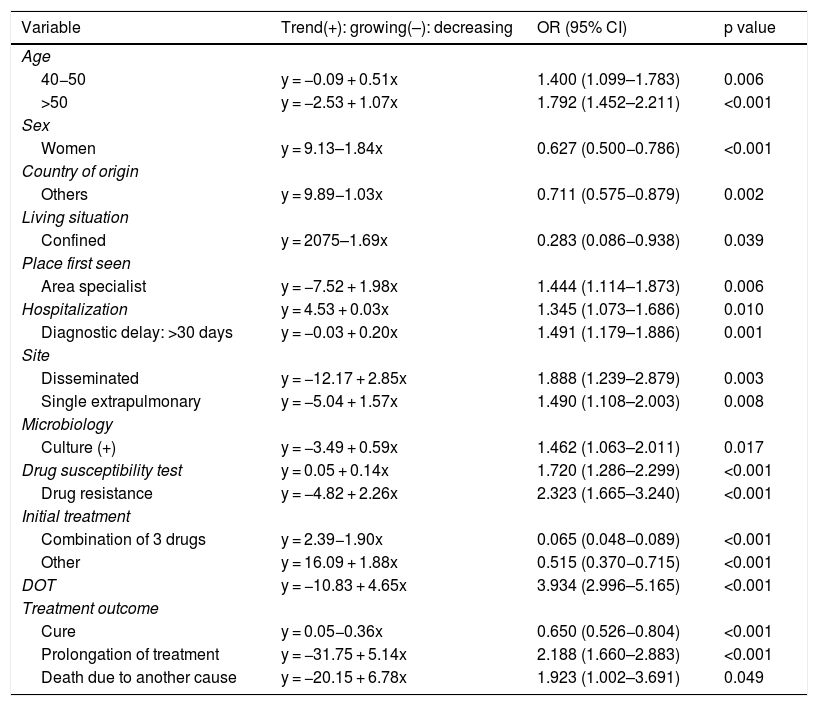

Significant increases were observed among: age groups of 40−50 years and >50 years, first care administered by TB specialist, hospitalization, diagnostic delay of more than 30 days, disseminated TB and single extrapulmonary site, cultures (+), antimicrobial susceptibility, drug resistance, prolongation of treatment, and deaths due to non-TB causes. Significant reductions were observed in: women, immigrants, prisoners, and initial treatment with HRZ at fixed drug doses (Table 3).

- 2

Trends in indicators of scientific objectives

Significant trends in proportions of principal variables analyzed over the period 2006-2016.

| Variable | Trend(+): growing(–): decreasing | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 40−50 | y = −0.09 + 0.51x | 1.400 (1.099–1.783) | 0.006 |

| >50 | y = −2.53 + 1.07x | 1.792 (1.452–2.211) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | y = 9.13–1.84x | 0.627 (0.500−0.786) | <0.001 |

| Country of origin | |||

| Others | y = 9.89−1.03x | 0.711 (0.575−0.879) | 0.002 |

| Living situation | |||

| Confined | y = 2075–1.69x | 0.283 (0.086−0.938) | 0.039 |

| Place first seen | |||

| Area specialist | y = −7.52 + 1.98x | 1.444 (1.114–1.873) | 0.006 |

| Hospitalization | y = 4.53 + 0.03x | 1.345 (1.073–1.686) | 0.010 |

| Diagnostic delay: >30 days | y = −0.03 + 0.20x | 1.491 (1.179–1.886) | 0.001 |

| Site | |||

| Disseminated | y = −12.17 + 2.85x | 1.888 (1.239–2.879) | 0.003 |

| Single extrapulmonary | y = −5.04 + 1.57x | 1.490 (1.108–2.003) | 0.008 |

| Microbiology | |||

| Culture (+) | y = −3.49 + 0.59x | 1.462 (1.063–2.011) | 0.017 |

| Drug susceptibility test | y = 0.05 + 0.14x | 1.720 (1.286–2.299) | <0.001 |

| Drug resistance | y = −4.82 + 2.26x | 2.323 (1.665–3.240) | <0.001 |

| Initial treatment | |||

| Combination of 3 drugs | y = 2.39−1.90x | 0.065 (0.048−0.089) | <0.001 |

| Other | y = 16.09 + 1.88x | 0.515 (0.370−0.715) | <0.001 |

| DOT | y = −10.83 + 4.65x | 3.934 (2.996–5.165) | <0.001 |

| Treatment outcome | |||

| Cure | y = 0.05−0.36x | 0.650 (0.526−0.804) | <0.001 |

| Prolongation of treatment | y = −31.75 + 5.14x | 2.188 (1.660–2.883) | <0.001 |

| Death due to another cause | y = −20.15 + 6.78x | 1.923 (1.002–3.691) | 0.049 |

CI: confidence interval; DOT: directly observed treatment; OR: odds ratio.

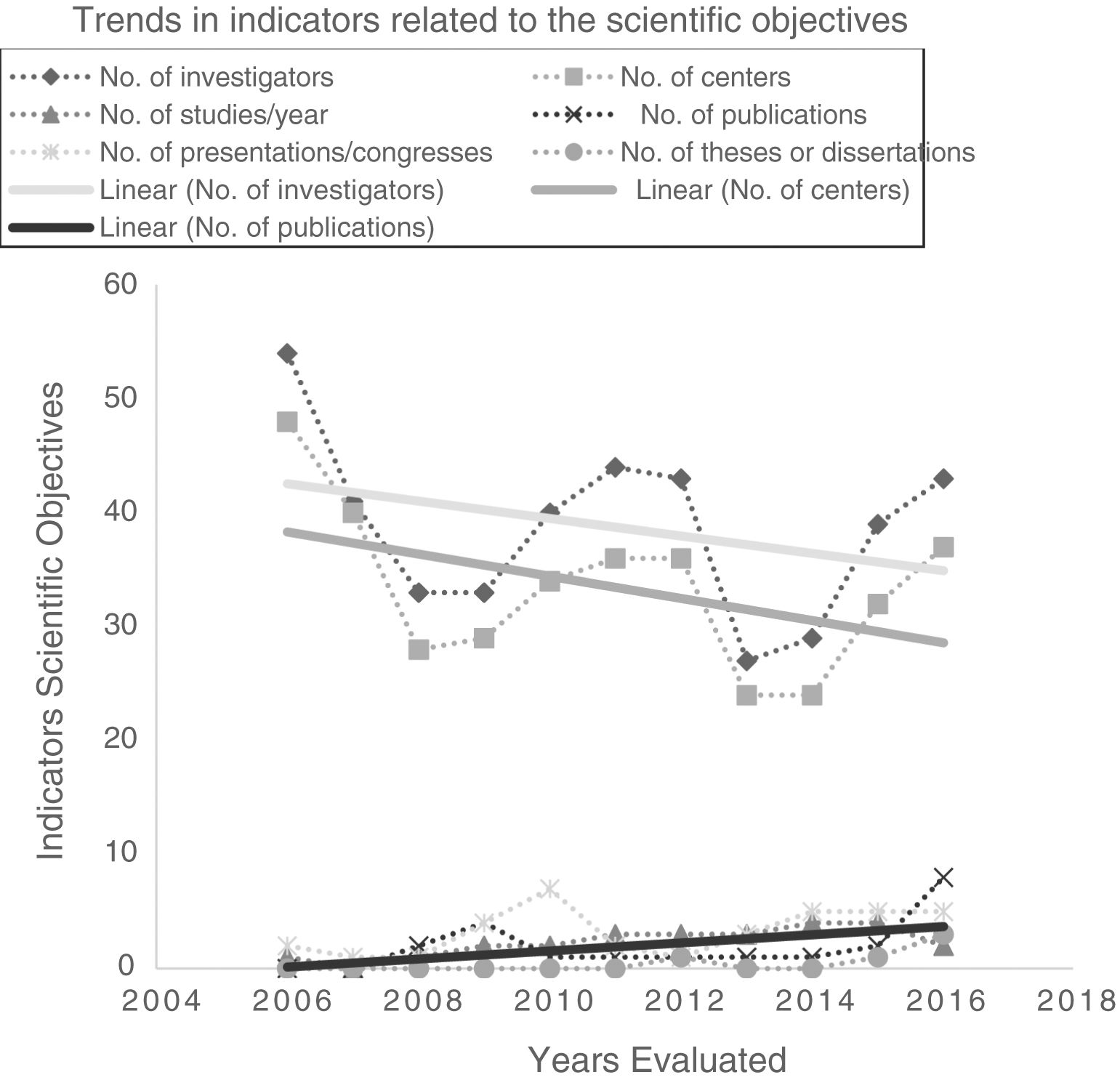

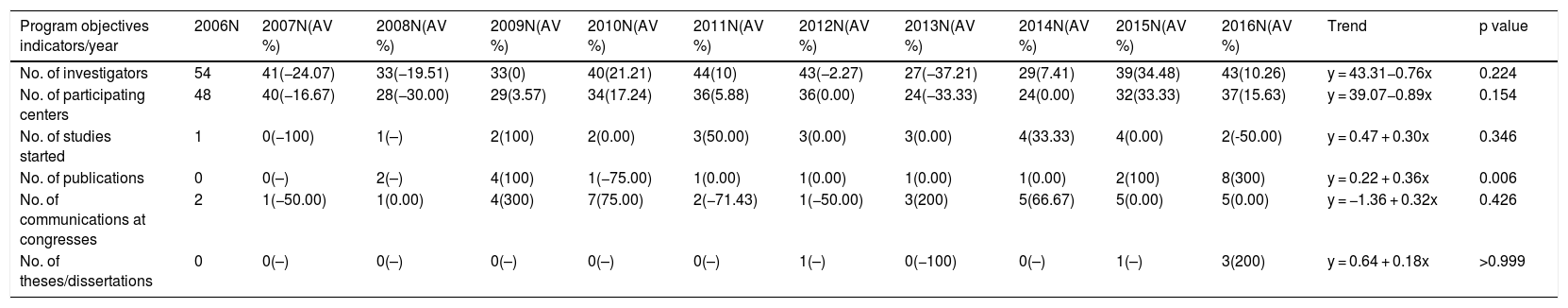

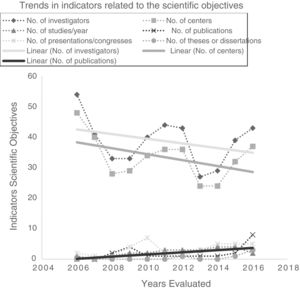

Investigators and participating centers showed a downward trend, but annual publications increased significantly to a maximum of 8 in 2016 (total impact factor: 49.664). The following also showed some improvement, although this was not significant: number of projects initiated annually, presentations at congresses, and theses/dissertations (Table 4; Fig. 4).

Description, annual variation and trends in PII-TB objective indicators (2006-2016).

| Program objectives indicators/year | 2006N | 2007N(AV %) | 2008N(AV %) | 2009N(AV %) | 2010N(AV %) | 2011N(AV %) | 2012N(AV %) | 2013N(AV %) | 2014N(AV %) | 2015N(AV %) | 2016N(AV %) | Trend | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of investigators | 54 | 41(−24.07) | 33(−19.51) | 33(0) | 40(21.21) | 44(10) | 43(−2.27) | 27(−37.21) | 29(7.41) | 39(34.48) | 43(10.26) | y = 43.31−0.76x | 0.224 |

| No. of participating centers | 48 | 40(−16.67) | 28(−30.00) | 29(3.57) | 34(17.24) | 36(5.88) | 36(0.00) | 24(−33.33) | 24(0.00) | 32(33.33) | 37(15.63) | y = 39.07−0.89x | 0.154 |

| No. of studies started | 1 | 0(−100) | 1(–) | 2(100) | 2(0.00) | 3(50.00) | 3(0.00) | 3(0.00) | 4(33.33) | 4(0.00) | 2(-50.00) | y = 0.47 + 0.30x | 0.346 |

| No. of publications | 0 | 0(–) | 2(–) | 4(100) | 1(−75.00) | 1(0.00) | 1(0.00) | 1(0.00) | 1(0.00) | 2(100) | 8(300) | y = 0.22 + 0.36x | 0.006 |

| No. of communications at congresses | 2 | 1(−50.00) | 1(0.00) | 4(300) | 7(75.00) | 2(−71.43) | 1(−50.00) | 3(200) | 5(66.67) | 5(0.00) | 5(0.00) | y = −1.36 + 0.32x | 0.426 |

| No. of theses/dissertations | 0 | 0(–) | 0(–) | 0(–) | 0(–) | 0(–) | 1(–) | 0(−100) | 0(–) | 1(–) | 3(200) | y = 0.64 + 0.18x | >0.999 |

AV %: interannual variation: percentage change from previous year.

In this study, we evaluated the first 11 years of the PII-TB registry, the first SEPAR integrated research program to be assessed. PII-TB data were used to evaluate the evolution of important variables related to TB in Spain and the scientific objectives of the program19.

Our findings highlight the downward trend in annual case numbers, suggesting that the disease is being positively controlled. Similar trends have been observed in other long-term active surveillance programs conducted in Barcelona and Galicia20,21 and by the Ministry of Health.22,23

The inclusion of cases varies widely and could be related to the degree of interest among pulmonologists in each CA (Fig. 1). The annual variability in the number of cases might be due to the existence or absence of funding for case finding, the interest in the different studies conducted, and the extent to which investigators remained motivated after so many years of voluntary participation. Indeed, the number of cases in 2006 could be considered as an outlier because in that year an incentive was paid per case included, a factor that could have boosted motivation, and with it the number of cases included. Excluding 2006 shows a flatter decline that is likely to be closer to reality (Fig. 3). The steepest decline in case numbers occurs among women, suggesting that socio-cultural issues may be at play.24

The downward trend in cases among immigrants could be related to the economic crisis that led to fewer immigrants coming to Spain25 and to limitations in access to healthcare imposed in recent years in various CAs.26 Mass immigration that occurred in some periods probably influenced the increase in drug resistance.27

The downward trend among younger individuals and the upward trend among older people would suggest that transmission is more controlled: recent transmission is increasing while endogenous reactivation is increasing.28

It is interesting to see that hospitalization rates are increasing, even though first-line management should be outpatient care. This could be due to the inclusion of cases from centers that see particularly complicated patients, but the growing diagnostic delay could also play a role, since it would mean that patients are seen when their TB is more advanced, and as such require admission and hospital stays longer than 15 days.29 Similarly, growing trends in disseminated and extrapulmonary TB have recently been observed.23

Two of the indicators for evaluating TB control programs are a diagnostic delay of less than 30 days and DOT in patients with factors associated with lack of compliance.30 This study shows that DOT increased in the years evaluated, but according to another PII-TB study, diagnostic delay also increased,31 which may lead to transmission and epidemic outbreaks.32–34

The latest WHO global report35 specifies drug susceptibility testing as one of the mainstays of TB control, and according to this study these procedures are being implemented more frequently, although the 100% target has never been reached.

Despite national36 and international37 recommendations for prescribing 4-drug combinations, a PII-TB study showed that until 2012 a high proportion of patients were treated with 3 drugs.38 Use of this regimen has now decreased significantly, possibly due to recommendations made since the publication of that particular working group study.

Some centers no longer participate in the project because the investigator has terminated his or her involvement (due to a change of hospital, retirement or illness), and it seems that project leaders have been unable to generate sufficient interest to ensure its continuity. The accreditation of TB units, promoted by SEPAR,39 may facilitate a more stable collaboration.

Indicators of scientific objectives have evolved favorably. The number of publications40 has increased significantly, and although the number of conference communications and thesis/dissertations has increased, particularly in the last year, there is room for improvement.

Retrospective analysis makes it easier to collect information, but disadvantages include difficulty in recovering missing data, the subjectivity of professionals in the interpretation of some activities, and the exclusive inclusion of cases diagnosed by registry participants. These limitations were minimized by constant monitoring of the database and close coordination with investigators.

In conclusion, this study shows that the SEPAR PII-TB registry provides important information on the evolution of TB in Spain. Some factors are positive: a downward trend in case numbers, greater numbers of cases first seen by area specialists, and the increasing use of DOT. However, others are negative: longer diagnostic delay and longer hospitalizations, drug resistance, and the need to prolong treatment. With regard to the PII-TB registry, we must encourage the participation of new collaborators, and continue evaluating this program, in order to improve monitoring and research into this old disease.

FundingThis study was funded by a SEPAR grant: 415/2017.

AuthorshipTR: study conception, analysis of results, and preparation of the manuscript. JMGG, JAC, JRM, LA, MMG, JAG, MAJ, JFM, IM, AP, FS, MLS and JAC: analysis of results, critical reading, review of various versions, and final approval of the manuscript. PII-TB Working Group: data collection.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

R. Agüero (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander); J.L. Alcázar (Instituto Nacional de Silicosis, Oviedo); N. Altet (Unidad de Prevención y Control de la Tuberculosis, Barcelona); L. Altube (Hospital Galdakao, Galdakao); F. Álvarez Navascués (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés, Asturias); M. Barrón (Hospital San Millán-San Pedro, Logroño); P. Bermúdez (Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Malaga), R. Blanquer (Hospital Dr. Peset, Valencia); L. Borderías (Hospital San Jorge, Huesca); A. Bustamante (Hospital Sierrallana, Torrelavega); J.L. Calpe (Hospital La Marina Baixa, Villajoyosa); F. Cañas (Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); F. Casas (Hospital Clínico San Cecilio, Granada), X. Casas (Hospital de Sant Boi, Sant Boi de Llobregat), E. Cases (Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia); R. Castrodeza (Hospital El Bierzo Ponferrada-León, Ponferrada); J.J. Cebrián (Hospital Costa del Sol, Marbella); J.E. Ciruelos (Hospital de Cruces, Guetxo); A.E. Delgado (Hospital Santa Ana, Motril); D. Díaz (Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, Corunna); B. Fernández (Hospital de Navarra, Pamplona); A. Fernández (Hospital Río Carrión, Palencia); J. Gallardo (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara); M. Gallego (Corporación Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell); C. García (Hospital General Isla Fuerteventura, Puerto del Rosario); F.J. García (Hospital Universitario de la Princesa, Madrid); F.J. Garros (Hospital Santa Marina, Bilbao); C. Hidalgo (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), M. Iglesias (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander); G. Jiménez (Hospital de Jaén); J.M. Kindelan (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba); J. Laparra (Hospital Donostia-San Sebastián, San Sebastian); R. Lera (Hospital Dr. Peset, Valencia), T. Lloret (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); M. Marín (Hospital General de Castellón, Castellón); J.T. Martínez (Hospital Mutua de Terrassa, Terrassa); E. Martínez (Hospital de Sagunto, Sagunto); A. Martínez (Hospital de La Marina Baixa, Villajoyosa); C. Melero (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid); C. Milà (Unidad de Prevención y Control de la Tuberculosis, Barcelona); C. Morales (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), M.A. Morales (Hospital Cruz Roja Inglesa, Ceuta); V. Moreno (Hospital Carlos III, Madrid); A. Muñoz (Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Malaga), L. Muñoz (Hospital Reina Sofía, Cordoba); C. Muñoz (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); J.A. Muñoz (Hospital Universitario Central, Oviedo); I. Parra (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar); J.A. Pérez (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia); P. Rivas (Hospital Virgen Blanca, Leon); J. Rodríguez (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); J. Sala (Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, Tarragona); M. Sánchez (Unidad de Tuberculosis Distrito Poniente, Almería); P. Sánchez (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); F. Sanz (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); M. Somoza (Consorcio Sanitario de Tarrasa, Barcelona), E. Trujillo (Complejo Hospitalario de Ávila, Ávila); E. Valencia (Hospital Carlos III, Madrid); A. Vargas (Hospital Universitario Puerto Real, Cádiz); I. Vidal (Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, Corunna); R. Vidal (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona); M.A. Villanueva (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés, Asturias); A. Villar (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona); M. Vizcaya (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Albacete); M. Zabaleta (Hospital de Laredo, Laredo); G. Zubillaga (Hospital Donostia-San Sebastián, San Sebastian).

Please cite this article as: Rodrigo T, García-García J-M, Caminero JA, Ruiz-Manzano J, Anibarro L, García-Clemente MM, et al. Evaluación del Programa Integrado de Investigación en Tuberculosis promovido por la sociedad española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica tras 11 años de funcionamiento. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:483–492.

Members of the Integrated Tuberculosis Research Program (PII-TB) Working Group are listed in Appendix A.