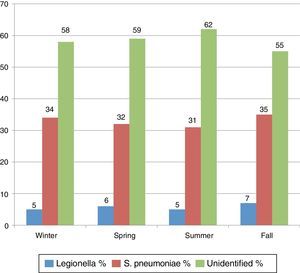

We read with interest the manuscript of Herrera-Lara et al.1 recently published in Archivos de Bronconeumología. We welcome this study, which shows the influence of season and climate on the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), although only in patients admitted to the pneumology ward. This is one limitation recognized by the authors. Another is the lack of follow-up of patients discharged from the emergency department (ED), that account for more than 50% of the CAP cases seen in those units.2 These data are in line with the data of our group,3 and show the quantitative importance of this subgroup when calculating the overall etiology of the disease. Several factors must be taken into consideration when determining CAP etiology, including climate, season, age, place of employment, treatment, comorbidity, patient characteristics, concurrent viral epidemic, etc.4 The most recent consensus guidelines for CAP point out that Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common pathogen in outpatients (including those discharged), hospitalized patients, and intensive care patients (35, 43 and 42% of isolates, respectively). They also mention the increasing importance of Legionella pneumophila, which accounts for 6, 8 and 8% of the cases classified as above, respectively. These figures are consistent with those published by Herrera-Lara et al.,1 who reported that 8.6% of cases are caused by L. pneumophila. Here, in Toledo, the climate tends toward colder, wetter winters and warmer, wetter summers: the average winter temperature in Toledo in 2009–2011 was 7.20°C compared to the mean 9.72°C reported in the study of Herrera-Lara et al.,1 and accumulated rainfall was 54.3L compared to their 35.2L; average summer temperatures were 26.23°C vs 24.6°C, and rainfall was 15.9L vs 8.27L, respectively. We have studied the incidence of CAP according to the seasonal pattern and differences in frequency between S. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila, using the databases of several studies on the management of CAP in the years 2009–2011.3,5S. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila were systematically investigated in all patients with sepsis, admitted with pneumococcus and L. pneumophila serogroup 1 antigens in urine (membrane immunochromatograpy-Binax NOW®). Blood and sputum cultures with direct seeding were requested for inpatients when possible (Legionella: direct immunofluorescence of Legionella pneumophila antigen), and 1698 CAP cases from ED were included (51% were admitted to hospital and etiologic diagnosis was obtained in 39.5%). The seasonal distribution compared with the study of Herrera-Lara et al.1 was as follows: winter (38 vs 36.6%), spring (25 vs 20.2%), summer (8 vs 18.5%) and fall (31 vs 24.7%). Fig. 1 shows a similar distribution pattern for both in all seasons (P=NS). Other diagnoses, such as atypical bacteria (2.5% for Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae) and viral infection (0.5%–1%), showed no seasonal differences, although their proportions are likely to be underestimated, as they were not studied systematically. In conclusion, CAP etiology is influenced not only by the climate and season, but also by geographical location and other factors.

Please cite this article as: Julián-Jiménez A, Flores Chacartegui M, Piqueras-Martínez AN. Patrón etiológico de la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad: importancia del factor geográfico. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:156–157.