After an episode of symptomatic acute pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), patients need a minimum of 3–6 months of anticoagulant treatment, provided that there is no absolute contraindication for their use.1,2 This is the moment when clinicians must make one of the most important decisions in the management of patients with venous thromboembolic disease (VTE): the duration of anticoagulation. Although indefinite anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists reduces the risk of recurrences by approximately 90%, their use increases the risk of major bleeding by 2–6-fold.1 Moreover, anticoagulants “protect” patients only while they are using them,3 so the decision consists not of establishing a definitive period of treatment (e.g., 9 months, 12 months, 24 months), but whether to discontinue anticoagulation or indicate it indefinitely (i.e., with no determined time for discontinuation). This decision should take account of the risk of recurrence (when anticoagulation is discontinued), the risk of bleeding (if it is maintained), and the patient's own preferences.1

The risk/benefit balance is clear in some subgroups of patients. Patients diagnosed with a PTE caused by a major, transitory, and now resolved risk factor have a very low risk of recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued (about 1% in the first year and 3% in the next 5 years),4 and clinical practice guidelines recommend discontinuation after 3 months of treatment. At the other end of the spectrum are patients with a persistent major risk factor (e.g., active cancer, antiphospholipid syndrome, a history of 2 or more idiopathic thrombotic events). These patients have a very high risk of recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued, and should receive treatment indefinitely, or until the risk factor has resolved (e.g., cancer is cured), provided the risk of bleeding is not high. Patients with idiopathic PTE have a 10% risk of recurrence in the first year, and 30% in the 5 years following discontinuation of anticoagulation,5 and clinical practice guidelines recommend indefinite anticoagulant treatment. We recommend indefinite anticoagulation in all men with idiopathic PTE (without a high risk of bleeding), as they have a 2.2-fold risk of recurrence compared to women.6

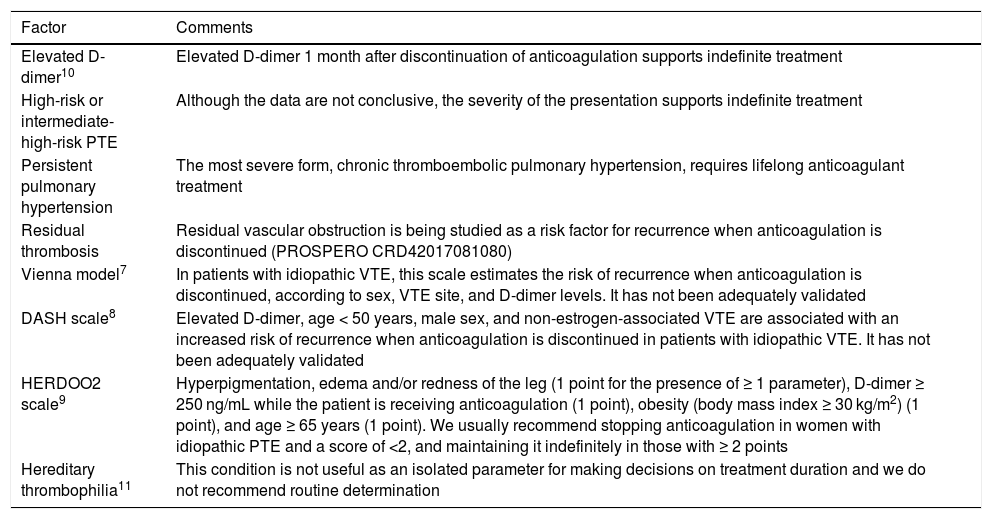

Some subgroups of patients may benefit from additional information to better assess the risk of recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued, either in isolation (clinical characteristics, D-dimer, thrombophilia studies) or in combination, in the form of predictive scales (Vienna model,7 DASH,8 HERDOO29) (Table 1):

- 1

Women with a history of idiopathic PTE.

- 2

Patients with a history of PTE caused by a minor, transitory, and resolved risk factor (e.g., estrogen use, long trips, immobilization, minor surgery) (5% risk of recurrence in the first year and 15% in the first 5 years after discontinuation of anticoagulation).

- 3

Patients who want to stop anticoagulation (regardless of their risk of recurrence).

- 4

Patients with a narrow risk/benefit relationship for the use of indefinite anticoagulant therapy (e.g., patients with moderate risk of bleeding).

Factors guiding the use of indefinite anticoagulation.a

| Factor | Comments |

|---|---|

| Elevated D-dimer10 | Elevated D-dimer 1 month after discontinuation of anticoagulation supports indefinite treatment |

| High-risk or intermediate-high-risk PTE | Although the data are not conclusive, the severity of the presentation supports indefinite treatment |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension | The most severe form, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, requires lifelong anticoagulant treatment |

| Residual thrombosis | Residual vascular obstruction is being studied as a risk factor for recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued (PROSPERO CRD42017081080) |

| Vienna model7 | In patients with idiopathic VTE, this scale estimates the risk of recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued, according to sex, VTE site, and D-dimer levels. It has not been adequately validated |

| DASH scale8 | Elevated D-dimer, age < 50 years, male sex, and non-estrogen-associated VTE are associated with an increased risk of recurrence when anticoagulation is discontinued in patients with idiopathic VTE. It has not been adequately validated |

| HERDOO2 scale9 | Hyperpigmentation, edema and/or redness of the leg (1 point for the presence of ≥ 1 parameter), D-dimer ≥ 250 ng/mL while the patient is receiving anticoagulation (1 point), obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) (1 point), and age ≥ 65 years (1 point). We usually recommend stopping anticoagulation in women with idiopathic PTE and a score of <2, and maintaining it indefinitely in those with ≥ 2 points |

| Hereditary thrombophilia11 | This condition is not useful as an isolated parameter for making decisions on treatment duration and we do not recommend routine determination |

VTE: venous thromboembolic disease; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

In these groups, the accumulation of risk factors for recurrence leads us to favor indefinite treatment, while the absence of these factors makes us inclined to suspend anticoagulation.

In any case, none of the recommendations or predictors of recurrence mentioned above should be applied in a dogmatic manner and clinical experience should always be used to make the best decision on the duration of anticoagulation.

Please cite this article as: Quezada A, Jiménez D. Duración de la anticoagulación tras una tromboembolia de pulmón: una decisión no siempre sencilla. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:617–618.