Chronic cough (CC), or cough lasting more than 8 weeks, has attracted increased attention in recent years following advances that have changed opinions on the prevailing diagnostic and therapeutic triad in place since the 1970s. Suboptimal treatment results in two thirds of all cases, together with a new notion of CC as a peripheral and central hypersensitivity syndrome similar to chronic pain, have changed the approach to this common complaint in routine clinical practice. The peripheral receptors involved in CC are still a part of the diagnostic triad. However, both convergence of stimuli and central nervous system hypersensitivity are key factors in treatment success.

La tos crónica (TC), o tos que perdura más de 8semanas, ha merecido un interés creciente en los últimos años debido a los avances producidos que han motivado un cambio de visión respecto a la clásica tríada diagnóstica y terapéutica en vigor desde la década de los setenta. Unos resultados no óptimos en el tratamiento que alcanza los dos tercios de casos, junto a una nueva concepción de la TC como síndrome de hipersensibilidad con 2 polos, periférico y central, similares al dolor crónico, ocasionan que se contemple este problema tan frecuente en la práctica clínica de una nueva manera. Los receptores periféricos de la TC siguen teniendo vigencia bajo la tríada diagnóstica; sin embargo, tanto la convergencia de estímulos como la hipersensibilidad adquirida a nivel del sistema nervioso central son hechos que tienen una repercusión clave en el éxito del tratamiento.

Chronic cough (CC), or cough lasting more than 8 weeks, is the most common symptom encountered in outpatient medical practice. Research into the mechanisms causing chronic pain and CC has detected similar neuronal pathways in both conditions, enabling investigational advances in chronic pain to be used to improve the understanding of CC. These guidelines discuss the medical problems associated with CC, either as an isolated entity or as the major symptom of a syndrome, and make proposals that take into account the level of evidence and grade of recommendations (GRADE system).1 In this respect, it should be pointed out that in CC, the available evidence is based mainly on observational studies.2

These guidelines are presented in 3 sections: (a) description and management of CC; (b) management of CC in the various clinical care scales; and (c) problems and future perspectives in CC.

Each section may contain several subsections.

Description and Management of Chronic CoughDefinitionCough is an inherent protective respiratory tract symptom. Duration of cough has been defined as acute (lasting up to 4 weeks), subacute (up to 8 weeks), and chronic (more than 8 weeks).3 In this document, CC will be called specific, if it is associated with a known cause, or non-specific, if not. Finally, we will examine current knowledge and the available guidelines on refractory CC (RCC), i.e., CC that persists despite treatment targeting known associated conditions.

EpidemiologyCC is a very common symptom in clinical practice, and prevalence in the general population ranges from 12% to 3.3%.4,5 It is closely related with tobacco use, and the prevalence of CC in smokers is 3 times that of never-smokers or former smokers.6 A higher prevalence of CC has also been associated with environmental pollution.7

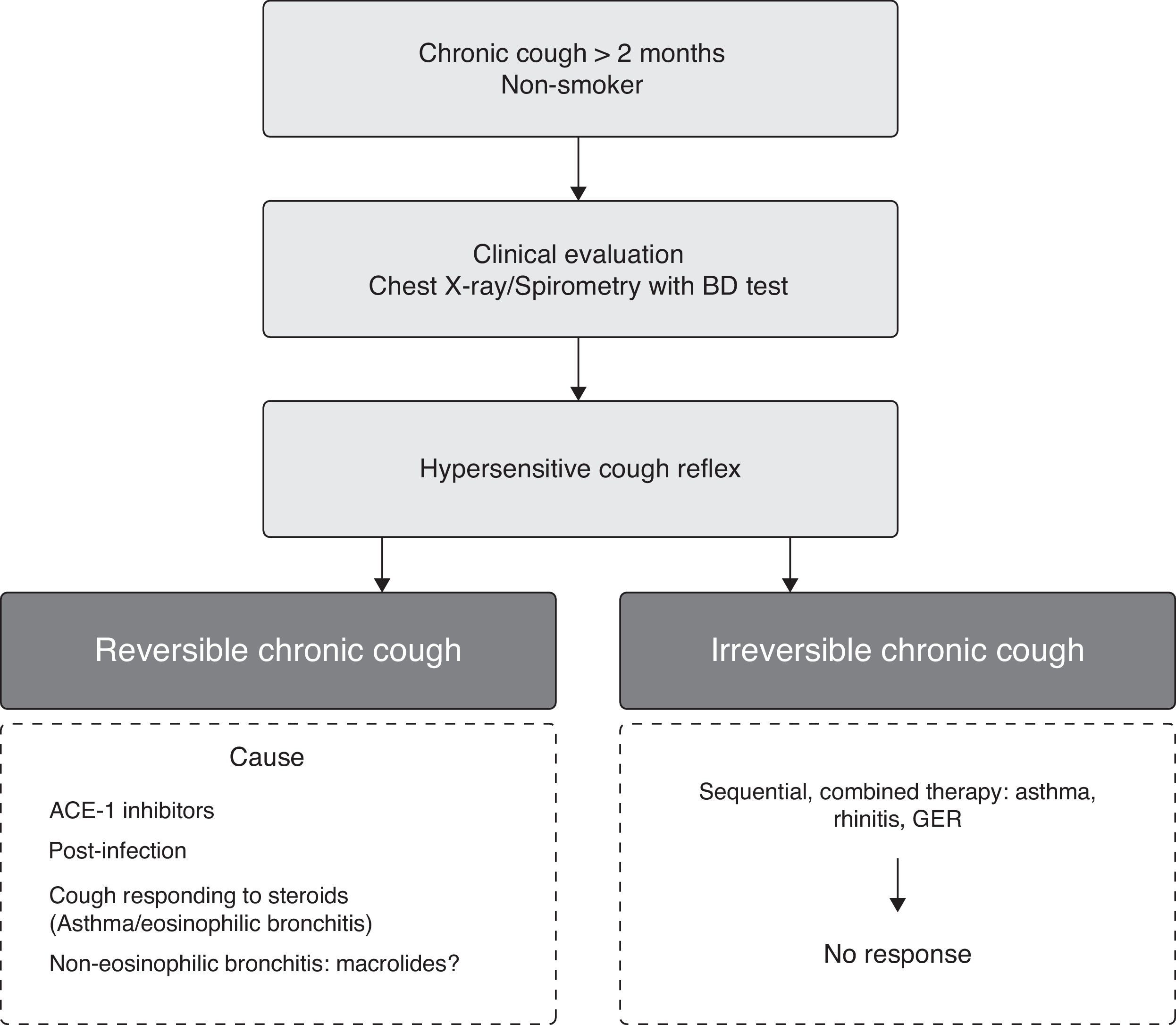

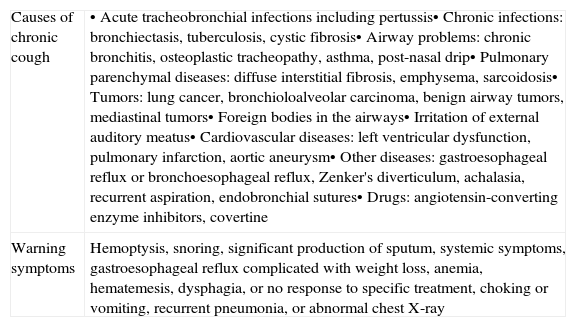

During the initial contact with the CC patient, the physician should determine the general causes of CC and the associated warning symptoms (Table 1). In all CC guidelines currently in use, if the patient has a normal chest X-ray, does not smoke and is not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), the causes associated with CC that will directly impact on the initial treatment are considered.

Causes of chronic cough and warning symptoms.

| Causes of chronic cough | • Acute tracheobronchial infections including pertussis• Chronic infections: bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis• Airway problems: chronic bronchitis, osteoplastic tracheopathy, asthma, post-nasal drip• Pulmonary parenchymal diseases: diffuse interstitial fibrosis, emphysema, sarcoidosis• Tumors: lung cancer, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, benign airway tumors, mediastinal tumors• Foreign bodies in the airways• Irritation of external auditory meatus• Cardiovascular diseases: left ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary infarction, aortic aneurysm• Other diseases: gastroesophageal reflux or bronchoesophageal reflux, Zenker's diverticulum, achalasia, recurrent aspiration, endobronchial sutures• Drugs: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, covertine |

| Warning symptoms | Hemoptysis, snoring, significant production of sputum, systemic symptoms, gastroesophageal reflux complicated with weight loss, anemia, hematemesis, dysphagia, or no response to specific treatment, choking or vomiting, recurrent pneumonia, or abnormal chest X-ray |

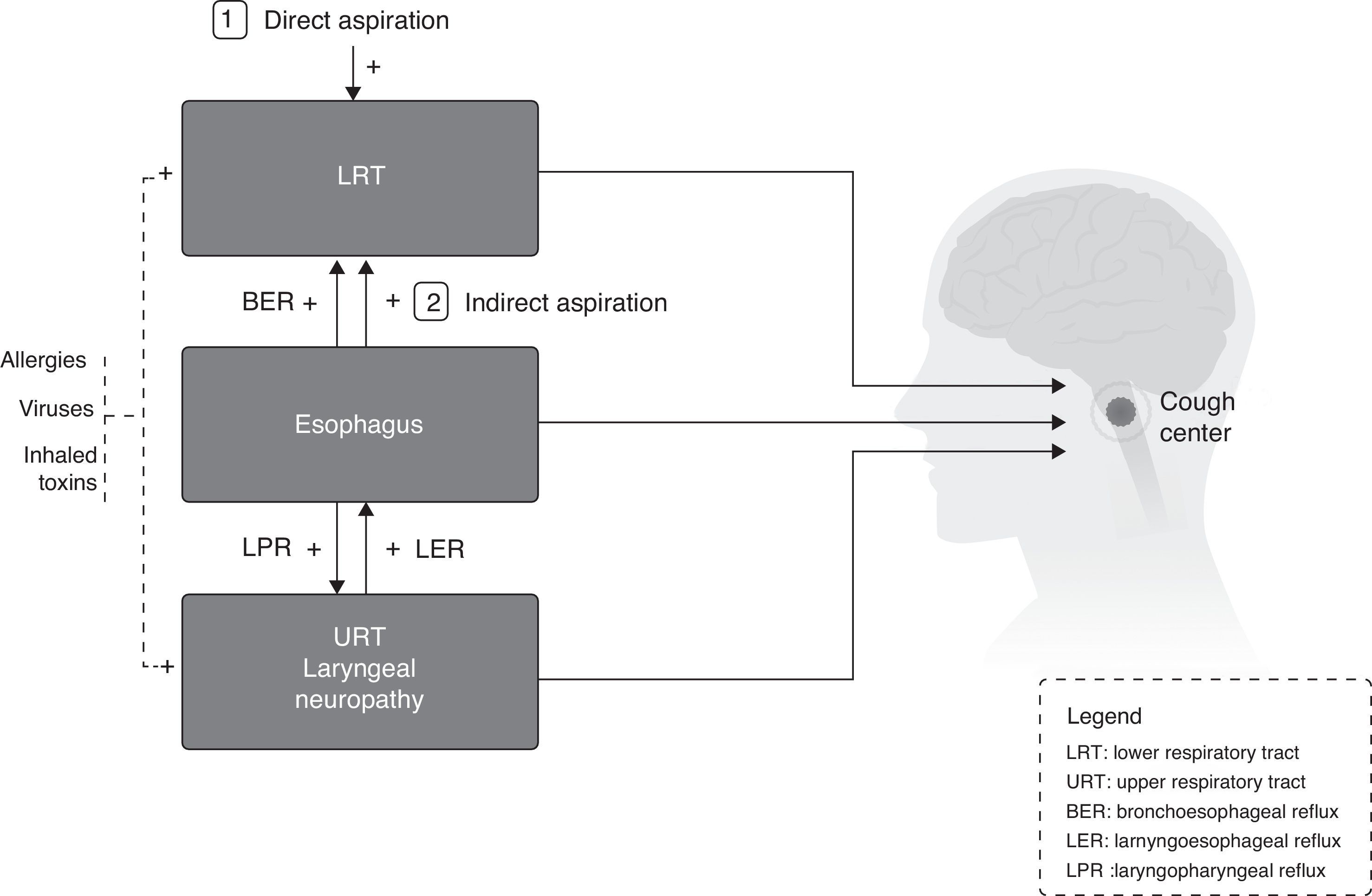

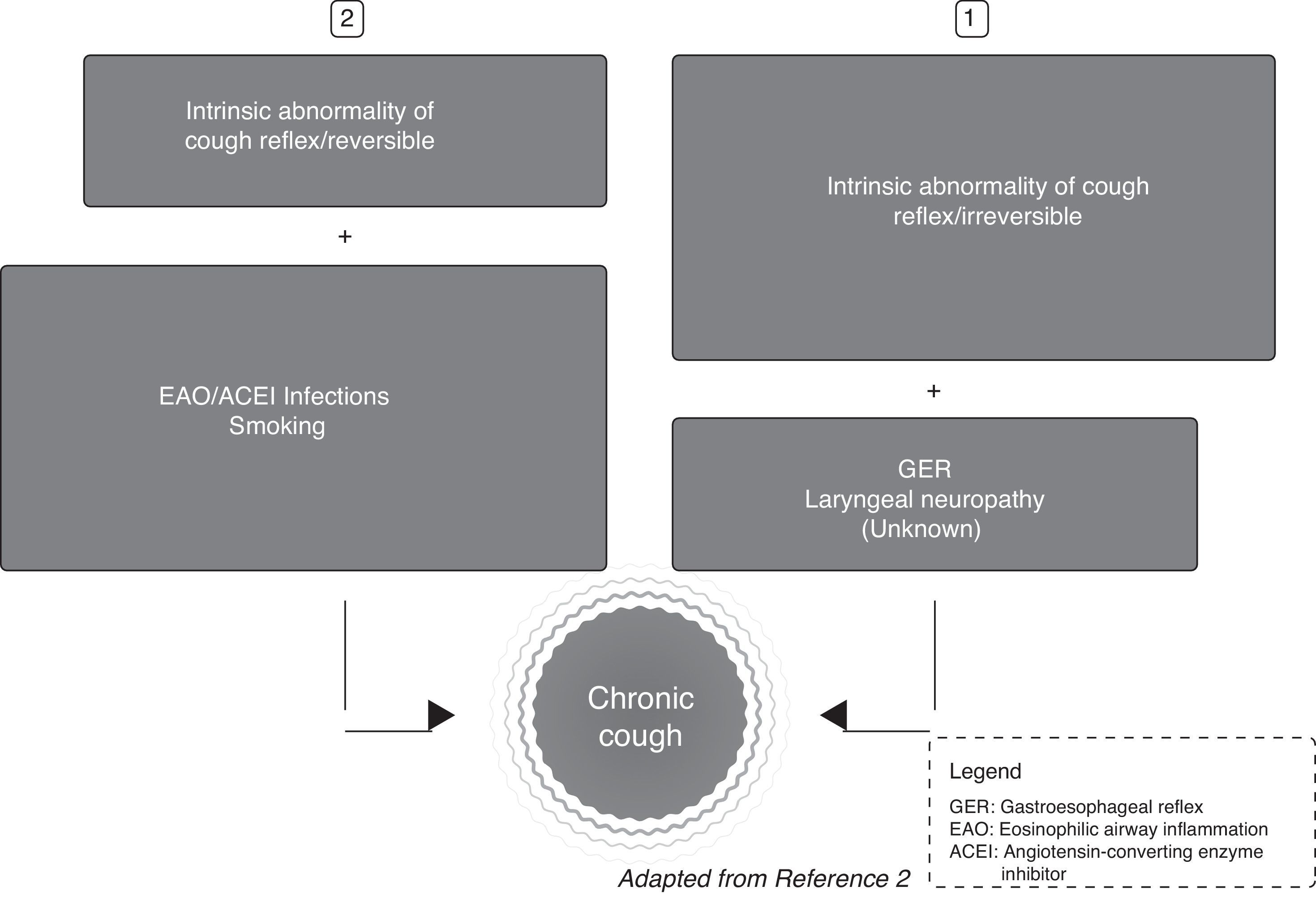

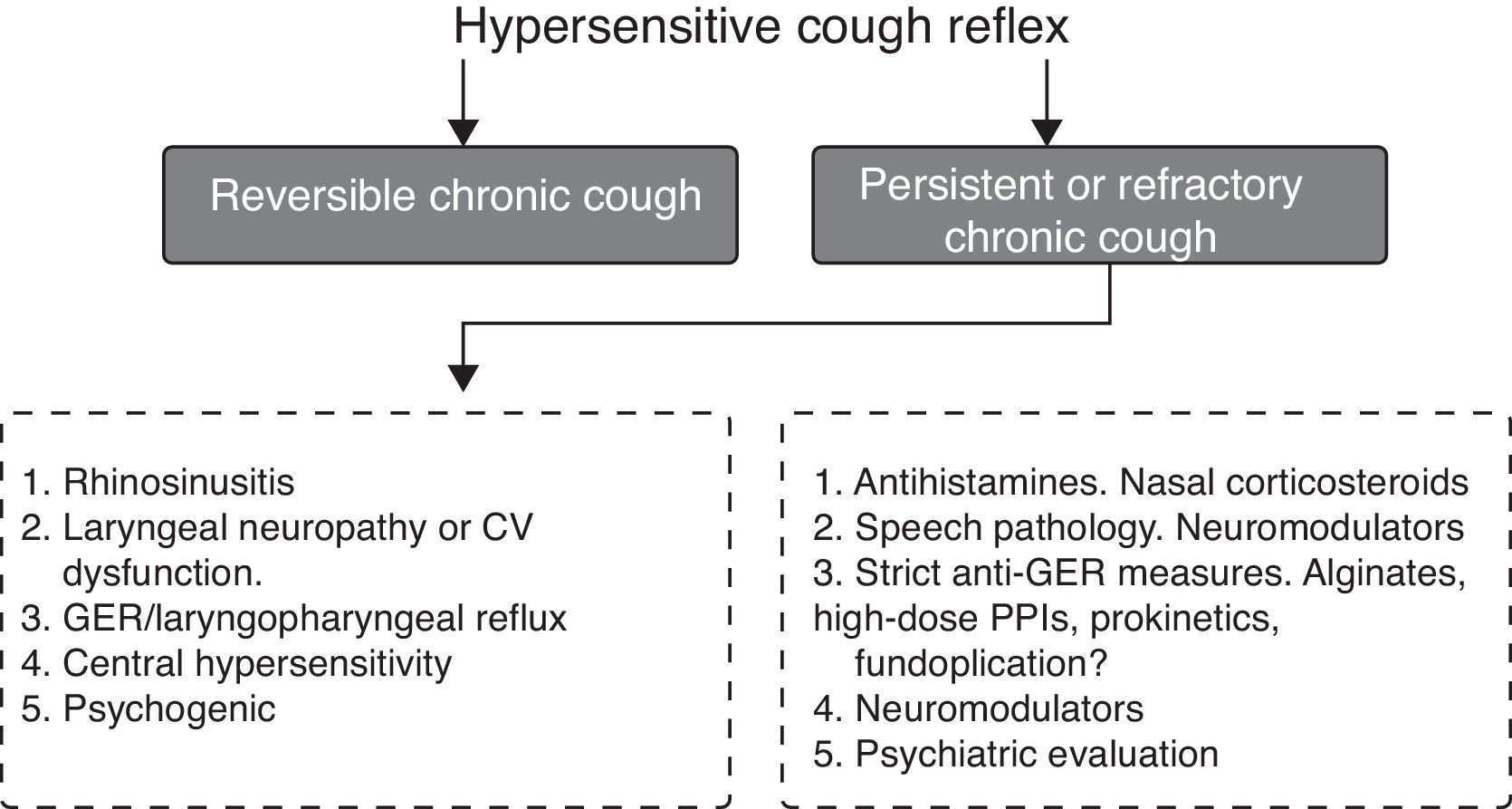

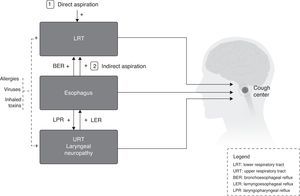

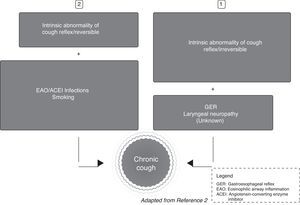

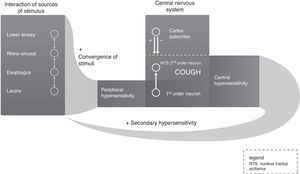

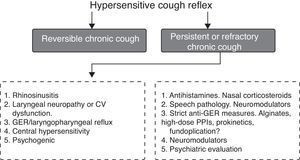

CC is reported by patients as either a single isolated symptom or one of several. Neurobiological mechanisms in chronic pain and in CC are similar,8 so the patient with chronic pain or CC responds more intensely to a painful stimulus or tussigenic stimulus of a specific magnitude than a healthy individual; this effect has been called hypertussia (similar to hyperalgesia). If the patient receives a stimulus that is not at all painful or tussigenic and responds excessively, the condition is called allotussia (or allodynia, in the case of pain).9 Hypertussia or allotussia are clinical conditions that are now grouped under the heading of “chronic cough hypersensitivity syndrome” (CCHS). The cough circuit is unquestionably complex, and may involve interaction between the different stimuli from the very start8 (Fig. 1). In short, the possible impact of CC on physiology means that the following must be taken into consideration when treating this condition: (a) cough neural pathways themselves may be affected, or (b) an aggravating factor that alters the cough reflex may need to be treated (Fig. 2).

The neurological mechanism of cough in humans originates from stimulation of 2 types of neuron terminals that converge in the cough center: unmyelinated C fibers and myelinated Aδ fibers.10,11 Most C fibers respond to a range of irritant stimuli of inflammatory origin, while Aδ fibers respond to mechanical and acid stimuli.12

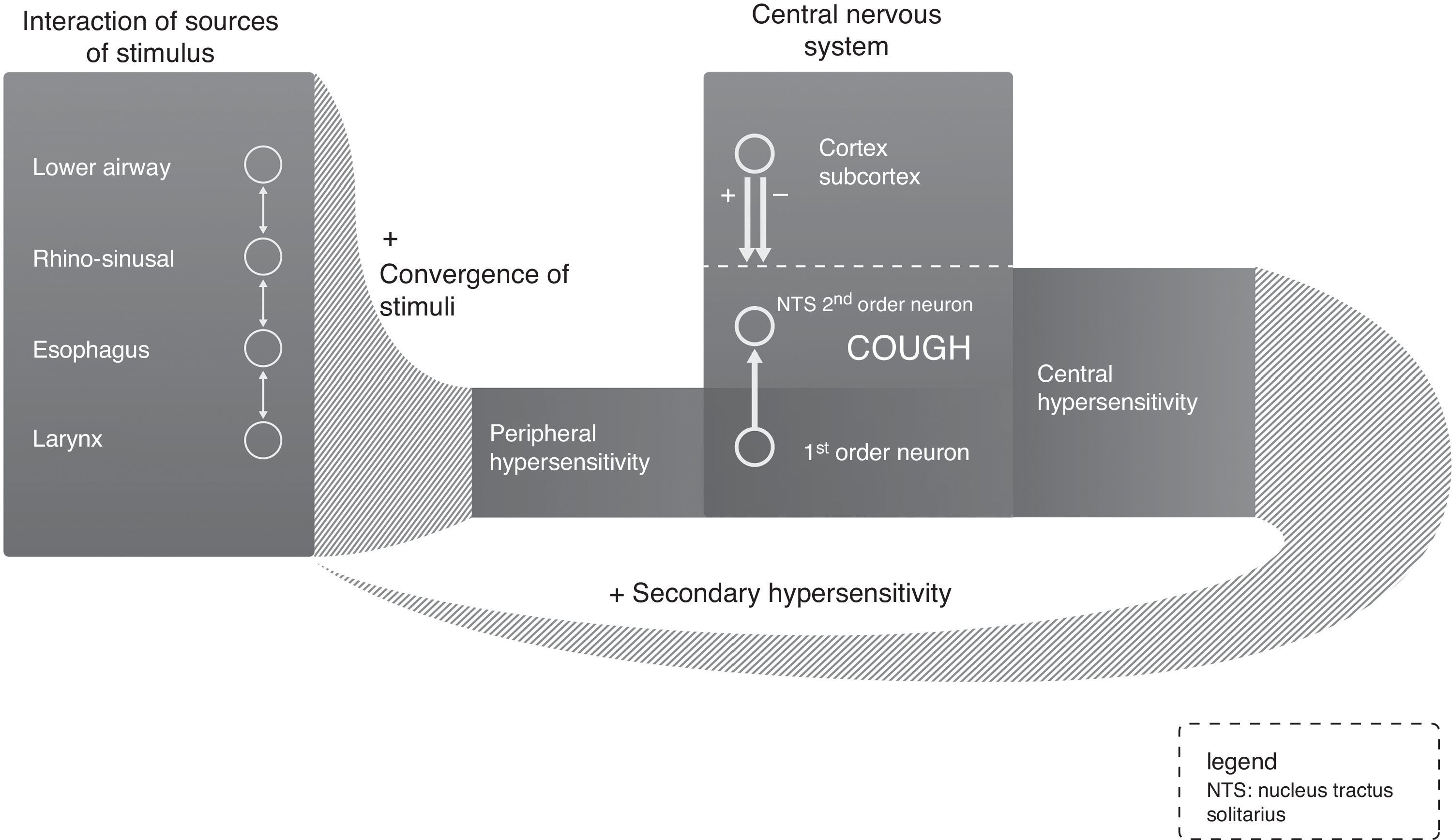

Excitability of the CNS cough center is increased by 3 mechanisms13: peripheral, central and secondary hypersensitivities (Fig. 3). In the case of central sensitization, paresthesia is often observed in the area of the larynx, as well as hypertussia or allotussia, indicating a neuropathic response.14 In the second mechanism, connections with the cough center via the emotional brain lead to participation of consciousness and the emotional status in the control of cough.

Furthermore, it is important to remember that the phenomenon of different converging peripheral stimuli can have a practical application, as suggested by the Australian cough guidelines of 2010, which recommend simultaneous triple therapy, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and speech pathology intervention for RCC15 (Strong recommendation/very low evidence). When central hypersensitivity has developed, a mechanism that is much more sensitive to mild peripheral stimuli is established, and this may be the cause of the phenomenon known as visceral hypersensitivity, also called secondary hypersensitivity (Fig. 3). The problem is that central hypersensitivity may decrease clinically, without changes being observed in the CC capsaicin challenge test due to peripheral hypersensitivity.16

Cough Study: Clinical Characterization and Laboratory DeterminationsPatients’ perception of cough may be expressed differently, depending on the causative pathology. In general, cough accompanying upper airway diseases or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) manifests as irritation in the throat. The “urge to cough” has been the subject of recent research which has located the origin of this impulse within the brain.17,18 Several standardized questionnaires have recently been developed to determine the characteristics of cough. These need further studies before they can be validated,19 and their utility in practice is still limited (Weak recommendation/low evidence). The intensity and frequency of cough have little diagnostic value, and these parameters are of most use when studying the therapeutic effect of antitussive agents. The intensity of cough can be determined with symptom questionnaires or quantified scales, mainly of the visual analog type (Weak recommendation/low evidence). The impact of cough on health-related quality of life is a useful parameter that can be measured objectively. To date, the most widely accepted tool is the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ).20 The importance of measuring the impact of cough on quality of life is high (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence).

The second aspect to consider is the study of the tussigenic reflex and its sensitivity with objective challenge techniques using inhaled substances. These methods have been described in recent guidelines published by the European Respiratory Society.21 Capsaicin acts directly on specific TRPV1 receptors. New ways of expressing results have been recently proposed, including the complete analysis of dose–response curve, measuring ED50 and Emax.22 Sensitivity and specificity of the capsaicin test in the differential diagnosis of CC and in healthy individuals are low.23,24 It is currently recommended for use in epidemiological studies or for determining the effect of drugs (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). Inhalation of mannitol in dry powder correlates well with the capsaicin test, but the sensitivity and specificity of the technique are similarly low (Strong recommendation/low evidence). Quantification of the fraction of nitric oxide in exhaled air (FeNO), when high (>30 or 38 parts per billion [ppb], depending on the author), predicts a favorable response to corticosteroid treatment of CC.25 Likewise, the quantification of eosinophils in sputum and peripheral blood can characterize a group of CC patients with eosinophilic inflammation of the airways who are potential responders to corticosteroid treatment26 (Strong recommendation, low quality of evidence).

Specific Causes of Chronic CoughThe physiopathological interpretation of CC has changed recently, and it is now understood as a unitary neurological response to stimuli received from distinct but interactive anatomical origins27,28 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence) (Fig. 1). Current thinking is that (a) CC is partially or totally resistant to specific treatment in up to 2/3 of patients,29 and (b) most individual carriers of the anatomical-diagnostic triad of conditions do not present CC.

New perspectives in the mechanism of the cough reflex suggest that in these patients, most symptoms are centered in the larynx.30 This has produced the concept of the “laryngeal hypersensitivity syndrome” (LHS) as a fundamental clinical basis for CC, particularly in its refractory form.31

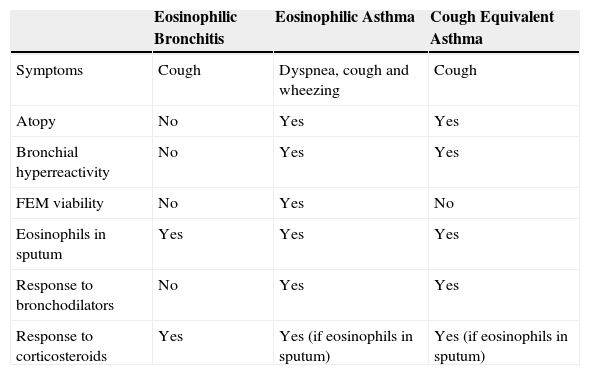

Chronic Cough and Lower Airway DiseasesIn prolonged or persistent bacterial bronchitis, extended treatment of over 2 weeks with antibiotics targeting the causative pathogen leads to complete resolution of CC32 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). It is now agreed that there are 2 asthma phenotypes: eosinophilic and neutrophilic asthma. It was reported recently that 75% of patients with neutrophilic asthma have moderate to severe CC33 (Weak recommendation/low evidence). Studies of eosinophilic airway inflammation measured by FeNO and eosinophils in sputum are highly specific and sensitive and predict good response to corticosteroids34 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). The diagnosis of asthma is defined as reversible bronchial obstruction, variable maximum expiratory flow and bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR), as determined by spirometry with bronchodilator testing, monitoring of maximum expiratory flow, or bronchial challenge testing (BCT) (Strong recommendation/high evidence). Asthma can be ruled out by a negative BCT, but if it is positive, the positive predictive value ranges between 60% and 80%35 (Strong recommendation/high evidence). BHR with no evidence of variable flow obstruction associated with CC suggests a diagnosis of cough-equivalent asthma or cough-variant asthma36; in this entity, antileukotrienes appear to be more effective than in conventional asthma37 (Strong recommendation/low evidence). A form of CC called eosinophilic bronchitis (EB), characterized by eosinophils in induced sputum, absence of BHR and good response to corticosteroids, was recently defined: prevalence is 7%–33%.38 Similarities and differences between these entities are summarized in Table 2. With respect to the recently described entity of neutrophilic asthma associated with CC and gastroesophageal reflux (GER), treatment with macrolides has been proposed, but the effect on CC has not been specified39 (Weak recommendation/low evidence). Similarly, treatment with the monoclonal antibody mepolizumab has shown success in eosinophilic asthma, although it failed to resolve the accompanying CC,40 suggesting that the inflammation may be mast cell-mediated.

Differential Diagnosis Between Various Diseases With Eosinophilic Inflammation of the Airways Associated With Chronic Cough.

| Eosinophilic Bronchitis | Eosinophilic Asthma | Cough Equivalent Asthma | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Cough | Dyspnea, cough and wheezing | Cough |

| Atopy | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bronchial hyperreactivity | No | Yes | Yes |

| FEM viability | No | Yes | No |

| Eosinophils in sputum | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Response to bronchodilators | No | Yes | Yes |

| Response to corticosteroids | Yes | Yes (if eosinophils in sputum) | Yes (if eosinophils in sputum) |

Adapted from Desai and Brightling (Cough: Asthma, eosinophilic diseases. Otorlaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43:123) and Morice (Epidemiology of cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:253–259). Adapted from Desai and Brightling.86

Laryngeal conditions have usually been considered in the diagnostic triad as chronic upper airway cough syndrome (CUACS), formerly known as post-nasal drip; nevertheless, in view of the high rate of laryngeal symptoms in CC, LHS has recently been associated with laryngeal neuropathy.

There are 5 upper airway conditions that may present with CC: allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis in the adult, obstructive sleep apnea, vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), and extra-esophageal manifestation of ERG or LPR.

Allergic rhinitis: this is diagnosed from signs and symptoms of nasal inflammation and the identification of specific allergens in skin prick testing or RAST. This condition should be managed according to the recommendations of the recent guidelines.41Chronic rhinosinusitis: treatment consists of irrigation of the nostrils with saline solution, oral corticosteroids for at least 1 month, and oral antibiotics for up to 3 months, in the case of purulent sinusitis (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence).

Obstructive sleep apnea (see section on “Chronic cough and sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome”).

Vocal cord dysfunction: VCD is diagnosed from episodic narrowing of the vocal cords during inspiration producing dyspnea on inspiration and CC.42 CC occurs in more than 50% of adults with this condition. VCD is diagnosed by the observation of glottic narrowing on laryngoscopy or by a fall of more than 25% in inspiratory flow during the serum saline challenge maneuver.43 Management consists of the treatment of associated comorbidities such as asthma, rhinosinusitis, GER or the use of ACEI (Weak recommendation/low evidence), and the application of speech pathology intervention43 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence).

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR): see below.

Chronic Cough and Gastroesophageal Reflux. Laryngopharyngeal ReflexGastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been associated with a variety of extra-esophageal manifestations, including CC.44

Relationship Between Chronic Cough and Gastroesophageal RefluxIn a study performed in a series of CC patients exploring the temporal association between episodes of cough, recorded by acoustic analysis, and episodes of GER, recorded by outpatient esophageal pH impedance, Smith et al.45 found that cough could appear before or after (50% of the time) episodes of GER. Wu et al.46 showed that distal esophageal acid infusion increases cough reflex sensitivity in asthmatic patients but not in normal subjects. Finally, it has been proposed recently that CC may be caused by the harmful effects of GER products on the larynx, causing laryngeal neuropathy,47,48 suggesting that CC may be a neuropathic disease caused by GER.

Diagnosis of Chronic Cough Associated With RefluxThe most useful test for corroborating the GER-cough association is 24-h outpatient recording of both pH and esophageal impedances. This technique can detect episodes of both liquid and aerosolized acid (pH<4), mildly acid (pH 4–7) and alkaline (pH>7) GER.45

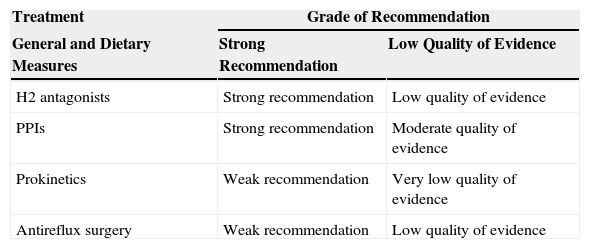

Treatment of Chronic Cough Associated With Gastroesophageal RefluxAnti-reflux treatment for CT is specified in Table 3. Two systematic reviews have been published on this topic.49,50 In adults, there is insufficient evidence to conclude definitively that PPIs are beneficial in GER-associated cough. However, the presence of abnormal GER or the temporal association of GER with cough are factors for improved response to treatment.50 In patients with no signs of GER, a 2-month treatment may be justified if the following criteria are present: non-smoker, no use of ACEI, normal chest X-ray, no asthma, no post-nasal drip, and no non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis.51

Grades of Recommendation/Evidence of Antireflux Treatment in Patients With Chronic Cough.

| Treatment | Grade of Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|

| General and Dietary Measures | Strong Recommendation | Low Quality of Evidence |

| H2 antagonists | Strong recommendation | Low quality of evidence |

| PPIs | Strong recommendation | Moderate quality of evidence |

| Prokinetics | Weak recommendation | Very low quality of evidence |

| Antireflux surgery | Weak recommendation | Low quality of evidence |

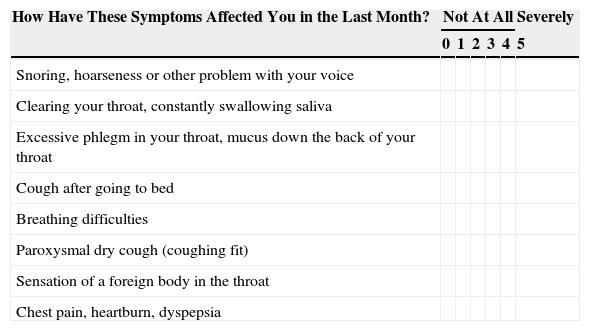

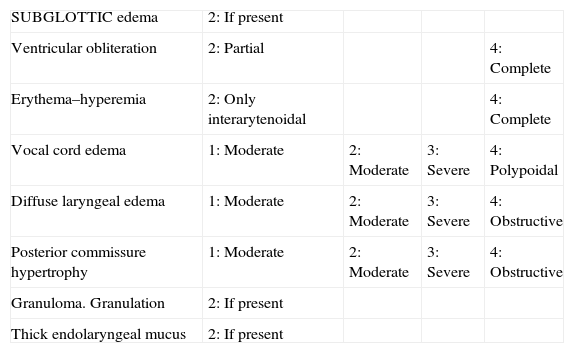

Laryngopharyngeal reflux: LPR is defined as GER reaching the laryngopharyngeal region. Diagnosis is confirmed by: (a) symptoms of extra-esophageal reflux, or (b) laryngeal endoscopy. Validated indices are available – for the first, the “Reflux Symptoms Index”, and for the second, the “Reflux Findings Score”52; both have a qualification of Weak recommendation/moderate evidence (Tables 4 and 5).

Laryngeal Reflux Symptom Index.

| How Have These Symptoms Affected You in the Last Month? | Not At All | Severely | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Snoring, hoarseness or other problem with your voice | ||||||

| Clearing your throat, constantly swallowing saliva | ||||||

| Excessive phlegm in your throat, mucus down the back of your throat | ||||||

| Cough after going to bed | ||||||

| Breathing difficulties | ||||||

| Paroxysmal dry cough (coughing fit) | ||||||

| Sensation of a foreign body in the throat | ||||||

| Chest pain, heartburn, dyspepsia | ||||||

More than 13 points suggest laryngopharyngeal reflux.

Index of Endoscopic Signs of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux.

| SUBGLOTTIC edema | 2: If present | |||

| Ventricular obliteration | 2: Partial | 4: Complete | ||

| Erythema–hyperemia | 2: Only interarytenoidal | 4: Complete | ||

| Vocal cord edema | 1: Moderate | 2: Moderate | 3: Severe | 4: Polypoidal |

| Diffuse laryngeal edema | 1: Moderate | 2: Moderate | 3: Severe | 4: Obstructive |

| Posterior commissure hypertrophy | 1: Moderate | 2: Moderate | 3: Severe | 4: Obstructive |

| Granuloma. Granulation | 2: If present | |||

| Thick endolaryngeal mucus | 2: If present |

More than 6 points suggests laryngopharyngeal reflux.

The treatment of GER complicated by LPR is similar to that described for GER associated with CC: high doses of PPIs (20 or 40mg every 12h), for at least 2 months. If there is no response after this time, PPIs should be discontinued (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence), but if the patient shows improvement of CC, administration of PPIs should be reduced to once daily, after which the minimum dose required to maintain sufficient acid suppression should be introduced. If, on the other hand, the patient does not improve and CC due to GER is still suspected, a pH-metry/impedance test with additional manometry should be performed (Weak recommendation/high evidence). If suspected LPR is confirmed but treatment with PPIs fails, some authors have reported improvement with GABA inhibitors, such as baclofen, at escalating doses of up to 30mg/day,53 or the addition of alginates (e.g., Gaviscon®).54 Fundoplication for the treatment of LPR with CC would require a major GER complication or risk of massive aspiration (Weak recommendation/low evidence) (Table 3). Good outcomes in tussigenic hypersensitivity caused by concomitant laryngeal sensory neuropathy and LPR have been demonstrated with neuromodulating drugs.55

If interaction between LPR and laryngeal neuropathy is clinically suspected, there are 2 complementary approaches: changes in patient care and diet, and speech pathology interventions. Raising the head of the bed, adopting a left lateral decubitus position, and weight loss have been shown to improve the total time that esophageal pH is less than 4 (Strong recommendation/low evidence).56 A recent study in GER found that a period of less than 3h between eating dinner and going to bed was significantly related with GER relapse.57 Speech pathology intervention reduces response to capsaicin-induced cough reflex.43

Chronic Cough and Sleep Apnea–Hypopnea SyndromeIn both healthy individuals and patients with CC, cough is generally more frequent during the day. In some sleep-related diseases, such as sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (SAHS), the situation is different.58 The prevalence of CC in this population can be as high as 33%–39%.59 In our experience,60 42% of patients with SAHS reported CC, of whom 31% had high GER symptom scores. With regard to the effects of CPAP on cough, a significant improvement was found, with resolution of cough in 67%. Similarly, when the prevalence of SAHS was analyzed in patients with CC,61 44% were found to have criteria for SAHS. To summarize, CC is frequently associated with SAHS, particularly in patients with associated GER (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). CPAP treatment may be indicated for the treatment of CC (Weak recommendation/moderate evidence), although more research is required.

Miscellaneous: Post-Infectious Chronic Cough, Psychogenic Chronic Cough. Other Entities Involving Chronic CoughPost-Infectious Chronic CoughNumerous publications suggest that most coughs related with upper respiratory tract infections resolve within a period of up to 3 weeks. Nevertheless, cough may persist longer in a small proportion of adult patients. Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of pertussis, is increasingly recognized as the cause of CC. Diagnosis is established from culture and polymerase change reaction (PCR) analysis of upper respiratory tract samples (Weak recommendation/low evidence). Antibiotic treatment with azithromycin should be considered in suspected cases, although this will only prevent transmission, rather than improve symptoms (Strong recommendation/high evidence).62

Psychogenic Chronic CoughIn a recent review of psychogenic cough, 223 patients were identified from a total of 18 uncontrolled studies,63 96% of whom were children and teenagers: 95% of patients did not have cough during sleep. Hypnosis is effective in resolving cough in 78% of patients. The large majority of improvements were seen in the pediatric population. To conclude, there is low quality evidence to support a specific strategy that defines and treats psychogenic cough, habit cough and tic cough. In general, the diagnosis of psychogenic cough should be made after ruling out more common causes of CC, and when CC improves with behavioral modification and/or psychiatric therapy.64

Other Types of Chronic CoughCC in occupational exposure has been described in glass workers and in environments with high concentrations of dust and organic material in the air.65 A sensory neuropathy syndrome with autonomous nervous system dysfunction, cough and GER66 indicates genetic dysfunction in the neurological network of the digestive tract. CT due to irritation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (Arnold's nerve) may occur rarely, as may CC associated with osteoplastic tracheobronchopathy. Other rare cases of CC must be systematically determined according to Table 1.

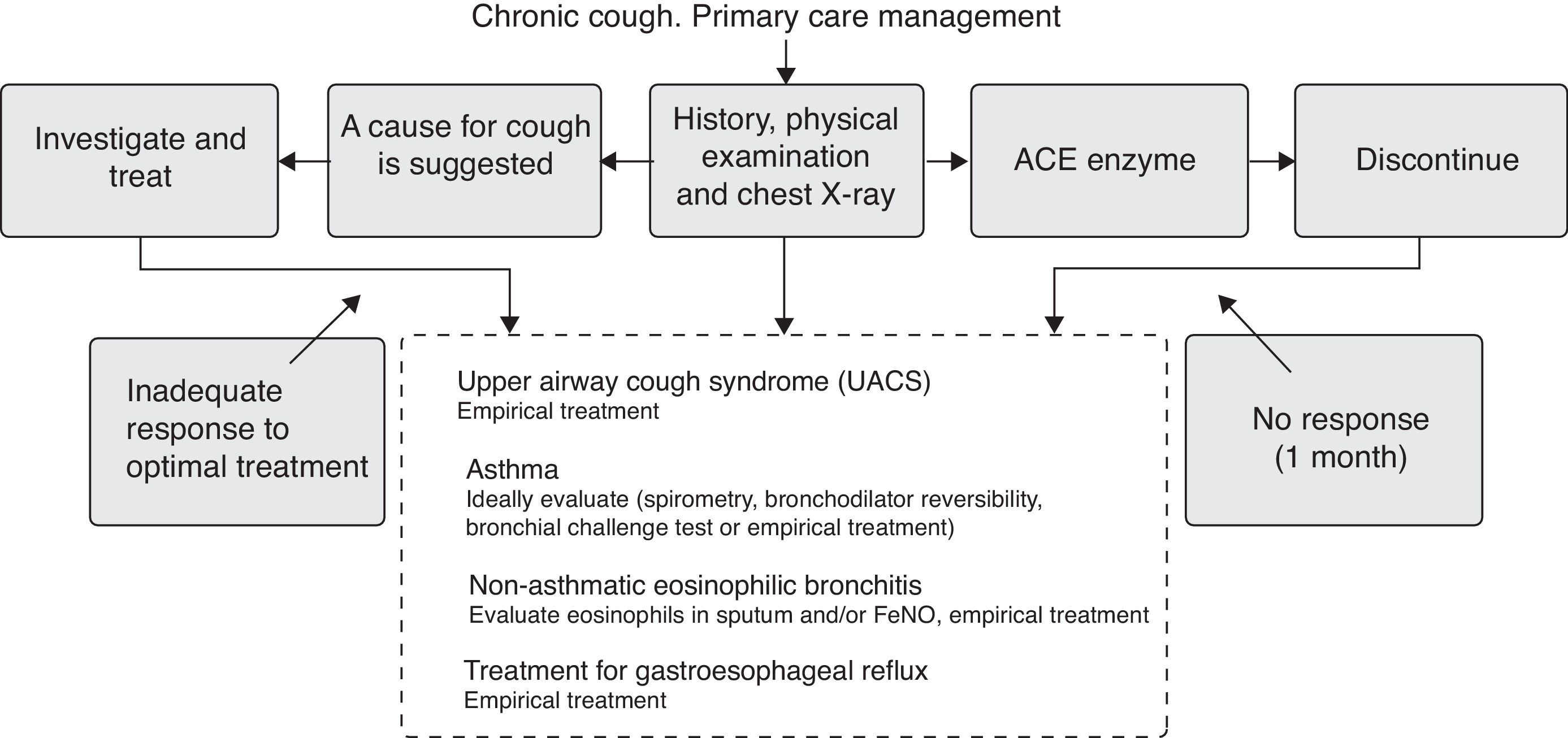

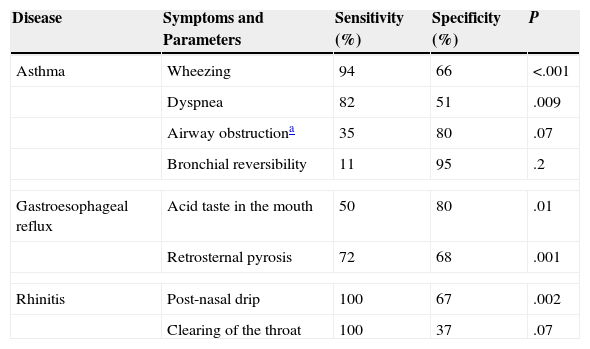

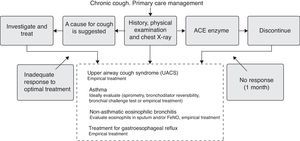

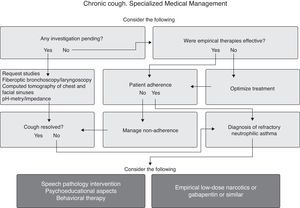

Management of Chronic Cough in the Different Levels of Medical CareChronic Cough in Primary CareMost patients with CC who present in primary care (PC) can be diagnosed by following the algorithm presented in Fig. 4 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). In 1 study, only 31% of the patients had any radiological changes that might guide diagnosis.67 Protocolized empirical and sequential treatment has been shown to be cost-effective.68,69 In a recent study of 112 patients with CC,69 sensitivity and specificity of symptoms for 3 of the diseases most frequently associated with CC were determined, as shown in Table 6.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Cough.

| Disease | Symptoms and Parameters | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Wheezing | 94 | 66 | <.001 |

| Dyspnea | 82 | 51 | .009 | |

| Airway obstructiona | 35 | 80 | .07 | |

| Bronchial reversibility | 11 | 95 | .2 | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | Acid taste in the mouth | 50 | 80 | .01 |

| Retrosternal pyrosis | 72 | 68 | .001 | |

| Rhinitis | Post-nasal drip | 100 | 67 | .002 |

| Clearing of the throat | 100 | 37 | .07 | |

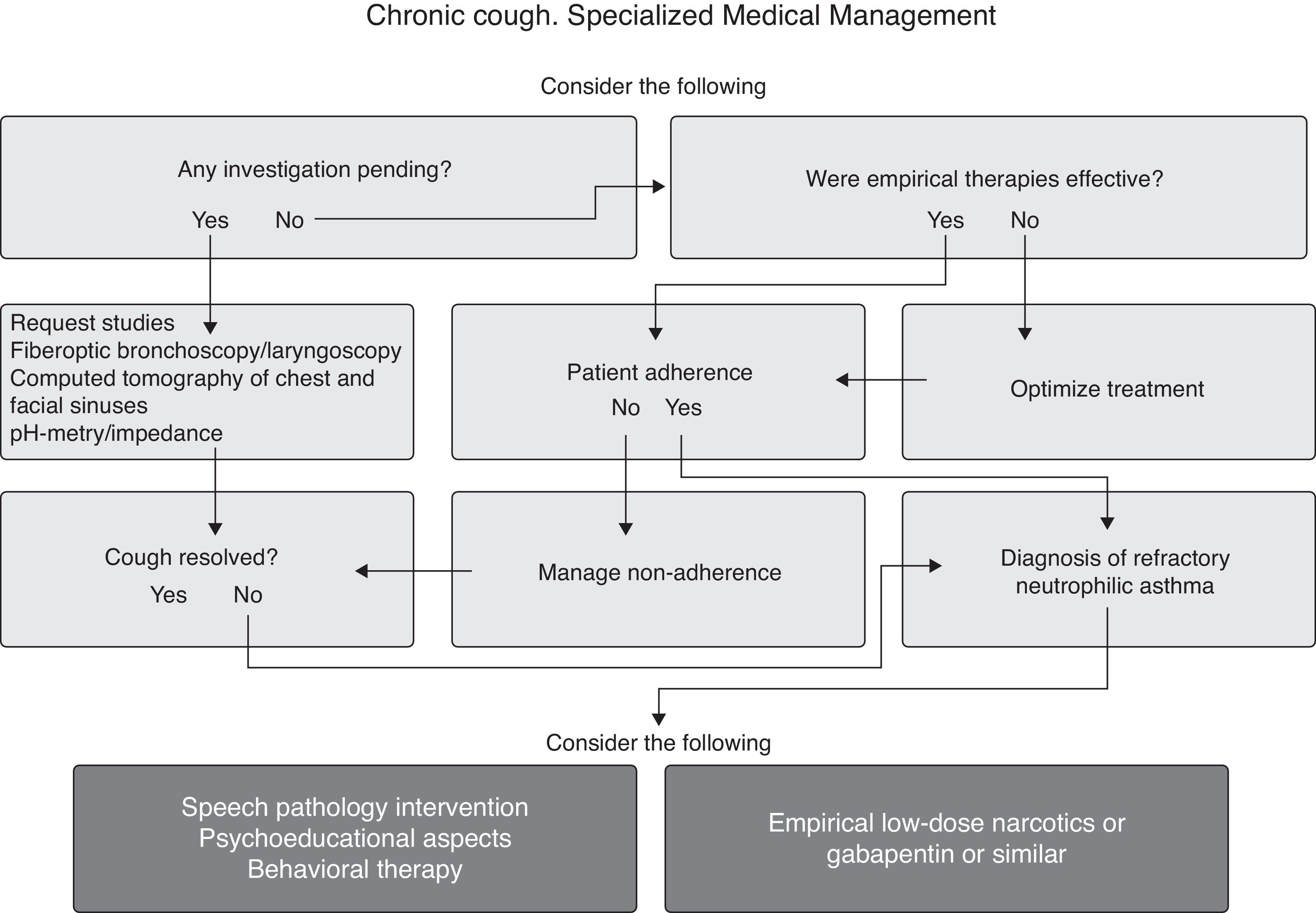

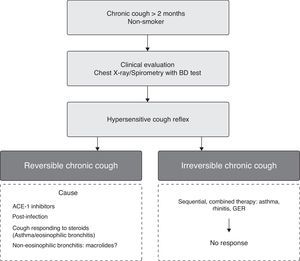

Algorithms for the management of patients with CC referred from PC to a higher level of medical care are given in Figs. 5 and 6. After ruling out neutrophilic asthma in the CC patient, treatment alternatives are neuromodulators, basically gabapentin (300–1800mg/day) and amitriptyline (10–20mg/day), and speech pathology intervention. The recommendation for both options is strong, while evidence remains weak (Fig. 7).

Chronic Cough in Pediatric PatientsThe American and Australian-New Zealand guidelines define CC as cough lasting more than 4 weeks,70 while the British guidelines71 set it at more than 8 weeks. According to several epidemiological studies, causes of CC in the child vary depending on age (Strong recommendation/high evidence). In schoolchildren, the most common causes are asthma (27%), cough-equivalent asthma (15.5%) and GER (10%). After adolescence, causes for CT are considered the same as in adults.

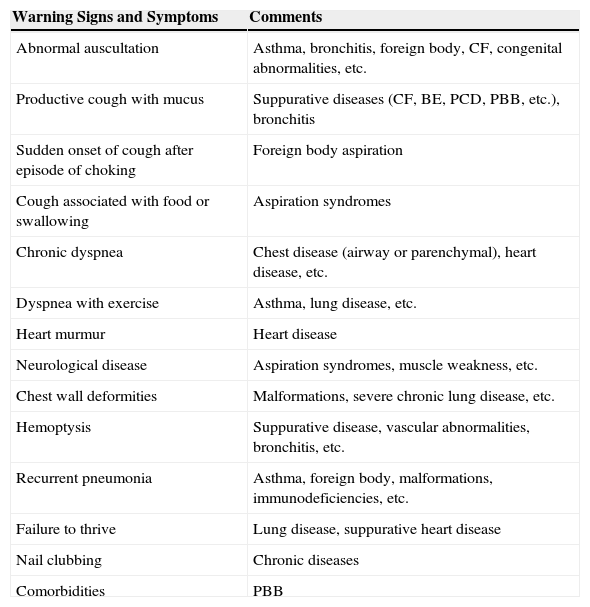

Diagnostic Evaluation of Chronic Cough in ChildrenClinical history, symptoms and warning signs (Table 7) and the physical examination and initial diagnostic tests are similar to those proposed for adults.

Warning Signs and Symptoms in Children With Chronic Cough.

| Warning Signs and Symptoms | Comments |

|---|---|

| Abnormal auscultation | Asthma, bronchitis, foreign body, CF, congenital abnormalities, etc. |

| Productive cough with mucus | Suppurative diseases (CF, BE, PCD, PBB, etc.), bronchitis |

| Sudden onset of cough after episode of choking | Foreign body aspiration |

| Cough associated with food or swallowing | Aspiration syndromes |

| Chronic dyspnea | Chest disease (airway or parenchymal), heart disease, etc. |

| Dyspnea with exercise | Asthma, lung disease, etc. |

| Heart murmur | Heart disease |

| Neurological disease | Aspiration syndromes, muscle weakness, etc. |

| Chest wall deformities | Malformations, severe chronic lung disease, etc. |

| Hemoptysis | Suppurative disease, vascular abnormalities, bronchitis, etc. |

| Recurrent pneumonia | Asthma, foreign body, malformations, immunodeficiencies, etc. |

| Failure to thrive | Lung disease, suppurative heart disease |

| Nail clubbing | Chronic diseases |

| Comorbidities | PBB |

BE: bronchiectasis; CF: cystic fibrosis; PBB: persistent bacterial bronchitis; PCD; primary ciliary dyskinesia.

The aim of CC treatment must be to eliminate the causative agent.70,71 If non-specific CC is predominantly dry, treatment with medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids for 2–12 weeks should be attempted, but withdrawn in the absence of response.72 In cases of non-specific productive CC, an initial 2 or 3-week course of antibiotics should be evaluated73 (Strong recommendation/high evidence). Central-acting antitussives are not indicated (Strong recommendation/high evidence).

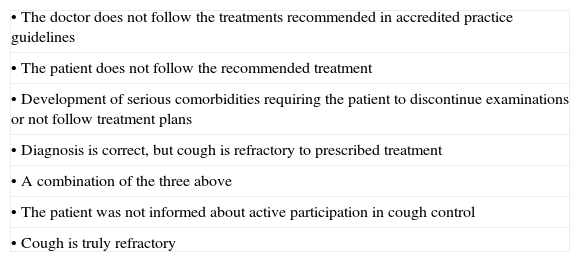

Problems and Perspectives in Chronic CoughChronic Refractory Cough and New TreatmentsIt is currently assumed that if partial control of cough can be achieved, this may be sufficient, since it is difficult to eradicate completely, except in some cases (Fig. 5). Unsatisfactory treatment in CC may be due to several causes74 (Table 8). In RCC, treatment possibilities must first be optimized (Fig. 6), and then 2 aspects should be given special attention: (a) LHS, and (b) central hypersensitivity75 (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence). Antitussive treatments should be used for “urge-to-cough”, but designed to avoid modification of the protective reflex cough. The available evidence suggests that nebulized lidocaine is an option for second-line treatment.76

Causes of Unexplained Cough in Adults.

| • The doctor does not follow the treatments recommended in accredited practice guidelines |

| • The patient does not follow the recommended treatment |

| • Development of serious comorbidities requiring the patient to discontinue examinations or not follow treatment plans |

| • Diagnosis is correct, but cough is refractory to prescribed treatment |

| • A combination of the three above |

| • The patient was not informed about active participation in cough control |

| • Cough is truly refractory |

Adapted from Irwin.74

In the second case, central hypersensitivity and treatment in CC, there is growing interest in the use of gabapentin in RCC, with positive responses in around 60% of patients (Strong recommendation/moderate evidence).77 Neuromodulator therapy is being proposed as the future in the treatment of central hypersensitivity.78 Other similar agents that have been studied in small, observational studies include pregabalin, amitriptyline, and baclofen. Amitriptyline or low-dose morphine have shown subjective improvement in the LCQ (Weak recommendation/moderate evidence).79

The efficacy of over-the-counter cough suppressants on CC has not been demonstrated.80 A recent review of dextromethorphan found a modest decrease in cough severity and frequency when compared to placebo.81 Codeine has shown no improvement in capsaicin-induced cough reflex testing.82 Its use in CC that does not respond to non-narcotic antitussives is currently recommended (Weak recommendation/low evidence).

Drugs for reducing peripheral hypersensitivity focusing on TRP receptor blockade have recently been evaluated.83 Inhaled tiotropium has recently been seen in laboratory animals to inhibit TRPV1 receptors.84 Another promising agent in the treatment of CC is AF-219, a receptor antagonist that acts against the purinergic receptor P2X3, and also against peripheral C fibers,85 and is effective in reducing CC frequency.

Please cite this article as: Pacheco A, de Diego A, Domingo C, Lamas A, Gutierrez R, Naberan K, et al. Tos crónica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:579–589.