At the end of the nineteenth century, foreign body (FB) aspiration had a mortality rate of 50%, but this has gradually fallen since the first endoscopic extraction performed by Gustav Killian. Modifications of the extraction technique followed, and today, flexible bronchoscopy is one of the most widely used methods in these cases. We present the case of a 67-year-old man diagnosed with aspiration of a dental drill bit used for dental implants.

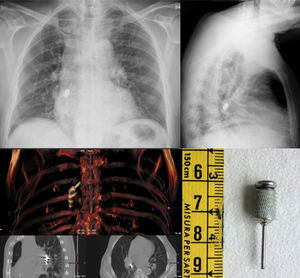

The patient came to the Emergency Department from a dental appointment one hour earlier, during which a drill bit had accidentally fallen into his oral cavity while he was undergoing root canal treatment, and disappeared; the dentist believed that the patient had swallowed it, and referred him to our hospital. The patient was asymptomatic on arrival. Chest X-ray and computed axial tomography (CT) (Fig. 1) revealed the drill bit in the bronchus intermedius, with no associated complications. Oral bronchoscopy was performed under sedation, and the bit was removed en bloc using crocodile forceps (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged 24h later.

The first published case of endoscopic extraction occurred on 30th March 1897, when a 63-year-old German farmer experienced dyspnea, cough and hemoptysis after aspirating a pork bone (11mm long and 3mm wide). Using a modified Mikulicz-Rosenheim esophagoscope (a rigid tube illuminated with a head mirror) and rigid forceps, Gustav Killian managed to remove the splinter from the right main bronchus.1

FB aspiration is most common in males aged between 1 and 2-years,2 with a mortality of 7% in children <4 years. The incidence in adults is <0.4%,3 mostly in the geriatric population, or in association with neurological diseases, alcohol or drug abuse, traumatic intubation, mental retardation, dental treatment and tracheotomy patients. The type of FB depends on the age: in children, up to 55% are of vegetable origin (peanuts and seeds2); in adults, Blanco et al. reported 32 cases of bronchoaspiration out of 9781 bronchoscopies performed, 78% of which were of inorganic material, followed by dental material.3

Only one case involving the same dental object with characteristics and results similar to ours has been published.4

Symptoms, when present, are usually: intractable cough, dyspnea or repeated infections. Abnormal findings on chest X-ray include atelectasia, infiltrates or signs of hyperinflation, although results are normal in more than 40% of patients.3

Bronchoscopy is the technique of choice; the most common location is the bronchus intermedius, and foreign bodies are observed in routine bronchoscopies in up to 9% of patients.5 The extraction technique varies from non-bronchoscopic techniques (in small, movable objects like dried fruits or seeds) where positioning maneuvers and/or the use of systemic steroids to reduce the edema and facilitate expectoration may suffice,5 to endoscopic techniques or thoracotomies. The endoscopic route will avoid distal displacement of the FB, using a Fogarty catheter or balloon prior to its extraction.5 Although flexible bronchoscopy is recommended in most cases,3 rigid bronchoscopy is the technique of choice in children <12 years and some adults, depending on the FB and patient.2

Please cite this article as: Gómez López A, García Luján R, de Miguel Poch E. Broncoaspiración de cuerpos extraños. Caso clínico y revisión. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:358–359.