Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive form of fibrosing interstitial pneumonia, characterized by progressive symptomatic and functional worsening, with no clearly determined etiological profile. IPF is associated with passive smoking, gastroesophageal reflux, chronic viral infections, pulmonary emphysema, and lung cancer.1,2 Lung cancer is more prevalent in these patients (as documented by clinical monitoring and post-mortem reports), with a cumulative 3-year incidence of 82%. As such, IPF is considered an independent risk factor for the development of lung cancer (LC), correlating with time accumulated since diagnosis.3–7

We are therefore looking at a progressive disease with a poor prognosis and a higher incidence of LC, in which clinical management and therapeutic decision-making are a challenge.

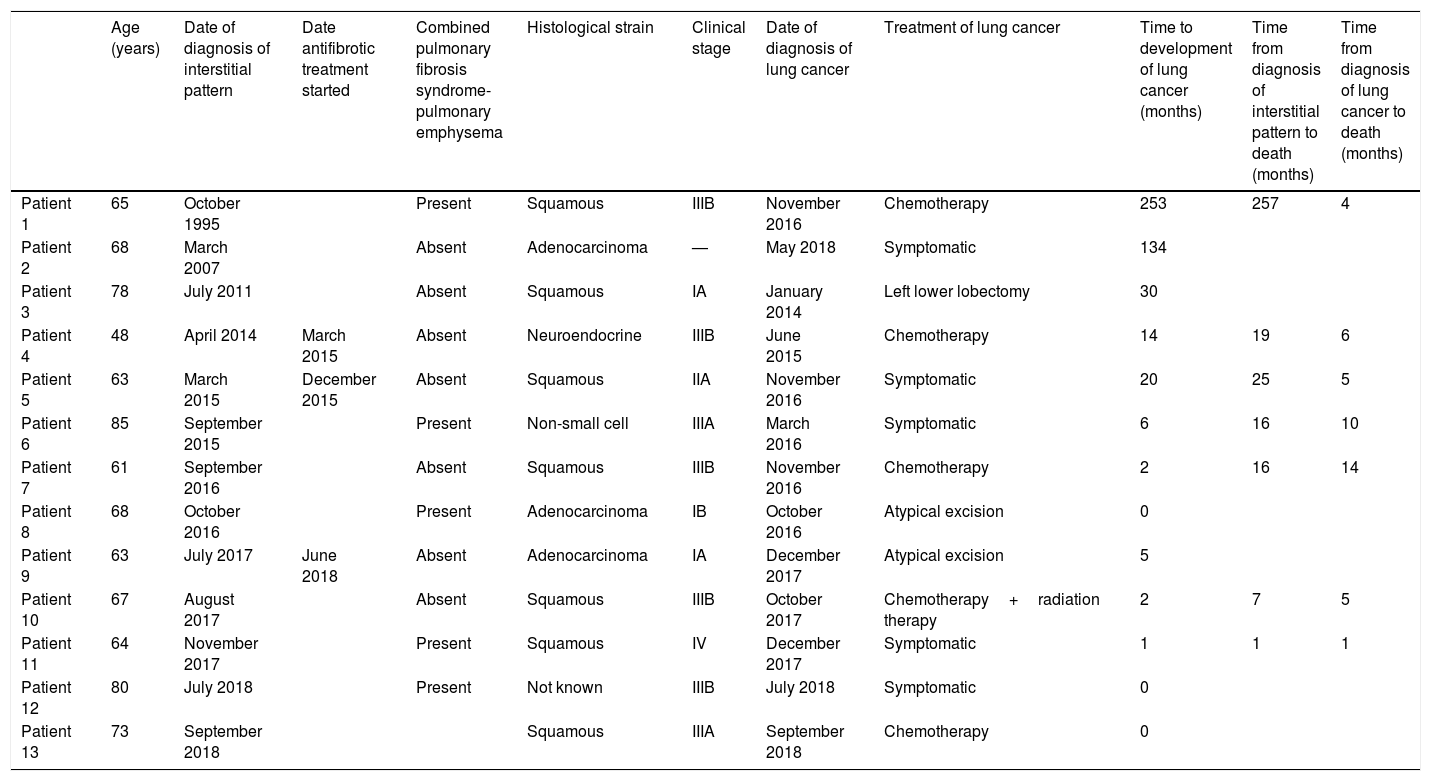

We report a series of 13 cases from our hospital (Table 1), included between January 2014 and December 2018. In total, 93 % of the patients were male (n=12), with a mean age of 67.9 years, and, interestingly, all participants had a history of smoking (current or former). Detailed anamnesis revealed a family history of LC in 30 % of cases, and one of the patients reported a family cluster of IPF. In total, 38 % (n=5) met radiological criteria for combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE).

Detailed characteristics of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer.

| Age (years) | Date of diagnosis of interstitial pattern | Date antifibrotic treatment started | Combined pulmonary fibrosis syndrome-pulmonary emphysema | Histological strain | Clinical stage | Date of diagnosis of lung cancer | Treatment of lung cancer | Time to development of lung cancer (months) | Time from diagnosis of interstitial pattern to death (months) | Time from diagnosis of lung cancer to death (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 65 | October 1995 | Present | Squamous | IIIB | November 2016 | Chemotherapy | 253 | 257 | 4 | |

| Patient 2 | 68 | March 2007 | Absent | Adenocarcinoma | — | May 2018 | Symptomatic | 134 | |||

| Patient 3 | 78 | July 2011 | Absent | Squamous | IA | January 2014 | Left lower lobectomy | 30 | |||

| Patient 4 | 48 | April 2014 | March 2015 | Absent | Neuroendocrine | IIIB | June 2015 | Chemotherapy | 14 | 19 | 6 |

| Patient 5 | 63 | March 2015 | December 2015 | Absent | Squamous | IIA | November 2016 | Symptomatic | 20 | 25 | 5 |

| Patient 6 | 85 | September 2015 | Present | Non-small cell | IIIA | March 2016 | Symptomatic | 6 | 16 | 10 | |

| Patient 7 | 61 | September 2016 | Absent | Squamous | IIIB | November 2016 | Chemotherapy | 2 | 16 | 14 | |

| Patient 8 | 68 | October 2016 | Present | Adenocarcinoma | IB | October 2016 | Atypical excision | 0 | |||

| Patient 9 | 63 | July 2017 | June 2018 | Absent | Adenocarcinoma | IA | December 2017 | Atypical excision | 5 | ||

| Patient 10 | 67 | August 2017 | Absent | Squamous | IIIB | October 2017 | Chemotherapy+radiation therapy | 2 | 7 | 5 | |

| Patient 11 | 64 | November 2017 | Present | Squamous | IV | December 2017 | Symptomatic | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Patient 12 | 80 | July 2018 | Present | Not known | IIIB | July 2018 | Symptomatic | 0 | |||

| Patient 13 | 73 | September 2018 | Squamous | IIIA | September 2018 | Chemotherapy | 0 |

In our series, the most common tumor lineage was squamous (n=9), followed by adenocarcinoma (n=3) at rates similar to those reported in the literature.4,5,8 However, no statistical association was found between the higher incidence of peripheral lesions and their location in lower lobes, as previously described by Kwak et al.9 (p>0.05). IPF was diagnosed using clinical/radiological criteria10 (n=8) or lung histology showing a pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (n=7).

The diagnosis of LC was synchronous with IPF and incidental in 3 cases; this figure was much lower than that reported by Huddad and Massaro.5 In the remaining patients (n=10), the presence of lung cancer was detected after a mean follow-up of 18.2 months (SD: 78.56). Clinical disease staging in our series was as follows: IA (n=2), IB (n=1), IIA (n=1), IIIA (n=2), IIIB (n=5), stage IV (n=1), and 1 patient refused complete tumor staging. These findings diverge from the high incidence of early stage lung cancer described in other series.4,8

All patients were evaluated by the thoracic tumors committee of our hospital. Their final decision was surgical treatment in 3 cases, oncological treatment in 5 (4 chemotherapy and 1 chemotherapy and radiation therapy), and symptomatic treatment in 5 patients, in view of their functional status. At a second evaluation, patients undergoing surgical treatment (after a minimum disease-free period of 6 months) were assessed by the interstitial diseases committee, and treatment with antifibrotic drugs started in 66 % (pirfenidone in all cases). The other patients continued close clinical and functional monitoring, given their absence of symptoms. None of the patients who underwent surgical treatment presented IPF exacerbations and/or postoperative complications, despite thoracic surgery being one of the possible etiologies of acute exacerbation.11 No statistically significant differences were found in the histological LC type or in the stage at diagnosis in the subgroup of CPFE patients.

Taking into account the limitations of the study, such as the differing follow-up times due to the low incidence of cases, 54 % of patients in the series have now died (n=7). In the group of patients who died, the average survival from diagnosis of IPF was 9 months (SD: 80.54). This figure was higher in patients who received antifibrotics (mean survival 22 months). Mean survival from diagnosis of LC was 10.5 months (SD: 11.39), but 66 % (n=2) of the subgroup of patients who underwent surgical treatment are still alive; the only patient from this group who died had a survival of 39 months. The subanalysis of the CPFE group revealed a similar overall mortality (60 %) with an average survival after LC diagnosis of 5.3 months (SD: 3.68).

In our series, as in other previously described cohorts, IPF appears to be the determining factor in life expectancy,8,12 and the option of surgery must be considered in selected cases. An appropriate, detailed functional assessment of the patient is essential to optimize treatment on an individual basis. We firmly believe in the need for thoracic tumor and interstitial pathology committees to work together to design a joint approach.

Although these results must be interpreted with caution, they suggest that radiological monitoring required for diagnosing IPF could include the early detection of LC, and perhaps this previously anecdotal association will become an increasingly common finding in clinical practice. The need for specific personalized radiological monitoring by tomography aimed at detecting early stage LC in this selected population must be evaluated.

As it is impossible to grant authorship to everyone, we would like to express in writing in this publication our appreciation of all the members of the Thoracic Oncology Committee of the Hospital Clínico de Valladolid and the Interstitial Diseases Committee of the Hospital Clínico de Valladolid.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez BdV, Vicente CD, Figueroa VR, Castro RL, Matilla JM, Pedreira MRL, et al. Asociación entre fibrosis pulmonar idiopática y neoplasia pulmonar. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:47–49.