Penicilliosis is an opportunistic infection in HIV-infected and other immunocompromised patients mostly in Southeast Asia, Southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, with respiratory manifestations in about one-third of patients. We report the case of a 26-year-old non-HIV immunocompromised patient presenting with an airway obstruction caused by penicilliosis, together with a review of the literature of this rare condition.

La peniciliosis es una infección oportunista que se da en pacientes con infección por el VIH y otros pacientes inmunodeprimidos, sobre todo en el Sudeste Asiático, el sur de China, Hong Kong y Taiwán. Se producen manifestaciones respiratorias en alrededor de una tercera parte de los pacientes. Presentamos aquí el caso de un paciente de 26años de edad inmunodeprimido, sin VIH, que comenzó con una peniciliosis endobronquial que obstruía las vías aéreas, junto con una revisión de la literatura de este trastorno muy poco frecuente.

Penicilliosis is an infection caused by Penicillium marneffei, a thermally dimorphic fungus. At room temperature (25°C), it exhibits morphology characteristic of a mold, but grows in yeast-form when found in host tissues or in culture at 37°C. P. marneffei is limited geographically to Southeast Asia, Southern China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Although it has been suggested that bamboo rats are a reservoir for this fungus, the specific reservoir for transmission to humans remains unclear.

In man, P. marneffei is an opportunistic fungus that affects HIV-positive and other immunocompromised patients. Ingestion or inhalation of fungus conidia could be the mode of transmission. Although the most common forms of presentation are non-specific and consist of low-grade fever, weight loss and anemia, the characteristic skin lesion is a central umbilicated papule. Since it is usually present, it is an important key to diagnosis.1 Respiratory symptoms occur in around one third of patients, and diffuse reticulonodular, diffuse reticular, localized alveolar or localized reticular infiltrates, as well as cavitated lesions, can be identified on chest radiographs.2 We describe the case of an immunocompromised patient who presented with obstruction of the right lower lobe bronchi caused by penicilliosis. We also present a literature review of this very rare condition.

Case ReportIn April 2013, a 26-year-old man came in with fever and productive cough. He had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) in 2002 on the basis of a malar rash, positive anti-nuclear antibody and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody tests, and class IV lupic nephritis with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. His symptoms improved following corticosteroid and azathioprine treatment, which was gradually tapered off until it was discontinued in 2010. Two years later, the patient presented cervical lymphadenopathies. Mycobacterium abscessus was identified in lymph node and blood cultures. Treatment was established with clarithromycin, doxycycline and levofloxacin. Six months later, the blood cultures were negative for Mycobacterium, and the lymphadenopathies had regressed.

When the patient first came to the clinic, he had fever, with a body temperature of 38.2°C and normal oxygen saturation (SpO2 99%). Physical examination revealed fine crackles in the right lower lobe, but was otherwise unremarkable. There were no signs of skin lesions, lymphadenopathies or hepatomegaly.

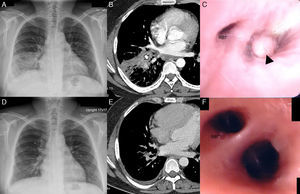

Laboratory test results showed mild leukocytosis, normal routine serum biochemistry and negative HIV serology. Chest radiograph revealed a mottled ground glass opacity and consolidation at the level of the right lower lobe (Fig. 1A). Sputum Gram-staining and acid-fast bacilli testing were negative. Empirical treatment for bacterial pneumonia with imipenem–cilastatin was started, but the patient's clinical condition and chest radiograph did not improve. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a consolidation in the right lower lobe and luminal stenosis of the basal segmented bronchi (Fig. 1B). There were also multiple small mediastinal lymph nodes.

(A) Chest X-ray on initial presentation, in which a mottled ground glass opacity and consolidation at the level of the right lower lobe can be seen. (B) Chest computed axial tomography (CT) image in a mediastinal window setting, showing an area of consolidation at the level of the right lower lobe, with an endobronchial lesion obstructing the basal segmented bronchi (arrow). (C) Bronchoscopy revealed a whitish endobronchial mass (arrow) at the opening of the basal anterior, lateral and posterior segmented bronchi of the right lower lobe. The follow-up chest X-ray (D) and chest CT (E) showed improvement of this lesion. The basal segmented bronchi in the right lower lobe were restored and identified on the chest CT (E) and in the bronchoscopy image (F). RB7: medial basal segmented bronchus of the right lower lobe.

Bronchoscopy performed one day later showed a whitish endobronchial mass at the opening of the basal anterior, lateral and posterior segmented bronchi of the right lower lobe (Fig. 1C). Histopathological examination of the endobronchial biopsy revealed acute and chronic inflammation with no granuloma formation. However, Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) staining showed a sausage-shaped yeast-type organism, long and oval with clear central septa. Tissue and bronchial lavage cultures were positive for P. marneffei.

The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin B (1mg/kg/day). The fever subsided after 5 days, and after 2 weeks treatment was switched from intravenous amphotericin B to oral itraconazole (400mg/day). Two months later, the follow-up chest radiograph showed notable improvement in the lesions in the right lower lobe (Fig. 1D). The follow-up CT scan revealed only minimal residual ground glass opacity, interstitial thickening and slight peribronchial thickening in the previously affected areas (Fig. 1E). Repeat bronchoscopy showed complete resolution of the endobronchial lesion (Fig. 1F). After 6 months, oral itraconazole treatment was reduced to 200mg/day for prophylaxis.

Given the patient's history of 2 opportunistic infections (M. abscessus and P. marneffei) despite all immunosuppressant drugs having been discontinued for 2 years, underlying immunodeficiency was suspected. Anti-interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) antibodies were analyzed, confirming the diagnosis of adult-onset immune deficiency.3

DiscussionEndobronchial fungal infection is a very rare manifestation compared to other forms of presentation of fungal lung infections. The most common fungi causing endobronchial infection are Aspergillus spp., Coccidioides immitis, zygomycetes, Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans and Histoplasma capsulatum.4 Endoscopic findings differ in the various fungi, but definitive diagnosis requires microbiological identification (smears, culture or histopathology sections).

Pulmonary penicilliosis usually manifests as parenchymal or interstitial lesions. Endobronchial penicilliosis is much rarer. It can occur in immunocompromised hosts with or without HIV, and even in immunocompetent hosts.5 As far as we know, there have only been 4 cases in HIV patients,6–9 one case in an HIV-negative immunocompromised patient,10 and one case in an immunocompetent patient reported in English language publications (Table 1).

Summary of Endobronchial Penicilliosis Patient Characteristics.

| Case | First author | Sex, age (years) | Immune status | Time since disease onset | Respiratory symptoms | Characteristics of the endobronchial lesion | Location | Associated symptoms | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhiyong6 | M, 26 | AIDS, CD4 8/μl | 2 months | Cough | Nodule | Opening of LB 10 | Fever, weight loss | Amp B+Itra 2 weeks followed by Itra | Improvement |

| 2 | McShane7 | M, 35 | AIDS, CD4 20/μl | 3 months | Cough, difficulty breathing | Tumor-type | Posterior tracheal wall | Fever, skin lesions, lymphadenopathies | Amp B 2 days followed by Itra | Improvement |

| 3 | Chau8 | M, 22 | AIDS, CD4 10/μl | 2 weeks | N/A | 2–3mm papules | N/A | Fever, weight loss, skin lesions, lymphadenopathy | Itra | Improvement |

| 4 | Huang9 | M, 46 | AIDS, CD4 N/A | 10 days | Cough, dyspnea | Multiple whitish spots | Opening of the upper part of the LUL bronchus | Fever, weight loss | Intravenous Fluc. 2 weeks followed by Itra. | Improvement |

| 5 | Hsu10 | M, 14 | ALL | N/A | Cough, dyspnea | 5cm digitiform mass | RLL bronchus | Fever | Expectoration, Itra | Improvement |

| 6 | This case | M, 26 | Adult-onset immunodeficiency | 5 days | Cough | Whitish mass | Opening of RB 8,9,10 | Fever | Amp B 2 weeks followed by Itra. | Improvement |

| 7 | Joosten5 | M, 45 | Immunocompetent | 4 months | Cough, pleuritic pain | Polypoidal mass | Opening of the lingular bronchus | Fever, lymphadenopathy | APC, Amp B duration N/A followed by Itra | Improvement |

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; Amp B: amphotericin B; APC: argon plasma coagulation; Fluc: fluconazole; Itra: itraconazole; LB 10: bronchus of the posterior lobe of the left lower lobe; LUL: left upper lobe; M: male; N/A: not available; RB 8,9,10: bronchi of the anterior, lateral and posterior segments of the right lower lobe; RLL: right lower lobe.

The characteristics of patients with endobronchial penicilliosis described in case reports essentially did not differ in terms of their underlying immune conditions. The duration of symptoms varied from days to months. All cases involved fever and cough. Extrapulmonary involvement was also identified. The locations of the endobronchial lesions were quite non-specific, ranging in size and characteristics from a small papule, nodule or spot to a mass obstructing the airways.

All patients responded well to anti-fungal medication, and fever generally subsided within 1 week with treatment. The chest radiographs gradually improved over a period of months, leaving some residual infiltrates.

Adult-onset immunodeficiency should be suspected in HIV-negative patients who present repeated episodes of infections caused by rare intracellular pathogens, namely, nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), fungal infections (e.g. cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, penicilliosis), disseminated herpes zoster infection and non-typhoid Salmonella bacteremia that cannot be explained by any underlying acquired immunodeficiency, and who are not taking immunosuppressive drugs. Lastly, positive IFN-γ autoantibodies are the hallmark for diagnosis.3 IFN-γ plays an important role in the cellular immune response by activating macrophages to phagocytoses and destroy intracellular pathogens. An IFN-γ deficiency, therefore, would impair the ability of the macrophages to destroy the intracellular microorganism. Our patient was diagnosed with SLE, which is also an autoimmune disease. Although autoantibodies play an important role in both SLE and adult-onset immunodeficiency, they target different cells. As far as we are aware, there have been no published cases in which a correlation between these 2 diseases is mentioned. Consequently, the coexistence of SLE and adult-onset immunodeficiency in our patient could be a coincidence.

In conclusion, we present a case of endobronchial penicilliosis in a patient with adult-onset immunodeficiency. As this is a very rare respiratory manifestation, extensive medical knowledge is needed for the physician to bear in mind this particular infection, and to request the best examination (bronchoscopy) to reach a definitive diagnosis.

FundingNone.

Authors’ ContributionViboon Boonsarngsuk and Dararat Eksombatchai are involved in patient care, review and drafting of the manuscript. Wasana Kanoksil is involved in histopathology interpretation. Visasiri Tantrakul is involved only the patient care.

Conflict of InterestWe declare that we have no conflict of interests and that we have no financial relationship with any commercial entity that may have interests in the topic discussed in this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Boonsarngsuk V, Eksombatchai D, Kanoksil W, Tantrakul V. Peniciliosis endobronquial: presentación de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:e25–e28.