Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disease caused by an alteration in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene.1 This alteration determines abnormal ion transport, primarily in the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system.2 Early neonatal screening detection using immunoreactive trypsin testing has shown benefits in the long term, and for this reason, the disease is usually diagnosed in children. However, recent studies indicate a prevalence of CF diagnosis in adults of up to 10%.3,4 The diagnosis is established in the presence of clinical criteria or a family history of CF and the demonstration of abnormal CFTR function from the result of a sweat test or the presence of 2 mutations causing the disease.4

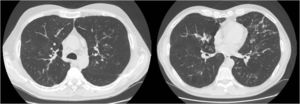

We report the case of a 52-year-old man, former smoker of 35 pack-years, with a family history of respiratory disease, mother with asthma, and father with pulmonary emphysema, and no other significant history. He was admitted to the intensive care unit with hypercapnic encephalopathy with no clear triggering factor, and required intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation. He had a history prior to admission of several years of habitual cough and expectoration, and Medical Research Council (MRC) grade 1–2 dyspnea that had worsened in recent months. On discharge he was referred to the respiratory medicine department for an extended study, which found MRC grade 2 dyspnea with no other relevant findings. Lung function tests were requested, according to the 2002 SEPAR guidelines, which revealed a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 2150cc (51.7%), a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 650cc (19.4%), FEV1/FVC ratio of 30.5%, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide corrected by the alveolar volume (KCO) of 56%, and 6-minute walking test distance of 576m (98.5% predicted) but with desaturation of 76%. Arterial blood gas showed chronic global respiratory failure, as follows: pH 7.41, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) 52mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) 52mmHg, and oxygen saturation (SaO2) 86%, so home non-invasive mechanical ventilation continued. A chest computed tomography (CT) was also requested, and showed centrilobular emphysematous involvement of the pulmonary parenchyma, areas of bronchiectasis mainly in the upper fields and the perihilar and basal regions, with cystic formations (cystic bronchiectasis) and pseudonodular areas in the lingula and lower lobes associated with mucoid impaction (Fig. 1). Given these findings, the patient was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic respiratory failure, and bronchiectasis pending classification. Several additional tests were requested to determine the etiology of the bronchiectasis (immunodeficiencies, alpha-1 antitrypsin, Mantoux, etc.).5 Of interest was a positive sweat test of 84 mEq chloride per liter, which was followed up with a genetic study. The patient was not a carrier of any of the 52 mutations that were studied, although complete sequencing of the gene was not performed. Accordingly, we diagnosed our patient with adult CF.

Bronchiectasis is the third leading cause of chronic obstructive respiratory disease in adult patients. As it is not a disease in itself but rather the consequence of other processes, it is of great importance to establish its etiology in order to choose the most appropriate treatment.5 Despite the fact that the prevalence of bronchiectasis is approximately 50% in moderate-severe COPD,6 it should not be assumed to be a direct result of COPD, and a differential diagnosis with other associated disorders should be performed.

There are approximately 70000 individuals with CF worldwide.7 In recent decades, notable improvements in medical management, particularly with regard to pulmonary involvement, have led to an increase in life expectancy in these patients,8–10 and now 40%–50% of CF patients are adults.3

Most patients present the classic CF symptoms in childhood, and diagnosis is made in the first year of life.11 Patients who are diagnosed in adulthood often have one of the so-called “mild” mutations and have retained some chloride channel activity.1 These patients have what is known as non-classic CF, and often present fewer symptoms with the involvement of fewer organs or systems.

In spite of advances in the treatment of CF, respiratory manifestations continue to dominate the characteristic symptoms of CF patients, as was the case with our patient, and respiratory problems account for 95% of the morbidity and mortality of this disease.12,13 Pulmonary involvement in patients with classic CF includes bronchiectasis mainly in the upper lobes, recurrent lung infections, mucoid impaction that may be associated with chronic bacterial infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, pneumothorax, atelectasis, and even pulmonary hypertension (PHT) and cor pulmonale.14 Adult CF presents as non-classic CF and the pulmonary manifestations may be absent or milder than in the typical manifestation of the disease.

The adult patient should receive comprehensive and personalized care in experienced, multidisciplinary CF units. The main objective of symptomatic treatment is to delay disease progression. Moreover, a genetic study can guide the prescription of treatments targeting specific mutations, such as ivacaftor, which modulate the CFTR protein defect in 9 of the known CF mutations, and have opened the way for the development of other disease-modifying drugs.15

This case demonstrates how a patient with emphysema and severe airflow obstruction, who in principle raised no diagnostic suspicions, could surprise us with a diagnosis that, although rare, radically modifies management and prognosis, thus highlighting the importance of the complete study of all patients with bronchiectasis.

Please cite this article as: Benito Bernáldez C, Almadana Pacheco V, Valido Morales AS, Rodríguez Martín PJ. Fibrosis quística del adulto, una causa de bronquiectasias a considerar en el paciente con EPOC. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:163–164.