Identification of molecular targets in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents a major paradigm shift. Detection of EGFR mutations, present in 10–20%1 of European NSCLC patients, predicts response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib or osimertinib. Although these drugs are highly effective in this selected population primary resistance can be observed in 30% of patients.2 Molecular mechanisms implicated in primary resistance are currently being explored.3 Additionally, resistance to these agents invariably develops after a median of 9.2–14.7 months,4 process known as acquired resistance.

Here we describe the case of an 85-year-old male patient with an EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma who probably did not receive the best therapeutic approach. The patient was a never smoker. He had a history of hypertension, vitamin B12 deficiency associated anemia and osteoarthritis.

He presented in the emergency department with a 15-day history of dyspnea. On physical examination, he presented tachypnea and, on auscultation lung sounds were normal. Blood test showed no signs of infection. The computed tomography of the chest revealed a bilateral pulmonary embolism, as well as a solid mass measuring more than 7cm in the right upper lobe, with enlarged lymph nodes at both mediastinal and ipsilateral hilar regions. Imaging also showed pleural effusion and bone, adrenal and liver lesions consistent with metastases. A liver biopsy was performed for diagnostic purposes.

While waiting for pathologic and molecular diagnosis the patient had progressive dyspnea and worsened hypoxemia, with a decline in the oxygen saturation. Non-invasive ventilation was initiated. As the patient was a non-smoker, a liquid biopsy was obtained for EGFR testing. Real-time PCR (Therascreen) results in 24h detected an EGFR L858R mutation on exon 21. Treatment with gefitinib at 250mg daily was initiated. Unfortunately, the patient failed to respond, and died after 7 days on treatment.

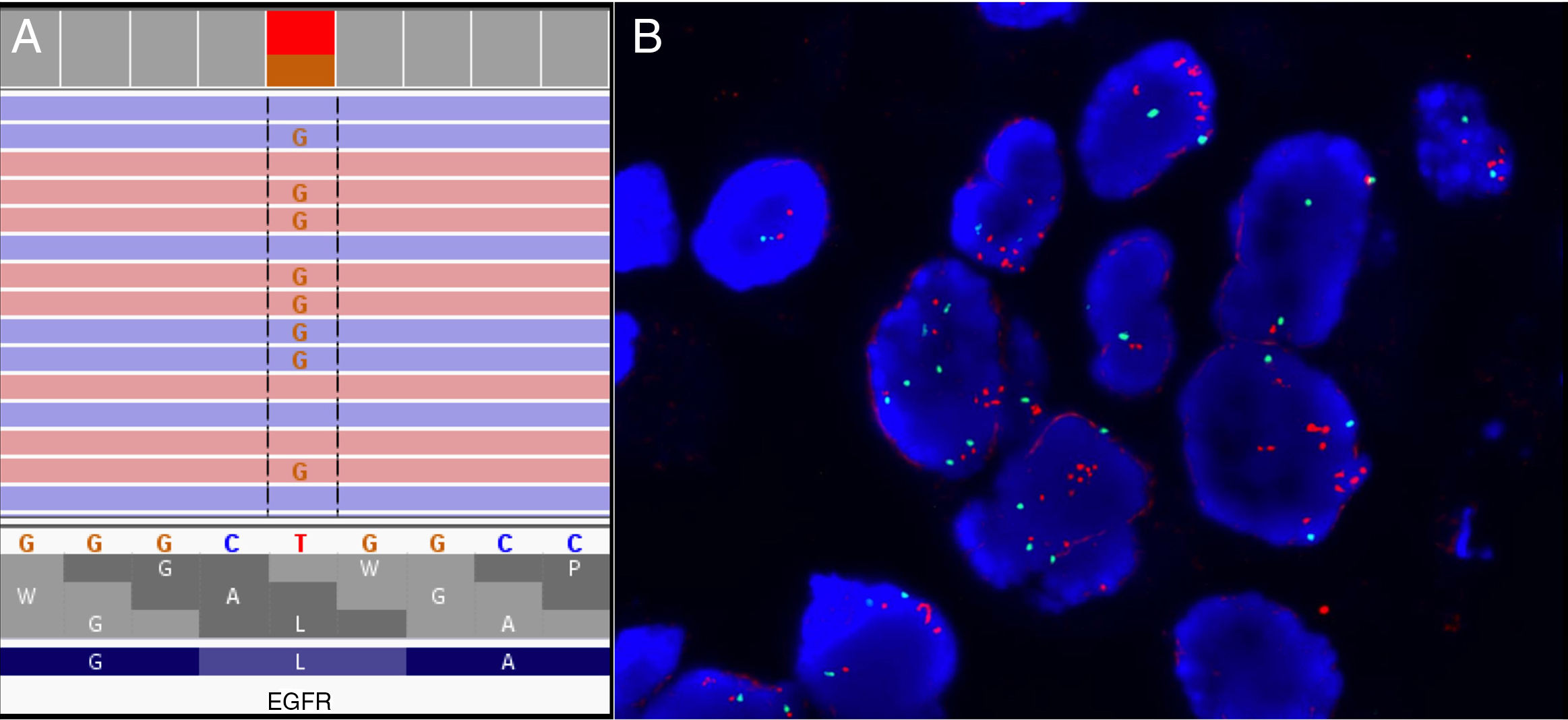

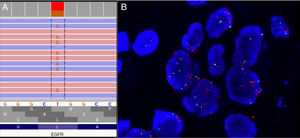

The pathological evaluation of the liver biopsy was consistent with a metastasis from a lung adenocarcinoma with PDL1 (28.8) positivity in 40% of cancer cells. The next generation sequencing (NGS) targeted panel Oncomine Focus Assay DNA and RNA showed the EGFR mutation on exon 21 (Fig. 1A) as well as a MET amplification with a MET copy number of 5.67 and a TP53 mutation. This MET amplification was subsequently confirmed by FISH (Fig. 1B).

Primary resistance to EGFR TKIs is defined as disease progression during the first 3 months of treatment without any evidence of objective response. Mechanisms involved in acquired resistance, such as T790M, MET amplification, PTEN loss and ERBB2 amplification can contribute to primary resistance.3 A recent analysis by NGS of a small series of patients with EGFR mutations by Zhong et al.3 identified novel potential primary resistance mechanisms such as mutation of TGFR1 or single-mutation patterns (cytosine spontaneous deamination). In this work, MET amplification was identified as one of the most frequent mechanism of primary resistance.

Our patient showed a high level MET amplification with a ratio >5 that probably would have contributed to a lack of response to EGFR targeted therapy. Sequential gene testing has been until recently the most common way of molecular diagnosis in patients with advanced NSCLC. This is currently being substituted by multiplex testing by NGS techniques that allows for testing of multiple genomic alterations relevant to the patient care. Our case represents one of the situations were upfront multiplex testing would have allowed a more informed decision on patient care with a more appropriate selection for the therapeutic approach.

Comprehensive genomic analysis by NGS has brought a new scenario to the lung cancer diagnostic field and will probably impact positively in the outcome of patients.