One of the few positive features of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been the significant reduction in paediatric hospital admissions and attendances to urgent care settings.1 Early evidence from China and Italy indicated that children fared better than adults with lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, a lower incidence of severe disease and minimal mortality.2–4 The reduction in attendances however includes other anticipated illnesses which would not have been predicted. In our hospital we have noted a marked reduction in children and young people presenting with acute asthma/wheeze.

We reviewed the numbers of acute hospital presentations with wheeze/asthma in children aged 1–17 years of age over the four weeks prior to the UK national lockdown on March 23rd 2020 and the 8 weeks afterwards. For comparison, we reviewed presentations in the same calendar weeks in 2017–2019. Our paediatric asthma nurses record every acute wheeze/asthma attendance at St George's Hospital in South West London on a daily basis allowing direct comparison.

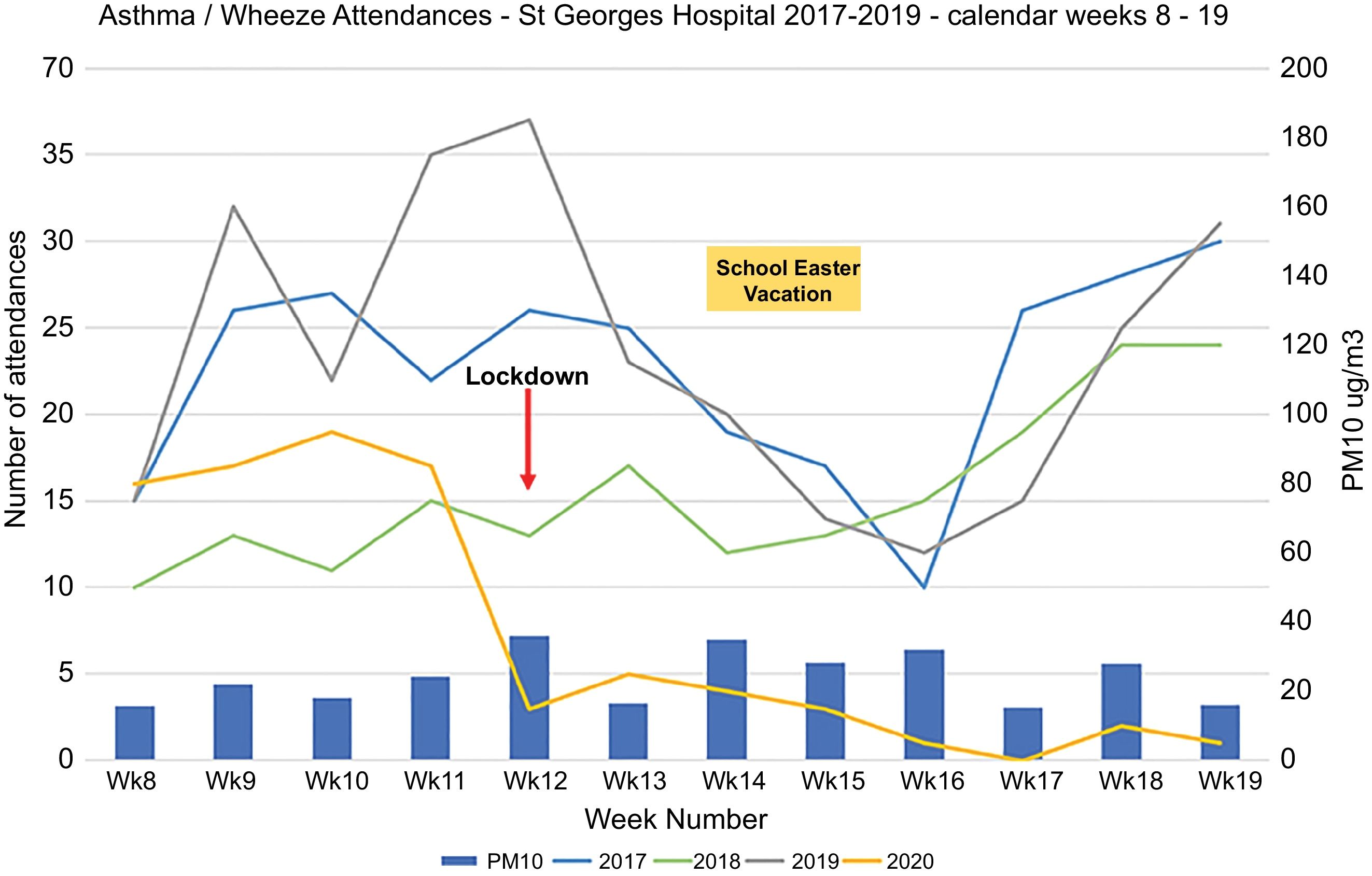

The figure shows the total number of emergency attendances for each week during the 12-week period for each year (Fig. 1). In 2020, prior to the lockdown, an average of 17 children (range 16–19) presented each week and was comparable to attendance rates in 2017–2019. This fell to 2 acute presentations per week (range 0–5) in the eight weeks after the national lockdown. In previous years, although there were trends to lower admissions corresponding to the school spring vacation (weeks 14–16), the comparative numbers of attendances remained consistently higher. Even though some families may have taken pre-emptive action prior to the government announcement, the significant fall in attendances coincided at the point of the Government announcement. Overall there has been a 90% reduction in attendances over the 8 week lockdown period compared to 2017–2019.

There are a number of potential factors which may have impacted on this observation. Our initial concern was that patients/parents were avoiding presentation to hospital due to concerns about the risk of exposure to COVID-19 in hospital and in response to the government instructions to ‘stay home’. Against this, our asthma nurses have not dealt with increased numbers of parents phoning for advice about acute management. Furthermore, those families contacted for routine asthma reviews report good health. The numbers have also continued to fall through the lockdown and we haven’t seen children with more severe symptoms associated with delayed presentation. Despite early concerns in the safety of using inhaled corticosteroids with SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are anecdotal reports of improved adherence to controller medications.

A second positive benefit from the lockdown has been the potential improvement in air quality due to the enforced reduction in road and air travel. Data from the European Environment Agency indicate generally lower NO2 and PM10 levels this year compared to the same time period in 2019.5 However average daily levels of PM10 (shown in figure) and NO2 from monitors in our locality do not indicate a change in these pollutants in SW London potentially affected by other atypical atmospheric conditions.

The abrupt fall in attendances coincided with the wide scale closure in schools along with the implementation of social distancing. In closing schools, children may also have reduced exposure to pollution on the school run and have undertaken less formal exercise. We propose the most likely impact is in the reduction of spread of other typical respiratory viruses. A similar, partial effect may be seen during school vacations but is amplified at present by the more pronounced isolation and hygiene messages associated with the pandemic. Whilst this data does not show causation, and recognising the effects are probably multifactorial, it is important to reflect on the information gained during this unique time. In the UK, asthma/wheeze remains one of the highest causes for school absence and hospital admissions with wider ramifications on society. We should question what inadvertent harms are potentially caused by our systems. Class sizes of 30 children or more in small, overcrowded classrooms, narrow corridors, and lax personal hygiene practices may all likely contribute to high levels of viral spread within the school institution environment. As the lockdown relaxes and schools restart, it will be important to monitor how quickly acute asthma presentations increase. With this information it may be prudent for government to review education strategies to improve the learning environment and reduce the risks of inadvertent harm. Whilst children have been relatively spared the physical ravages of SARS-Cov-2 infection, their lives will have been affected educationally, emotionally and longer term financially by the pandemic. It is important that we learn what lessons we can for their benefit and their future.