Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is a frequently occurring disease which has increased in incidence over the last years and is associated with considerable mortality.1 PE survivors are at risk for recurrent PE, anticoagulation-associated bleeding and cardiovascular events, but also face the possibility of developing persistent, sometimes disabling symptoms.2,3 Up to half of the PE patients report persistent dyspnea and/or functional limitations despite adequate anticoagulant treatment, qualifying for the post-PE syndrome (PPES).3–6 PPES is defined as the presence of any of the following, despite adequate anticoagulant treatment for ≥3 months: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease (CTEPD), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), post-PE cardiac dysfunction (characterized as persistent right ventricle impairment after an acute PE) or post-PE functional impairment.7 Post-PE functional impairment is the most frequent cause of PPES. The hypothesis of the pathophysiology of post-PE functional impairment is that less physical activity due to dyspnea after an acute PE results in deconditioning, leading to exercise limitation and further deconditioning.3–6,8,9 In addition, depressive disorders, fear for complications or recurrences and post-thrombotic panic syndrome further contribute to physical inactivity and impairment in both professional and social activities.10–12 Post-PE functional impairment has been shown to lower quality of life (QoL) and increase the risk of depression and subsequent permanent work-related disability.9,13–15 To improve the overall health outcomes of patients with acute PE, adequate measures to diagnose PPES and strategies to prevent and treat PPES are of the essence.

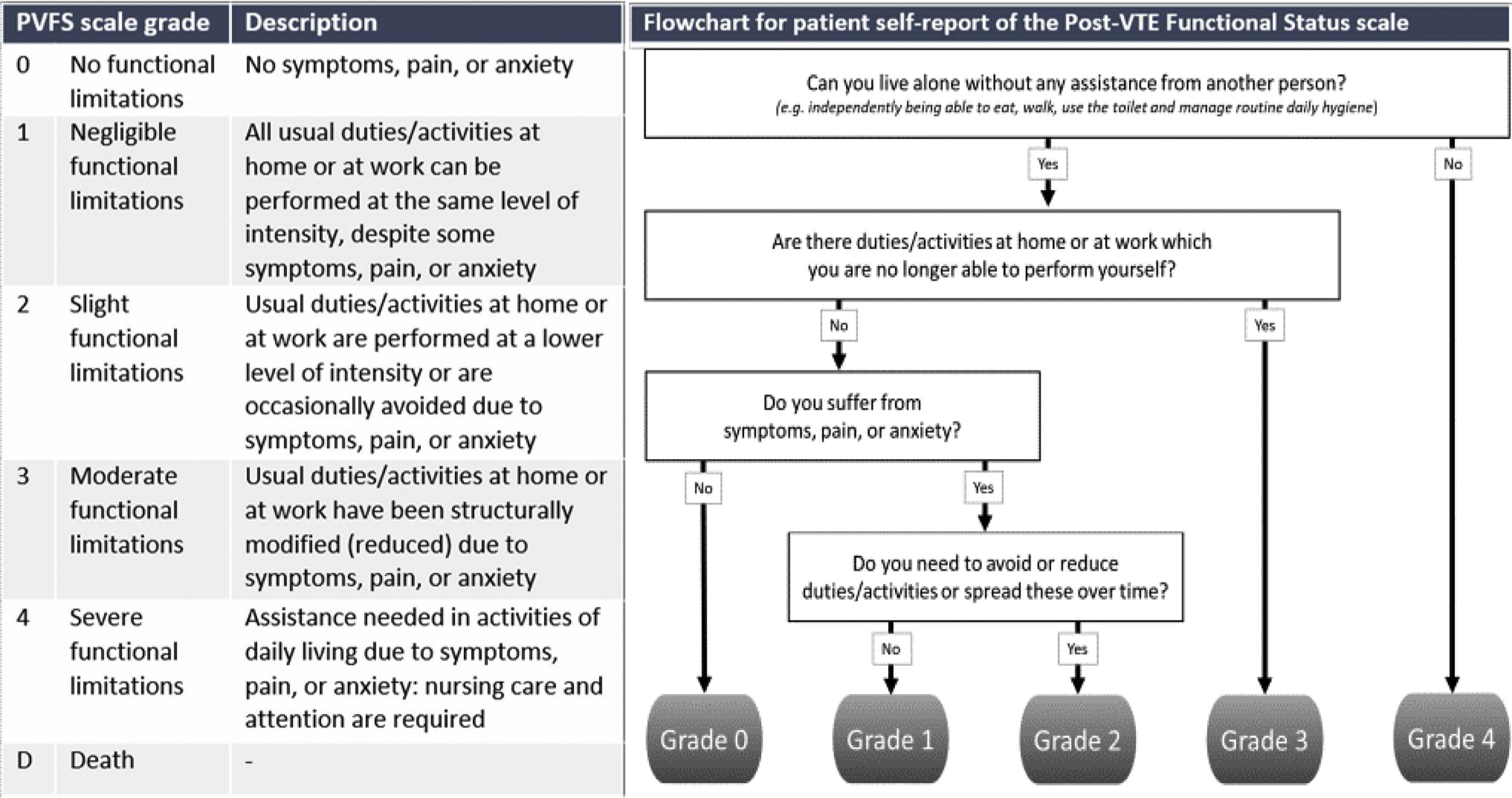

How to diagnose post-PE syndromeThe first priority in the management of patients with PPES is to diagnose CTEPH early, which will lead to improved survival and better quality of life by itself.16–18 Patient reported outcome measures (PROMS) are great tools to reproducibly evaluate the presence of persistent symptoms. This can be done by utilizing PROMS for specific symptoms such as dyspnea, but also by using the Post-VTE Functional Status (PVFS) scale, which measures persistent limitations in daily life following PE providing a holistic view on the patients’ recovery (Fig. 1).19,20 The PVFS scale captures the entire spectrum of functional outcomes in six scale grades, covering both limitations in usual activities or duties as well as changes in lifestyle.19,20

Flowchart for patient self-report of the Post-VTE Functional Status Scale.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on PE recommend echocardiography as a first step in patients with persisting dyspnea, functional limitations or risk factors for CTEPH. A low probability of pulmonary hypertension on echocardiography reasonably rules out CTEPH.21 Another strategy for ruling out CTEPH is the use of a CTEPH prediction score and the CTEPH rule-out criteria to select patients in whom echocardiography is indicated.22–24 Assessing the index computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for signs of CTEPH or chronic PE also contributes to the optimal selection of patients benefitting from early follow-up with echocardiography.25,26 A CTEPH diagnosis should always be confirmed by right heart catheterization.16 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and spirometry can be used to identify an alternative explanation for persisting symptoms after an acute PE if CTEPH is ruled out.16

How to treat post-PE syndromeExercise training is suggested to be the ultimate treatment of PPES without CTEPH, CTEPD or other cardiopulmonary comorbidities. Indeed, several studies have shown that exercise therapy is safe and effective in PE patients.27–32 An Austrian study showed that patients who received a 6-week pulmonary exercise training (median time between PE event and start of rehabilitation of 19 weeks) had a significant improvement in 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT; mean difference 49.4meters) and self-reported symptom severity.29 A Dutch study showed that cardiopulmonary rehabilitation resulted in improved training intensity, PE-specific QoL, fatigue and PVFS scale grade.33

It has been suggested that in order to prevent deconditioning and consequently PPES, exercise training should be performed early after the PE diagnosis.

A Danish study compared an 8-week home-based exercise program 2–3 weeks after PE diagnosis with a control group. Results showed an improvement on Shuttle Walk test (SWT; mean difference 25 meters) and PE-specific QoL scores (mean difference 3.0 points) for the intervention group compared to the control group, but the primary hypothesis was rejected as group differences were nonsignificant.28 An Iranian randomized controlled trial (RCT) included 24 patients with intermediate-high risk acute PE: patients who received an 8-week high-intensity interval training showed a significant improvement of VO2max, right/left ventricle ratio diameter and health-related QoL compared to the control group.34 Notably, in these 2 studies, patients were not selected to participate based on presence and severity of symptoms, and patients with little or no remaining symptoms may have been included. Hence, it is likely that the benefit of an early exercise intervention will be more pronounced in patients who do not report to be largely recovered 2-4 weeks after the PE diagnosis.

Long COVIDSimilar to PPES, a large number of 22-96% of patients with COVID-19 suffer from persistent symptoms after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, qualifying for ‘long Corona Virus Infection Disease-19’ or ‘long COVID’.35–42 The pathophysiology of long COVID is unknown, but is likely multifactorial. Since the incidence of thromboembolic events in COVID-19 is high43–45, PPES may be a relevant determinant of long COVID.42 As with post-PE functional impairment, reduced exercise capacity associated with deconditioning likely also plays an important role.46,47 To identify patients with functional impairment, the Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale can be used.48 The PCFS scale, based on the PVFS scale, has been applied in several studies investigating functioning after COVID-1949–52 and its good reliability and construct validity have been demonstrated.53–56 In line with PPES, after CTEPH and CTEPD have been ruled out, rehabilitation programs may contribute to a reduction of symptoms of long COVID.57–60 For instance, one RCT has demonstrated improvement in respiratory function, QoL, and anxiety after a 6-week respiratory rehabilitation program after hospital discharge in elderly post-COVID-19 patients (aged ≥65 years).61

ConclusionPPES includes a broad spectrum of clinical presentations, of which CTEPH is the most rare but also most relevant with regard to survival. Applying PROMS is very helpful for standardizing follow-up, for instance using the PVFS scale. In PPES patients, without CTEPH and CTEPD, cardiopulmonary rehabilitation provides a good treatment option. Further studies are required to increase our understanding of optimally selecting patients for and optimal timing of exercise interventions.