Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a heterogeneous group of lung disorders characterized by inflammation and scarring of the lung tissue.1,2 A total of 13–40% of patients with ILDs1 develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), similar to that observed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). PPF is associated with worsening respiratory symptoms, a decline in lung function and early mortality.3,4

Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that reduce the progression of lung fibrosis.5 Recent international guidelines recommended nintedanib as a treatment for IPF and PPF. Unfortunately, nintedanib is not exempt from side effects.6 Diarrhoea is the most frequent adverse event associated with nintedanib treatment (up to 70%).7 Diarrhoea causes loss of appetite due to gastrointestinal discomfort, dehydration, and weight loss.8 In addition, it makes it difficult to adhere to treatment and increases the number of consultations with health professionals of different categories and specialties.8 This situation could lead to reducing the recommended dose and even suspending treatment.6

Recently, the efficacy of ramosetron, a serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) type 3 (5-HT3) receptor inhibitor, was reported in 2 patients with diarrhoea due to nintedanib,9 after 3 days of treatment; however, the response rate was 35% when administered for 1 month in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.10 In the case of loperamide, their administration has been described in previous studies of the use of nintedanib in patients with IPF, but their efficacy has not been reported.11

The carob tree is a plant used in traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders since it has anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antidiarrhoeal, antioxidant, antiulcer, anticonstipation and anti-absorption effects on glucose in the gastrointestinal tract.12 In our ILD unit, we have been using carob flour to treat diarrhoea in patients on nintedanib therapy. Here, we report our experience with the use of carob flour in the management of diarrhoea in patients treated with nintedanib.

In this observational retrospective analysis from our ILD unit, we included patients treated with nintedanib, between October 2021 and May 2022, who presented with diarrhoea during the treatment and received carob flour to manage it. We excluded patients who presented with diarrhoea secondary to other gastrointestinal disorders or those who for medical reasons had to reduce or suspend their treatment. Ethics committee approval was obtained (HCB 2022/0536 Registry).

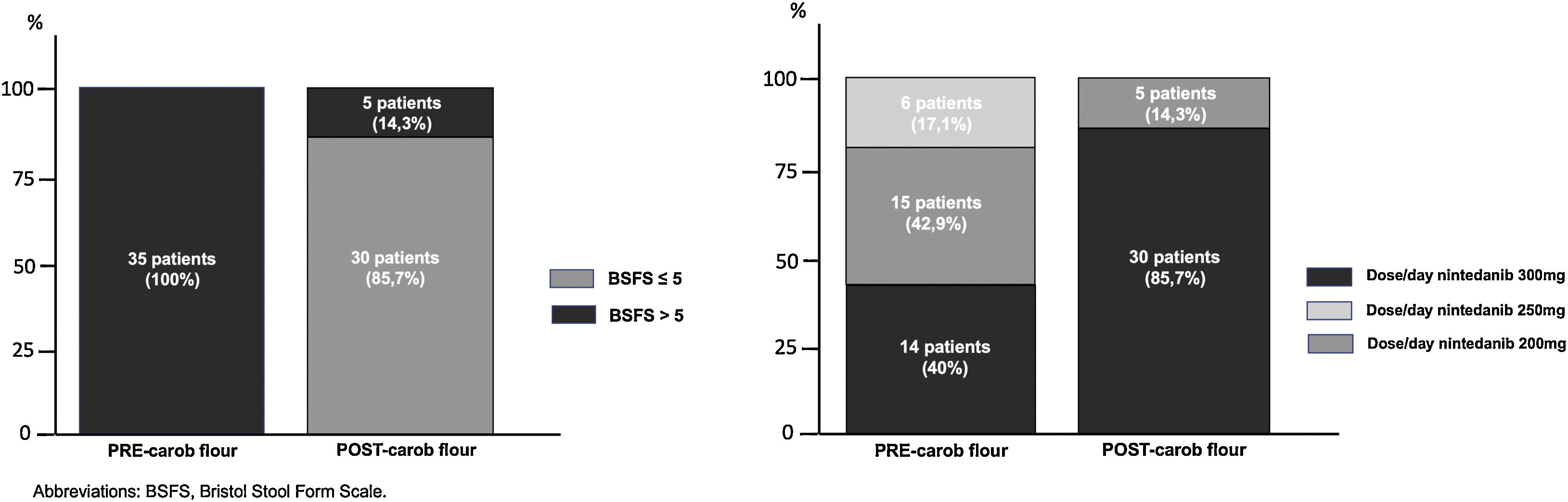

The Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) was applied before and after the initiation of carob flour. The BSFS categorizes stools into one of seven stool types ranging from type 1 (hard lumps) to type 7 (watery diarrhoea).13 During the follow-up, the doses of carob flour and nintedanib were registered. A dose of 7g of carob flour was administered before breakfast (a dessert spoon-sized serving). After 3 days, a follow-up call was made to evaluate the patient's stools according to the BSFS. If the patient continued to have diarrhoea (BSFS higher than 5), we added a 7g dose before dinner. If the diarrhoea persisted, we increased each dose up to 14g (7g twice/day) progressively until stools with a score of 5 or less on the Bristol Scale were achieved. Patients with persistent diarrhoea after consuming the maximum recommended dose of carob flour were considered nonresponders.

All data are expressed as the means, standard deviations (SD) or medians with the 25th and 75th percentiles depending on the distribution. The distribution was analysed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between groups were evaluated using Student's t-test for normally distributed variables or a Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric variables. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS version 25.0 package (SPSS, Chicago, USA).

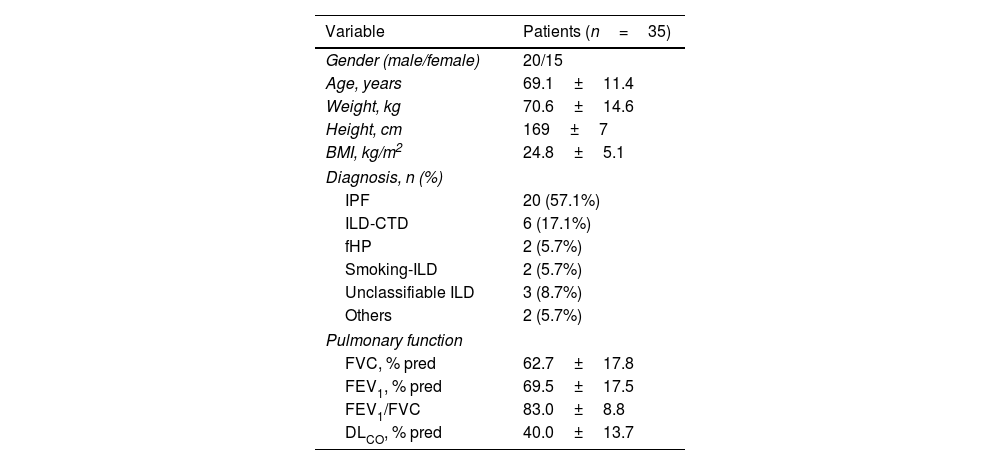

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included patients (n=35). The mean BFSF decreased from 7 (7–7) to 4 (4–5) (p<0.001). The mean number of stools decreased from 4 (3–6) to 1 (1–2) (p<0.001). Thirty patients (85.7%) had a final BFSF of ≤5 (80% of patients with score 3–4). After the intervention, at a minimum of 3 months of follow-up, the number of patients receiving 150mg/12h (the optimal dose of nintedanib)6,7 increased from 40% to 85.7% (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the Included Subjects.

| Variable | Patients (n=35) |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 20/15 |

| Age, years | 69.1±11.4 |

| Weight, kg | 70.6±14.6 |

| Height, cm | 169±7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8±5.1 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| IPF | 20 (57.1%) |

| ILD-CTD | 6 (17.1%) |

| fHP | 2 (5.7%) |

| Smoking-ILD | 2 (5.7%) |

| Unclassifiable ILD | 3 (8.7%) |

| Others | 2 (5.7%) |

| Pulmonary function | |

| FVC, % pred | 62.7±17.8 |

| FEV1, % pred | 69.5±17.5 |

| FEV1/FVC | 83.0±8.8 |

| DLCO, % pred | 40.0±13.7 |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; ILD-CTD: interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue diseases; fHP: fibrosing hypersensitivity pneumonitis; ILD: interstitial lung diseases; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second; DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide.

Three months later, 30 patients (87.7%) remained free of diarrhoea, even those who increased their treatment to full doses of nintedanib (16, 53.3%). Five patients (14.3%) continued to have diarrhoea despite the use of carob flour, and their treatment had to be reduced to subtherapeutic doses. These patients took a mean dose of carob flour of 11.2±3.8g, and no patient presented any episode of allergy or food intolerance. Regarding adverse effects, only 2 patients reported constipation (5.7%).

In our study, we found that carob flour may be helpful in improving diarrhoea associated with nintedanib. In this type of progressive and highly disabling disease, therapeutic adherence must be encouraged for the drug to act optimally. However, adverse reactions such as diarrhoea may lead to discontinuation of treatment. In a recent study, Cottin et al. found that approximately 72% of patients using nintedanib had diarrhoea, leading 48% of patients to lower their dose and 6.2% to completely discontinue the treatment with the consequent risks that this entails.6

Carob flour is an ancient diarrhoeal remedy rich in starch and fibre and it leads to decreased stool output and duration of diarrhoea compared with regular oral rehydration solution since it facilitates water and sodium absorption via the sodium-glucose cotransporter.14 This plant-based food also contains proteins, fats, and minerals that provide more balanced nutrition during diarrhoeal illness.14 The proteins present in carob flour utilize separate glucose–amino acid cotransporters that further promote glucose absorption. By improving stool consistency, these foods can improve nintedanib acceptance, avoiding treatment interruption.14 Other elements, such as the tannins in carob powder, may ameliorate diarrhoea by binding to bile acids and bacterial toxins and inhibiting the growth of bacteria.14

Our study has some limitations. This was a retrospective uncontrolled study carried out in a single centre. Another important limitation was the determination of the ideal dose of carob flour. Additionally, the carob flour is not available in a single-dose format, the amounts self-administered by patients should be not uniform. Future studies should investigate the dose necessary for carob flour to have an optimal effect. Although the protocol of our study establishes the same treatment for all patients, eventually there could be a bias since the patients could have followed different types of diets.

In conclusion, carob flour reduces diarrhoea associated with nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. This pilot report could be the basis for a future controlled multicentre clinical trial.

FundingThis study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project “PI19/01152” and co-funded by the European Union, SEPAR, SOCAP, FUCAP and Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS). Editorial assistance was funded by FUCAP, though an unrestricted grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Spain. Boehringer Ingelheim was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to Boehringer Ingelheim substances, as well as intellectual property considerations.

Conflict of InterestsNancy Perez-Rodas reports support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi, outside the submitted work. Belén Noboa-Sevilla reports support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi, outside the submitted work. Fernanda Hernandez-Gonzalez reports speaker and support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Gebro, outside the submitted work. Jacobo Sellarés reports speaker and consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Gebro, Astra, Chiesi, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare to have no conflict of interest.