Acute bronchiolitis is the most common lower respiratory tract infection in infants under 1 year of age and one of the main causes of hospitalization in childhood.1,2

Some studies show that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a sharp decline in cases5,6 and there appeared to be a change in the seasonality of the causative viruses during periods of high incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection.7,10–13 No large studies have been published, and it is still unknown if the observed effect has been maintained. The available evidence derives from countries with varying climatic conditions and healthcare structures.4,7–10

Our findings underline the implications of these changes in routine clinical practice,9 and provide data that are essential for effective outbreak prevention and control strategies.

Our main objective was to analyze the epidemiology of acute bronchiolitis during the pandemic, to compare it with previous seasons, and to examine other factors, such as severity of episodes, respiratory support, hospital stay, risk factors, and etiology. To this end, we designed an observational retrospective cohort study in patients hospitalized for acute bronchiolitis in the Hospital Virgen del Rocío over 4 epidemiological seasons, and conducted a descriptive and a bivariate analysis between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

The study was submitted to the relevant ethics committee for approval prior to initiation.

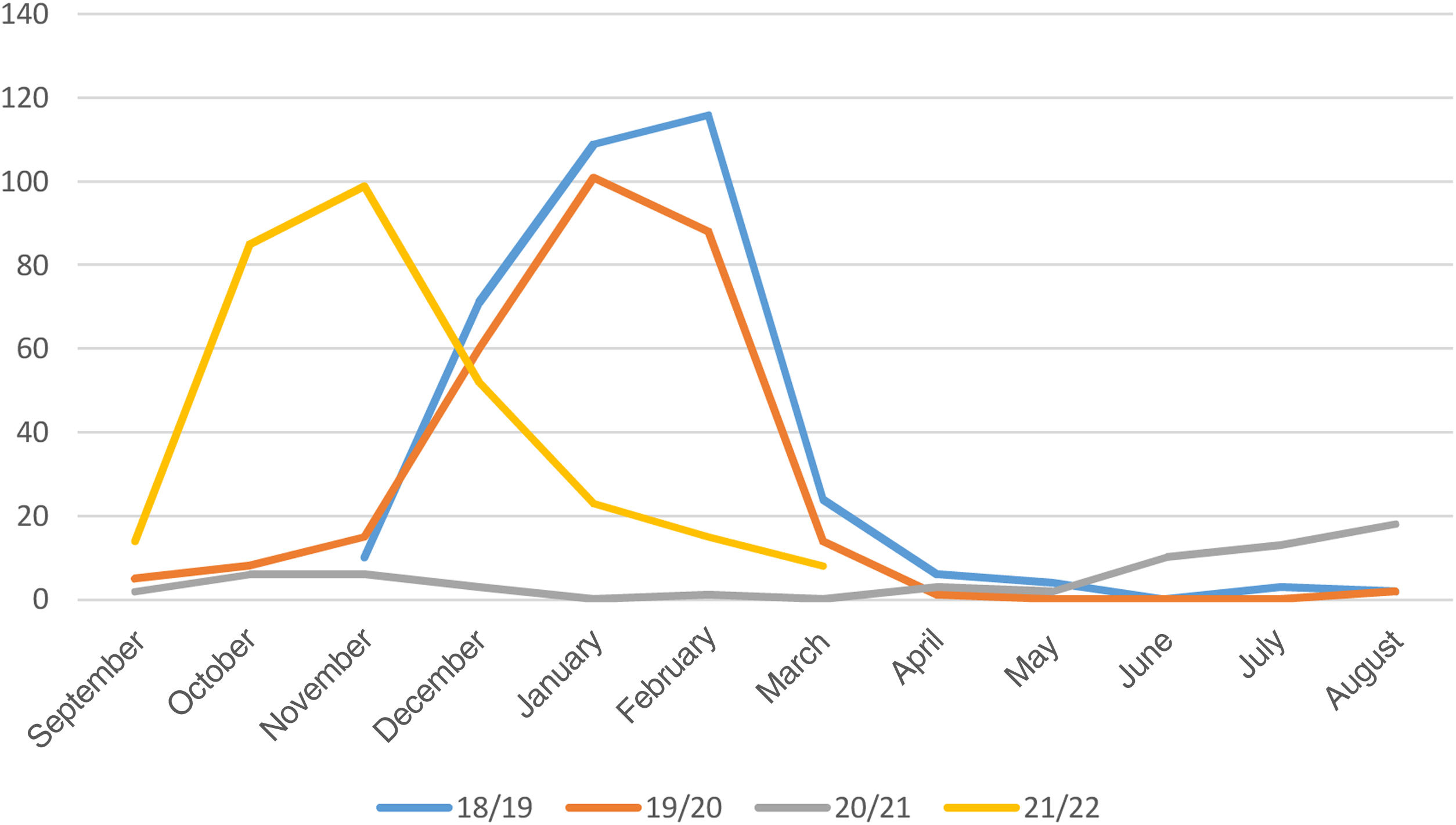

A total of 916 patients met the study inclusion criteria. During the pre-pandemic period, 549 patients were admitted, with a mean of 274 per season. Each season began in October and ended in March or April, with a peak observed during January or February (Fig. 1).

Our study shows a change in the seasonal pattern of acute bronchiolitis during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a drastic 76.64% reduction in cases during the autumn–winter of 2020–2021 (Fig. 1). These figures are similar to those reported in other countries.12,14–16

Infections also peaked during the summer of 2021 and in October–November of the same year, several months earlier than in previous seasons3 (Fig. 1).

The increased demand for healthcare during these peaks has a high socioeconomic impact can overwhelm health systems.17,18 Acute bronchiolitis alone generates 1.5 million visits to primary care centers each year, and accounts for around 3 million absentee days to care for a sick child.18

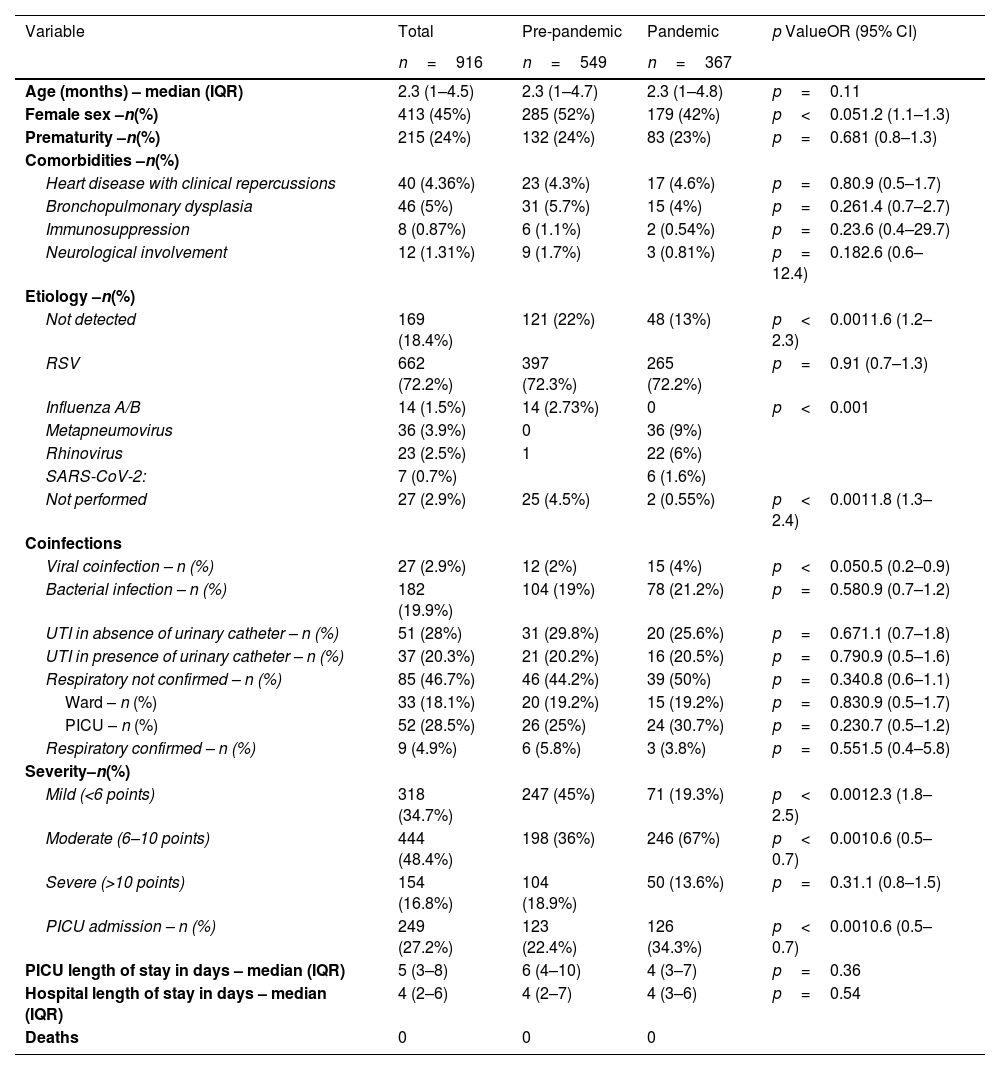

We observed a higher number of admissions to the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) during the pandemic, along with a greater use of non-invasive mechanical ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy, procedures that are more aggressive than nasal cannulas. This period also saw the lowest number of mild cases of acute bronchiolitis and the highest number of moderate cases, while both moderate and severe cases accounted for ICU admissions. No differences were observed with respect to total hospital stay and ICU stay (Table 1).

Main Patient Characteristics.

| Variable | Total | Pre-pandemic | Pandemic | p ValueOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=916 | n=549 | n=367 | ||

| Age (months) – median (IQR) | 2.3 (1–4.5) | 2.3 (1–4.7) | 2.3 (1–4.8) | p=0.11 |

| Female sex –n(%) | 413 (45%) | 285 (52%) | 179 (42%) | p<0.051.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Prematurity –n(%) | 215 (24%) | 132 (24%) | 83 (23%) | p=0.681 (0.8–1.3) |

| Comorbidities –n(%) | ||||

| Heart disease with clinical repercussions | 40 (4.36%) | 23 (4.3%) | 17 (4.6%) | p=0.80.9 (0.5–1.7) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 46 (5%) | 31 (5.7%) | 15 (4%) | p=0.261.4 (0.7–2.7) |

| Immunosuppression | 8 (0.87%) | 6 (1.1%) | 2 (0.54%) | p=0.23.6 (0.4–29.7) |

| Neurological involvement | 12 (1.31%) | 9 (1.7%) | 3 (0.81%) | p=0.182.6 (0.6–12.4) |

| Etiology –n(%) | ||||

| Not detected | 169 (18.4%) | 121 (22%) | 48 (13%) | p<0.0011.6 (1.2–2.3) |

| RSV | 662 (72.2%) | 397 (72.3%) | 265 (72.2%) | p=0.91 (0.7–1.3) |

| Influenza A/B | 14 (1.5%) | 14 (2.73%) | 0 | p<0.001 |

| Metapneumovirus | 36 (3.9%) | 0 | 36 (9%) | |

| Rhinovirus | 23 (2.5%) | 1 | 22 (6%) | |

| SARS-CoV-2: | 7 (0.7%) | 6 (1.6%) | ||

| Not performed | 27 (2.9%) | 25 (4.5%) | 2 (0.55%) | p<0.0011.8 (1.3–2.4) |

| Coinfections | ||||

| Viral coinfection – n (%) | 27 (2.9%) | 12 (2%) | 15 (4%) | p<0.050.5 (0.2–0.9) |

| Bacterial infection – n (%) | 182 (19.9%) | 104 (19%) | 78 (21.2%) | p=0.580.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| UTI in absence of urinary catheter – n (%) | 51 (28%) | 31 (29.8%) | 20 (25.6%) | p=0.671.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| UTI in presence of urinary catheter – n (%) | 37 (20.3%) | 21 (20.2%) | 16 (20.5%) | p=0.790.9 (0.5–1.6) |

| Respiratory not confirmed – n (%) | 85 (46.7%) | 46 (44.2%) | 39 (50%) | p=0.340.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| Ward – n (%) | 33 (18.1%) | 20 (19.2%) | 15 (19.2%) | p=0.830.9 (0.5–1.7) |

| PICU – n (%) | 52 (28.5%) | 26 (25%) | 24 (30.7%) | p=0.230.7 (0.5–1.2) |

| Respiratory confirmed – n (%) | 9 (4.9%) | 6 (5.8%) | 3 (3.8%) | p=0.551.5 (0.4–5.8) |

| Severity–n(%) | ||||

| Mild (<6 points) | 318 (34.7%) | 247 (45%) | 71 (19.3%) | p<0.0012.3 (1.8–2.5) |

| Moderate (6–10 points) | 444 (48.4%) | 198 (36%) | 246 (67%) | p<0.0010.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| Severe (>10 points) | 154 (16.8%) | 104 (18.9%) | 50 (13.6%) | p=0.31.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| PICU admission – n (%) | 249 (27.2%) | 123 (22.4%) | 126 (34.3%) | p<0.0010.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| PICU length of stay in days – median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 6 (4–10) | 4 (3–7) | p=0.36 |

| Hospital length of stay in days – median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (3–6) | p=0.54 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

The increase in ICU admissions could have been due to isolation measures and a reluctance to attend healthcare facilities, to the extent that mild cases either went untreated or were managed in primary care.

An analysis of the baseline characteristics of the sample revealed no significant differences, suggesting that although the number of cases fell, patient characteristics remained unchanged. No 28-day deaths were recorded in any of the study periods (Table 1).

The most frequent etiological agent in all seasons, in line with the literature,2,3,10–13 was RSV. During the pandemic, no influenza infections were reported (Table 1), perhaps due to the ecological niche theory discussed below. During the 2020/2021 season, the incidence of influenza was very low worldwide, and in Spain in particular.

Rhinovirus, detected in 23 cases, is associated with a risk of recurrent wheezing, and, according to some studies,19 this risk can be reduced with corticosteroid therapy.

Once new detection methods became available, viral coinfections were also found to be more frequent during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Differences in the number of patients admitted for whom no screening test was performed (Table 1) may be due to the higher rate of admissions in the pre-pandemic seasons when the hospital was overwhelmed and unable to fully meet healthcare demands, or to the need to identify the etiological agent in order to take the appropriate isolation measures required during the 2-year pandemic that had such a crushing impact on public health systems.

Although SARS-CoV-2 can cause bronchiolitis, a multicenter study of children hospitalized with SARS-CoV-220 concluded that SARS-CoV-2 infection does not appear to be a major trigger for severe bronchiolitis and should be managed according to the usual guidelines, generally without requiring hospital admission. This is in keeping with our study, in which only 1 patient was admitted to the ICU with this etiology. Indeed, the probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children is similar to that of adults, and they remain largely asymptomatic.20

These results may have a significant impact on clinical practice.

It is essential to maintain epidemiological surveillance systems that issue alerts on epidemiological variations in the pattern of circulating viruses, since changes in seasonality may involve redistributing material and human resources and implementing immunoprophylaxis strategies to protect risk groups. This factor should be corroborated in subsequent seasons.12

We also need to recognize that the measures imposed during the pandemic played a key role in significantly reducing the number of respiratory infections9; this knowledge can help us effectively plan future prevention strategies in at-risk populations.

Evidence that the relaxation of social restrictions in the spring of 2021 in Spain coincided with the re-emergence of acute bronchiolitis would support this hypothesis.

Aside from isolation measures, other theories have also been proposed to explain this situation, such as the ecological niche – namely, the role played by pathogens in the ecosystem in response to the existence or absence of other microorganisms and climatic conditions.

Thus, the outbreak of COVID-19 may have displaced other pathogens such as RSV, given the steady decline in the prevalence of RSV infections and the increase in the number of influenza cases. Our study shows, however, that RSV can co-exist with other pathogens.

According to this hypothesis, the reduction in circulating levels of SARS-CoV-2 at the time COVID-19 confinement measures were relaxed could have played a fundamental role in the upturn of RSV cases.

The literature indicates that RSV epidemics are generally associated with the cold and damp of autumn and winter, suggesting that high rates of infection are unlikely outside these periods.2,3 However, this is refuted by our study, since we recorded epidemic rates of infections in the Hospital Virgen del Rocío in Seville during the month of October, at a time when the climate is still hot and dry.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.