Blunt chest trauma is a rare cause of acquired benign airway stenosis. Only 0.4–1.5% of these events induce airway injury, which mostly occurs in the right main bronchus and within 2cm of the tracheal carina.1 Half of all airway injuries are not identified during the first 24–48h, because normal ventilation may be present despite the airway injury and because of non-specific symptoms and other injuries, such as head trauma, abdominal injuries, and multiple extremity fractures.1 If airway injuries are not recognized early, an aberrant airway healing process can lead to the formation of granulation tissue and collagen deposition and, ultimately, to delayed tracheobronchial stenosis.2 Although delayed tracheobronchial stenosis after blunt chest trauma is treated with bronchoscopic intervention (e.g., balloon dilation, laser ablation, and airway stents), surgical intervention, or a combination of these methods, no treatment consensus or guidelines have been established for this condition.2,3 The management of delayed tracheobronchial stenosis caused by blunt chest trauma highly depends on patient status, severity of symptoms, location and extent of stenosis, degree of distal pulmonary parenchymal destruction, and local expertise.2 Here, we describe the case of a patient with delayed right main bronchus stenosis involving the tracheal carina after blunt chest trauma who was successfully treated with tracheobronchial anastomosis.

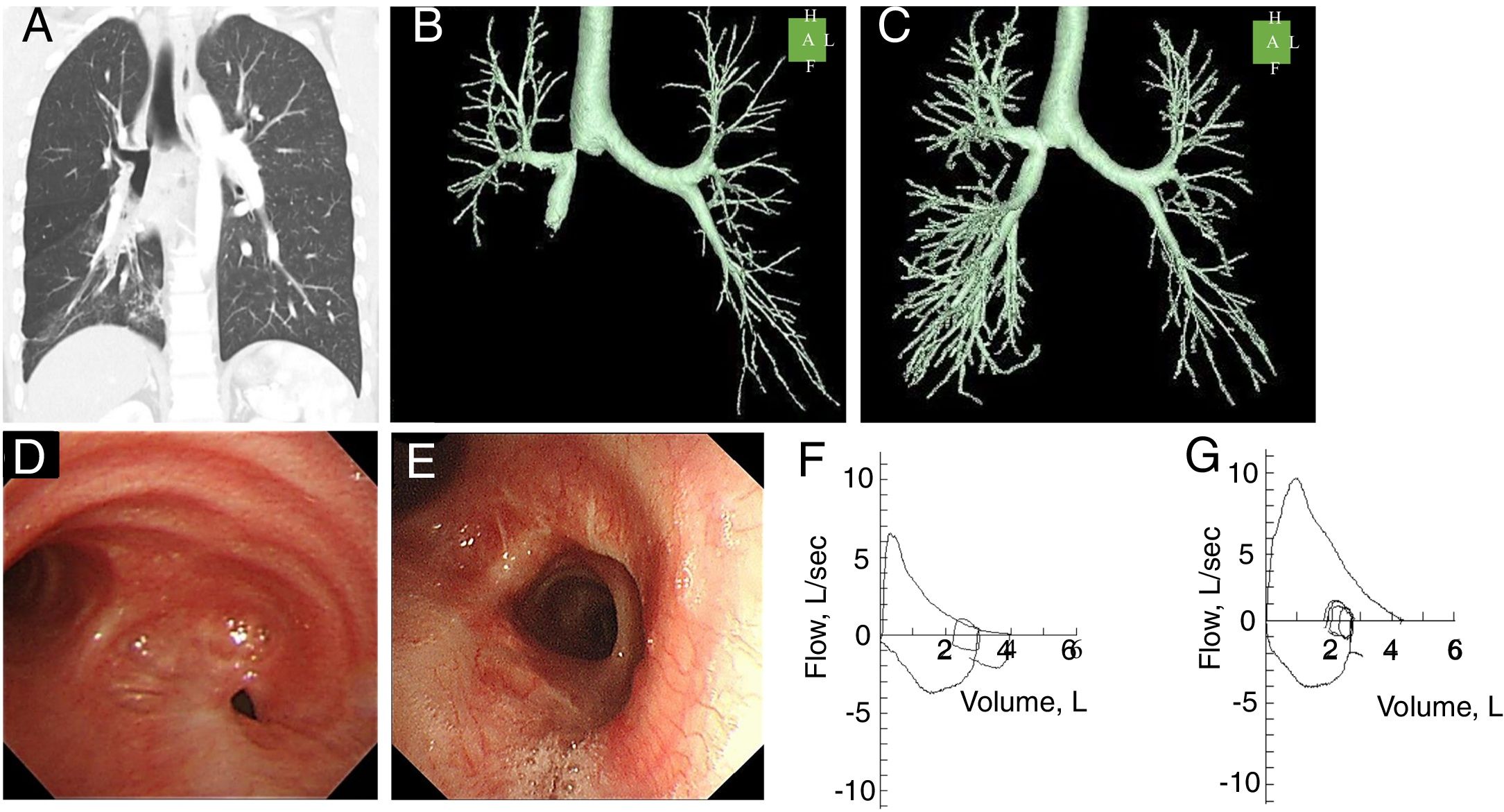

A 34-year old male current smoker had been involved in a motor vehicle accident at the age of 21. He suffered bilateral pneumothorax, which was treated only with chest drainage tubes. The patient developed pneumonia every 12 years starting at the age of 24. During the pneumonia episodes, he complained of wheezing and dyspnea. The patient did not have any lower respiratory tract infections during childhood. Recently, he started having recurrent obstructive pneumonia every 12 months, which led him to visit the Department of Respiratory Medicine of the local hospital. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed ground grass opacity and consolidation in the right middle and lower lobes, and bronchial mucous retention with stenosis of the right main bronchus, the length of which was less than 1cm (Fig. 1A, B). Flexible fiber-optic bronchoscopy (FOB) showed a fibrotic lesion causing almost complete stenosis of the proximal right main bronchus, with the exception of a pinhole located at the lateral posterior aspect of the stenosis (Fig. 1D). His forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC ratio, expiratory reserve volume (ERV), and residual volume (RV)/total lung capacity (TLC) ratio, were 92.4% (4.23L), 61.4% (2.47L), 58.39%, 76.8% (1.29L), and 32.13%, respectively (Fig. 1F).

Coronal chest CT image (A) and three-dimensional chest CT image (B) acquired before the operation and three-dimensional chest CT image acquired 3 months after the operation (C). Flexible fiber-optic bronchoscopic images before the operation (D) and 3 months after the operation (E). Flow-volume loops before the operation (F) and 3 months after the operation (G).

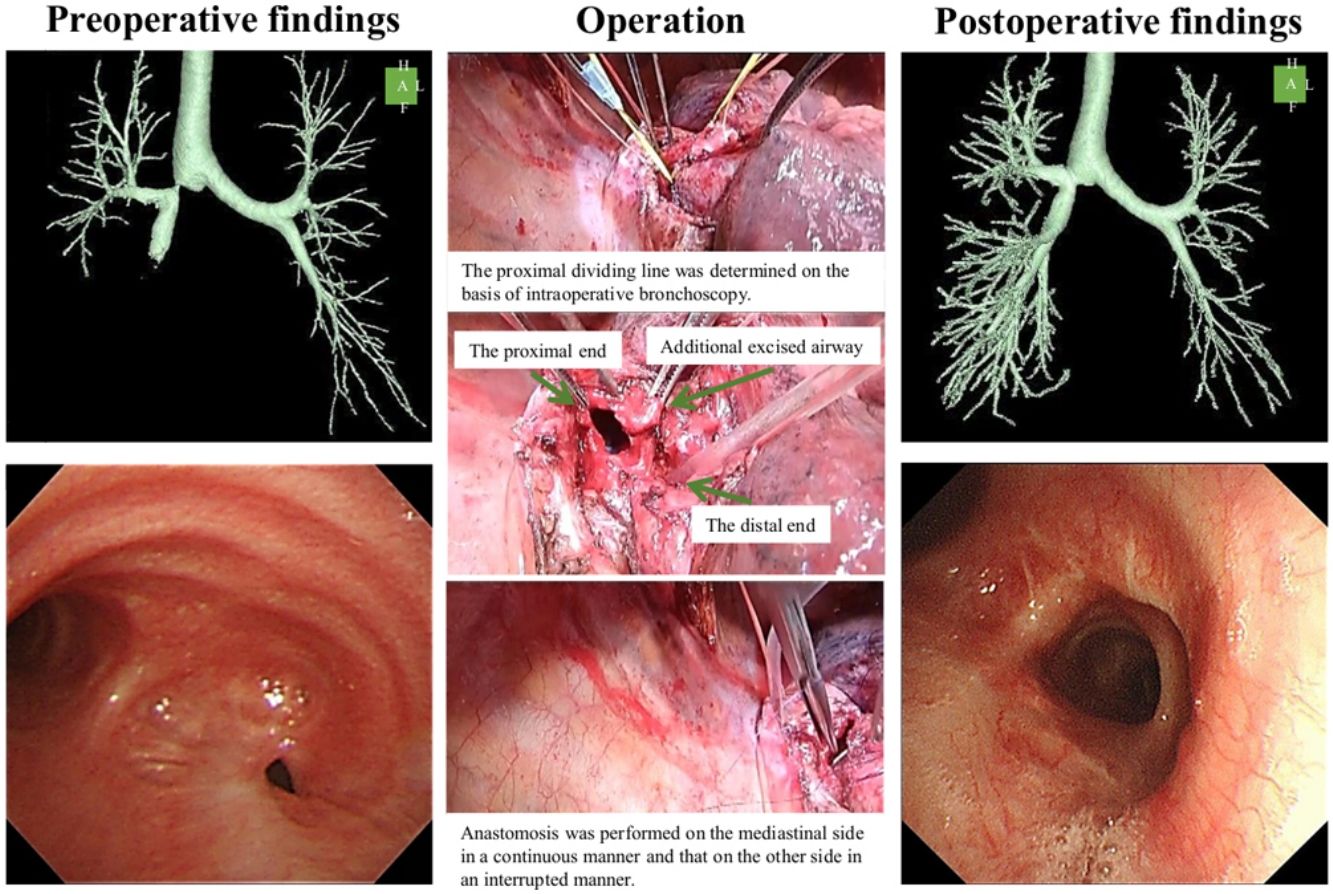

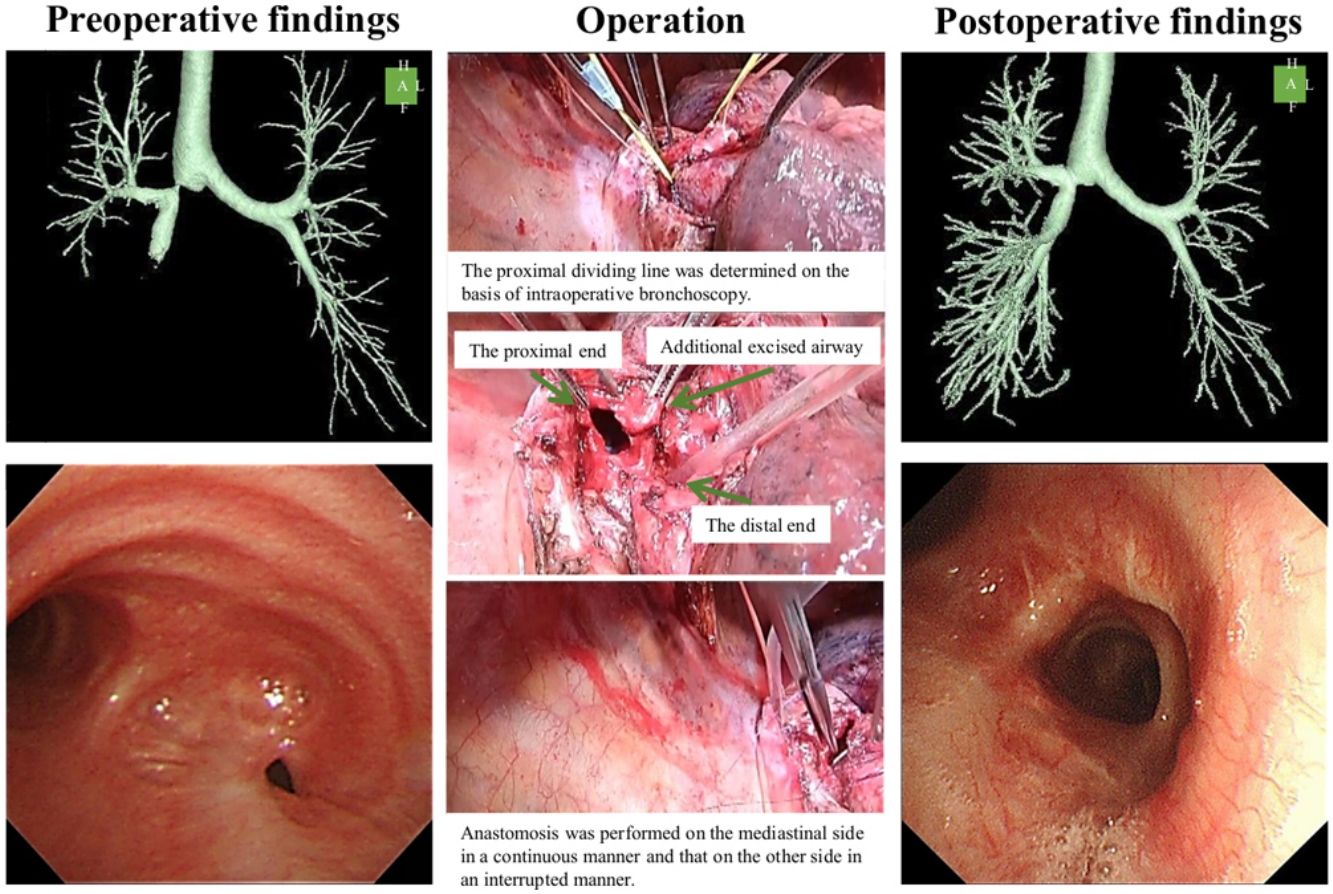

The patient was referred to our hospital for treatment of the right main bronchus stenosis. We selected surgical intervention (supplemental video). Under general single-lung ventilation with a double-lumen tube, we performed a right posterolateral thoracotomy and found that the lung had adhered to the chest wall and that the middle and lower lobes showed consolidation. We opened the right main bronchus at the proximal side; however, the stenosis remained, and we resected half of the tracheal carina and the lower part of the trachea. At the distal side, the main bronchus was removed to the smallest extent possible, which was approximately 2cm. Anastomosis was performed with continuous suture for the mediastinal side and interrupted suture for the other part using 4-0 polydioxanone suture, and pedicled pericardial fat tissue was used as a cover. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 12 without any postoperative complications. Pathological analysis of the resected specimen showed the presence of granulation tissue with a focal fibrosis lesion and no evidence of malignancy.

Follow-up chest CT (Fig. 1C) and flexible FOB (Fig. 1E) performed 3 months postoperatively showed successful healing of the anastomosis with luminal patency. A follow-up pulmonary function test revealed improvement of the obstructive ventilatory defect based on FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, ERV, and RV/TLC ratio values of 101.3% (4.66L), 93.3% (3.77L), 80.9%, 98.8% (1.67L), and 27.6%, respectively (Fig. 1G). The patient did not develop pneumonia for 10 months after the operation.

If stenosis involves the tracheal carina, surgical intervention may be associated with an increased risk because of technical difficulties and a high level of postoperative complications, such as anastomotic dehiscence and restenosis.4,5 Two previous studies showed that delayed airway stenosis with involvement of the tracheal carina after blunt chest trauma was successfully treated with repeated balloon dilation and stent placement.6,7 Thus, it was considered that we should perform a bronchoscopic intervention; however, we decided on surgical intervention for the following reasons. First, we considered that we could perform tension-free anastomosis, because the stenotic lesion affected the main bronchus exclusively. Second, the stenosis did not induce the formation of a right lung abscess. Third, bronchoscopic treatments might require repeated interventions because of migration and formation of granulation and because of the recurrence of stenosis after stent removal.8 Forth, the patient was young and his preoperative condition was good. In the present case, surgical intervention was an acceptable method for managing stenosis involving the carina. Previous studies reported no perioperative mortality by surgical intervention for benign airway stenosis.9,10 Therefore, surgical intervention should be considered in the future under the same condition.

The median time from initial injury to diagnosis of delayed tracheobronchial stenosis is 6 months.2 Kiser et al. reported an absence of association between time to the diagnosis of delayed tracheobronchial stenosis and the rate of successful surgical repair.11 Perioperative complications related to surgical intervention for tracheobronchial stenosis includes empyema, rebleeding, stenosis, and fistula.2,12 The current patient was diagnosed 13 years after the initial motor vehicle accident and experienced no perioperative complications. The long-term complications or long-term follow-up outcomes are unknown12; therefore, we should carefully investigate the future disease profiles of this case.

Here, we successfully treated a case of delayed airway stenosis involving the tracheal carina with surgical intervention. As the treatment consensus or guidelines for delayed airway stenosis after blunt chest trauma have not been established, a very careful clinical and radiological evaluation is needed to prevent peri- and post-operative complications before deciding on whether to adapt this technique.

Financial conflictsThis study was funded in part by the JSPS KAKENHI 19K17634 (SH). The Department of Advanced Medicine for Respiratory Failure is a Department of Collaborative Research Laboratory funded by Teijin Pharma.

Conflict of interestSatoshi Hamada reports grants from Teijin Pharma, outside the submitted work.

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

Supplemental video: Posterolateral thoracotomy was performed via the fourth intercostal space. Intrapleural adhesions at the apex and the base were dissected. Then, the right main bronchus was dissected and encircled with a vessel tape. The bronchus intermedius was also dissected. Hilar release was performed with pericardiotomy around the inferior pulmonary vein. The proximal dividing line was determined on the basis of intraoperative bronchoscopy. The mediastinal side of the trachea and the mediastinal side of the right main bronchus were trimmed. Anastomosis was performed on the mediastinal side in a continuous manner and that on the other side in an interrupted manner. The sealing test was negative for air leak at the anastomosis site. The anastomosis was covered with a pericardial fat pad.