The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a far-reaching re-allocation of economic, social, and health resources that has affected the control, diagnosis, and prognosis of other diseases1–3. Tuberculosis (TB) control and prevention programs have also suffered from resources being diverted to efforts to control the pandemic4,5. The World Health Organization believes that 21% of people with tuberculosis remained undiagnosed in 2020, resulting in 500,000 more mortalities than the organization's own targets set out in its ‘End TB’ strategy6,7.

However, social distancing and respiratory isolation measures implemented since the outbreak of the pandemic have had a beneficial effect on the incidence of other infectious diseases transmitted via the respiratory route that have a short incubation period, such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and others8–11.

The impact of anti-COVID-19 measures on TB, a disease with a longer incubation period that is also transmitted by the respiratory route, is not sufficiently understood. In this study, we present data on the incidence of TB relative to the COVID-19 pandemic in Galicia, Spain, where there is a recognized and consolidated TB prevention and control program that includes active contact tracing12.

All cases of TB included in the Galician TB Registry between 2015 and 2020 were pooled for review on 7 May 2021. The following variables were analyzed: date of diagnosis, age, location, chest X-ray characteristics (cavitary/non-cavitary), sputum smear (bacilliferous/non-bacilliferous), source of case data (notification of the physician responsible for diagnosis, or active searches of microbiology and pathology records, Aids registries, penitentiary institution archives, and death records) and diagnostic delay since the onset of symptoms. Population data were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics registry. The incidence of TB in the last half of 2020 after implementation of confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic was compared with that of the same period in 2019 by comparison of proportions. Days of diagnostic delay were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Six-month trends since 2015 were analyzed using a Poisson regression analysis, followed by a segmented regression analysis to detect a possible point of significant change in the trend.

The study did not require Ethics Committee approval as it is a pooled data analysis and there is no possibility of identifying patients.

In the second half of 2020, 172 cases of TB were recorded, compared with 262 in the same period of 2019, corresponding to a 6-monthly incidence of 6.4 vs. 9.7 per 100,000 inhabitants (risk reduction=34.35%; 95% CI: 20.43–45.84). Case data were obtained from active searches in microbiology and other records in 34.3% (59/172) of cases in the second half of 2020 vs. 29.0% (76/262) in 2019 (p=0.29). The percentage of patients with forms of TB suggestive of greater diagnostic delay (patients with bacilliferous disease or cavitation on chest X-ray) was similar in both periods: 29.1% had bacilliferous disease in the second half of 2020 vs. 28.2% in the second half of 2019 (p=0.94); whereas the percentage of patients with cavitation on chest X-ray was 14.5% in the second half of 2020 vs. 17.2% in the same period of 2019 (p=0.55). The median diagnostic delay in the second half of 2020 was 60.5 days (IQR: 23.0–122.0) vs. 65 days (IQR: 30.5–121.5) in the same period of 2019 (p=0.51).

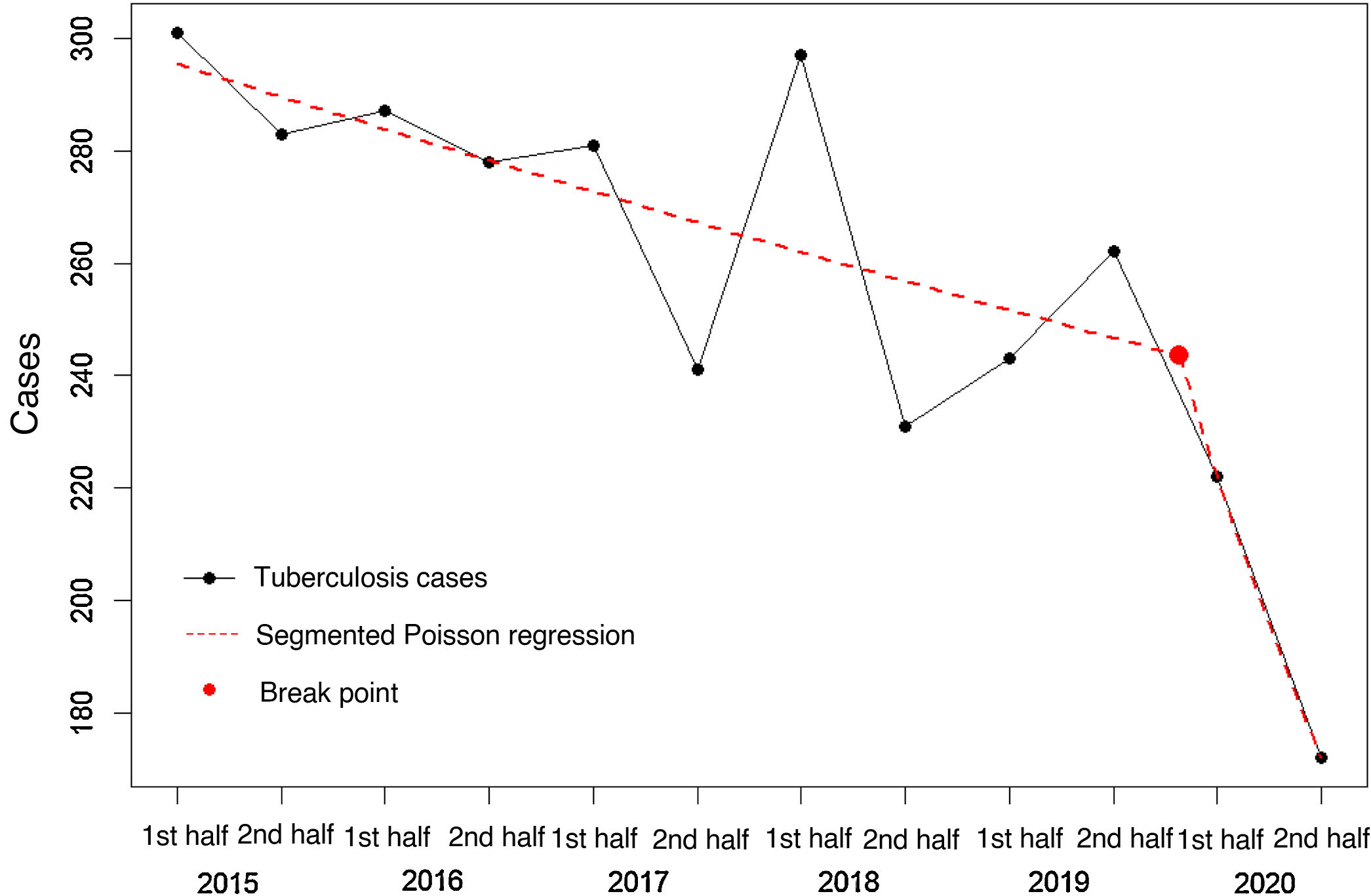

The analysis of 6-monthly trends revealed a 32% annual decrease in risk for the 2015–2020 period (95% CI 22–42%), a rate that is greater than the 20% decrease observed over the 2015–2019 period as a whole (95% CI 7–33%). The segmented Poisson regression analysis shows a break point in incidence after 2020 with a RR value of 0.980 (95% CI 0.967–0.993) for the initial part of the regression line (2015–2019), compared to a steeper decline in 2020 (RR=0.790; 95% CI 0.635–0.945) (Fig. 1).

A significant decrease was therefore observed in registered cases of TB following the introduction of preventive measures for COVID-19. This could be due to 3, not necessarily exclusive, factors. First, possible under-reporting of cases. Secondly, possible diagnostic delay caused by re-allocation of health resources (microbiology laboratories, primary care, and the TB programs themselves), difficulties in accessing oversaturated healthcare services, and/or reluctance to attend hospitals or health centers for fear of exposure to SARS-CoV-213,14.

Finally, there may be a real decline in TB cases associated with the reduction of respiratory-borne diseases following the introduction of confinement measures, social distancing, and use of masks15. We believe that this is the most realistic explanation in our autonomous community. Although some resources allocated to the TB control program in Galicia have been diverted, TB units have retained their basic structure and functions. Immediate care has been maintained for patients, contacts, screened patients, and patients with suspected TB diagnosis, while active contact tracing continues. There was no increase in the number of patients with advanced forms of the disease (bacilliferous, cavitation on X-ray) or in diagnostic delays in the second half of 2020, an observation that supports our hypothesis that the incidence of tuberculosis has actually decreased.

Although TB has hitherto been thought to manifest in only 50% of cases in the first 2 years of infection, recent evidence suggests that the incubation period is shorter in most cases16. This also supports the hypothesis of a real decline in TB, despite the short time since the start of isolation measures in March 2020. Studies conducted in other countries also describe a decrease in the incidence of TB, although they do not focus so closely on the impact of COVID-19 control measures17,18.

The development of the pandemic over time, the measures taken to control it, and the longer-term monitoring of TB incidence rates will definitively confirm the existence of a real decline in the incidence of TB associated with social isolation measures. Be that as it may, we agree with other authors that a possible decline in TB cases is no reason to relax disease control measures, but should rather serve as an incentive to reinforce vigilance19,20.

In conclusion, social distancing and respiratory isolation measures, including the widespread use of masks, contribute positively to the decrease in the incidence of TB in our environment.

A. Castro-Paz (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense); E. Cruz-Ferro (Programa gallego de tuberculosis. D.G. de Salud Pública); L. Ferreiro-Fernández (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago); M. Otero Santiago (Hospital Universitario de A Coruña); A. Penas Truque (Hospital Lucus Augusti de Lugo); M.L. Pérez del Molino (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago); A. Rodríguez-Canal (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense); J.A. Taboada Rodríguez (D. G. de Salud Pública); P. Valiño López (Hospital Universitario de A Coruña); E. Vázquez García-Serrano (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide de Ferrol); R. Zubizarreta Alberdi (D.G. de Salud Pública).