We report the case of a 57-year-old woman with a history of arterial hypertension, myasthenia gravis, thymectomy and left empyema.

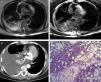

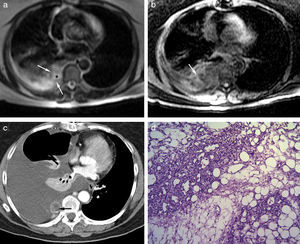

She was admitted with a 2-month history of dry cough and progressive dyspnea, and no other symptoms. Pulmonary auscultation revealed right basal hypoventilation; the examination was otherwise normal. Chest X-ray showed free pleural effusion in the right middle lung field. Clinical laboratory results showed moderate hypoxemia. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed submassive right pleural effusion, with secondary atelectasis; a solid mass over the paravertebral parietal pleura was observed, suggestive of tumor disease (Fig. 1). Thoracentesis was performed and a serofibrinous fluid was drained. This was considered exudate in view of the protein ratio of 0.8, although pH and glucose were normal and the leukocyte count was very low (140mm3). Adenosine deaminase levels were normal. Sputum smears and cultures were negative. Cytology revealed inflammation and reactive mesothelial hyperplasia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was normal. Positron emission tomography (PET) was negative for malignancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified a poorly delimited, heterogeneous paraspinal lesion, with no vertebral involvement. Possible pleural infiltration with a vascular component and pleural effusion was observed, the origin of which was located in the paraspinal white tissue or parietal pleura (Fig. 1). Rapid pleural filling required frequent drainage by thoracentesis. Finally, video-assisted thoracoscopy was performed and a solid paravertebral and intravertebral tumor was resected. Gross examination revealed an uneven, purplish 4cm×2cm×2cm tumor with hemorrhagic areas, partially enveloped in pleura. It was identified microscopically as a fragment of parietal pleura, with transmural thickening as a result of a poorly delimited, unencapsulated solid tumor, consisting of mature adipocytes intermixed with abundant vessels of varying sizes, and no endothelial cell atypia. The mesothelial sheath showed mild hyperplastic reactive changes (Fig. 1d). Immunohistochemistry showed: CD-34, CD-31 and factor VIII: intense, diffuse positivity in the vascular areas; calretinin, pankeratin, and Ck 5/6: positivity in the mesothelial sheath; Ki57: low proliferative index (<3%). The definitive diagnosis was mesenchymal tumor, consistent with paravertebral chest wall angiolipoma. One year after resection and talc pleurodesis, the patient remains without relapse.

(a) Chest magnetic resonance imaging, T2-weighted axial sequence showing heterogeneous lesion with hyperintense foci due to fluid cavities or fat (*) and hypointense linear images, due to septa or vessels (arrows); (b) Spoiled gradient-echo T1-weighted axial sequence with fat suppression and early-phase paramagnetic contrast medium (intravenous gadolinium): heterogeneous mass with enhancement of some of the serpiginous images (arrow); (c) computed tomography with intravenous contrast medium: heterogeneous lobulated mass, showing reticular and linear enhancement, with small hypodense foci (arrow), compatible with fat; and (d) solid tumor consisting of mature adipose tissue associated with a network of thin-walled, anastomated blood vessels. Red blood cells are seen in most of the vessels (hematoxylin & eosin ×100).

Angiolipomas are benign tumors, generally located under the skin, most often in the trunk or the limbs, although they have very occasionally been described in the thoracic cavity.1 This is the first report of an intrapleural location with associated effusion. In anatomical pathology terms, these tumors are formed of mature adipocytes and numerous vessels in varying proportions.2 They tend to appear benign on PET imaging.3 CT may reveal heterogeneity with areas of fat attenuation and enhancement in vascular areas, but differences in the ratios of each type of tissue make it difficult to make an accurate diagnosis. Differential diagnoses to consider include infiltrating hemangioma, neuroendocrine tumors, or other mesenchymal tumors. In view of the difficulty of achieving diagnosis before surgery, MRI may be the gold standard imaging test, as it reveals isointense images in T1 (lipomatous component) and hyperintense images in T2 (vascular component).4

We thank Dr José Antonio Fernández Gómez for his collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Santolaria MA, Teller P, Muñoz G. Angiolipoma torácico: el riesgo de ser original. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:171–172.