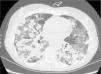

We report the case of a 57-year-old woman, former smoker, with a history of non-pathological cervical and axillary lymphadenopathies, non-necrotizing granulomatous mastitis and acute dorsal myelopathy. She was admitted for bronchopneumonia, and underwent bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies, which were inconclusive, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showing 65% lymphocytes and a normal CD4/CD8 ratio. The patient was readmitted due to right pleural effusion, categorized as lymphocytic exudate with no malignant cellularity, hepatosplenomegaly, and signs of pulmonary hypertension. Low levels of IgG subclasses were reported and treatment was initiated with prednisone. The patient subsequently developed dyspnea, anorexia and asthenia. Chest computed tomography showed peribronchial pulmonary nodules with undefined borders, air bronchogram sign, and tendency to converge into large masses in the lower lobes. These masses were surrounded by ground glass opacities and mediastinal lymphadenopathies, indicative of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Ground glass opacities and lymphadenopathies, however, are not typical of lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and may have been associated with the patient's smoking habit (Fig. 1). Lung function tests showed moderate restriction, with 36% diffusion, and laboratory reports revealed leukopenia due to lymphopenia. A bone marrow biopsy and a second bronchoscopy were performed, from which BAL showed predominant lymphocytes and a normal CD4/CD8 ratio. No additional data could be obtained from biopsy of a paratracheal lymphadenopathy. Culture and cytology were negative. A lung biopsy was obtained, after which the patient showed clinical and radiological worsening.

The result of the bone marrow biopsy suggested a T-cell-rich large-B-cell lymphoma. Chemotherapy was initiated, without improvement. Pathology results from the lung biopsy were inconclusive. The patient continued to worsen rapidly and progressively until she died. Autopsy confirmed diffuse T-cell and histiocyte-rich large-B-cell lymphoma, associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), with perivascular involvement and changes indicative of lymphomatoid granulomatosis.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis was first described in 1972 by Liebow et al.1 It occurs primarily in patients aged between 40 and 60 years, and mainly in men (2:1). It is an angiocentric and angiodestructive process, affecting extranodal regions that in 90% of cases involves the lung. This disease of the B-cells is thought to be associated with EBV infection, large-B-cell lymphoma, and immunosuppressive states.2 Typical lung involvement is characterized by nodular lesions, with lymphocytic invasion of the blood vessels, that may converge and cavitate.2,3 It is diagnosed from histology findings, including polymorphic lymphoid infiltrates, transmural infiltration of the arteries and veins by lymphoid cells, and focal areas of necrosis.4

The treatment of lymphomatoid granulomatosis is controversial, and varies according to the histological grade. In the absence of symptoms and if the histological grade is low, the patient should be monitored. Other cases are treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide, although standard therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma has also been attempted.

Satisfactory therapeutic outcomes have recently been achieved with interferon-alfa-2b and rituximab.5 The prognosis of lymphomatoid granulomatosis varies: spontaneous remission is observed in 20% of cases, while in others, mean survival is 2 years, with a 5-year mortality of 63%–90%.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Deltoro A, Lara SH, Calle SM. Granulomatosis linfomatoide: afectación pulmonar. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:605–606.