We present a 24-year-old male smoker of 1 pack/day with occasional vaping since 18 years, the last time being five days before coming to hospital with fever, odynophagia, headache, cough and frank hemoptysis. After a couple of hours under observation, he began to desaturate and presented new hemoptoic sputum, for which he was admitted to the ICU.

The examination revealed hypertension of 160/100mmHg and symmetrical pulmonary auscultation. Laboratory tests showed only a slight increase in CRP, 98mg/dL. SARS-Cov-2 PCR test was negative.

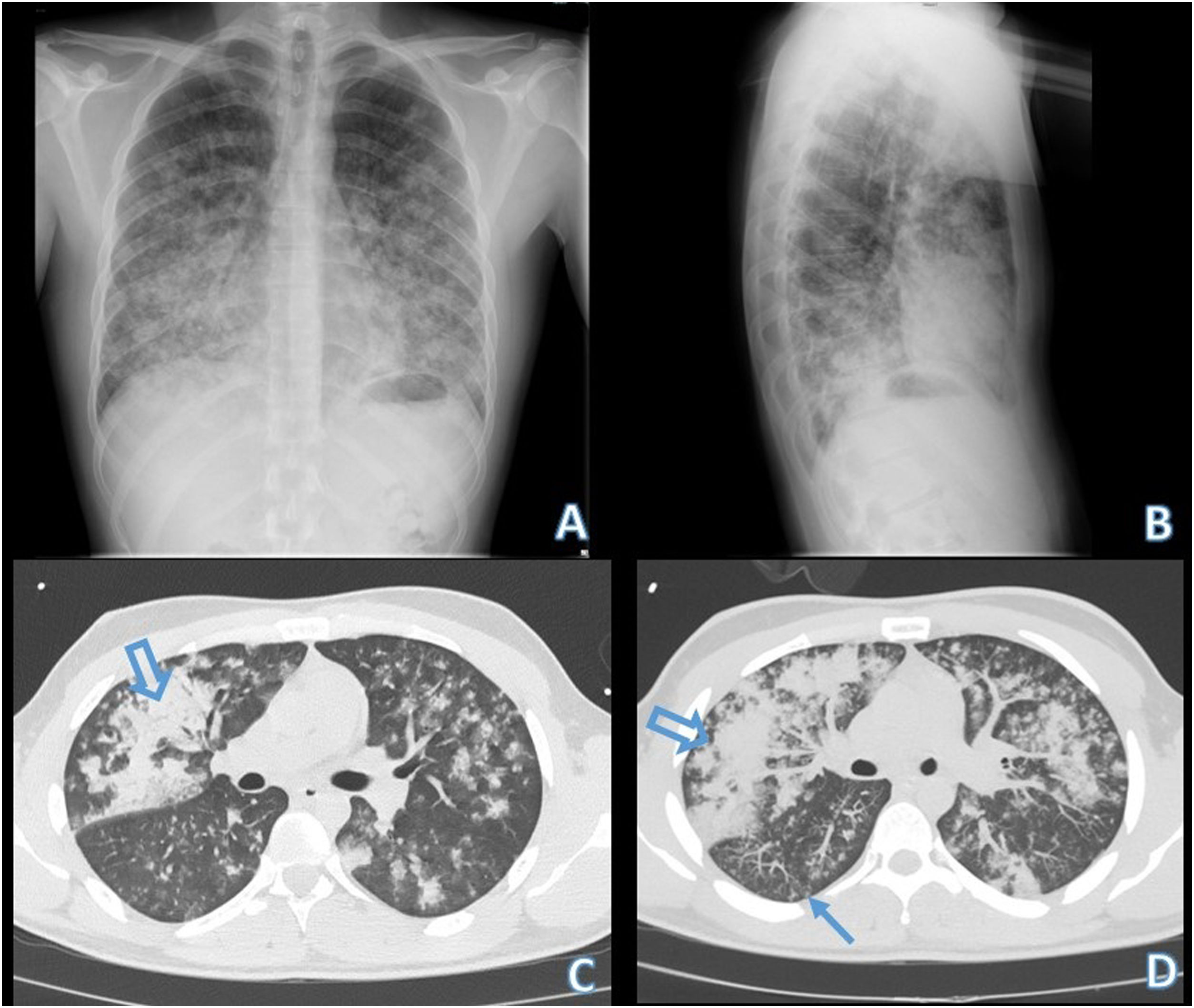

The chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltrates (Fig. 1A and B), so a chest CT scan was requested. In this test, patchy pulmonary opacities centered on centrilobular bronchioles were visualized, which become confluent forming alveolar parenchymal consolidations with air bronchogram, together with centrilobular nodules and “tree in bud” images (Fig. 1C and D).

Simple chest X-ray in AP (A) and lateral (B) projections, showing bilateral domain infiltrates in the middle and lower lung fields. Chest CT without IV contrast, lung parenchyma window and axial slices (C and D). We identify patchy pulmonary opacities centered on centrilobular bronchioles, which become confluent forming alveolar parenchymal consolidations with air bronchogram, diffusely distributed in both hemithorax although with dominance in the middle and lower lungs fields. In some areas, centrilobular nodules and “tree-in-bud” images are observed (thin arrow).

After bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (79% macrophages, 15% lymphocytes, 5% neutrophils, 1% eosinophils and appearance of frankly hematic fluid that prevented a good fresh cytological count), negative microbiological and urine toxic studies (Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and other Mycobacterium spp. Negative Legionella and Pneumococcus in urine and negative toxics like cannabis, amphetamine, cocaine and ecstasy MDMA), together with a history of recent vaping and imaging test findings, he was diagnosed with electronic cigarette associated lung disease (EVALI). Empirical antibiotic therapy was started, adding boluses of intravenous methylprednisolone 250mg, with a good response and discharge ten days after admission.

After a new visit to the Pneumology Department two months after admission, and the absence of inhalation of toxins, the patient reflected a very good general condition with chest X-ray without infiltrates.

The outbreak of a vaping-related respiratory illness was widely recognized in late 2019, although awareness of lung injury was noted in scattered reports prior to this year, particularly as use of vaping products was increasing among younger people.1,2 This is why the average age in recent studies was 21–24 years, and men were the most commonly affected.3

Respiratory complaints (97%),2,3 including shortness of breath and chest pain, are present in the majority of EVALI patients, and constitutional symptoms resembling viral illnesses are common.3,4 Interestingly, gastrointestinal disorders are also frequently observed (77%).2,3

Regarding its diagnostic imaging, the first reports suggested that a variety of pathological patterns of injury and inflammation could be found in EVALI, including: diffuse alveolar damage, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, mild nonspecific inflammation, granulomatous pneumonitis, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, and respiratory bronchiolitis.1,5 The typical findings on the EVALI chest radiograph are diffuse ground glass bilateral opacities with occasional subpleural sparing. Involvement of all lung lobes can be seen, but it is not universal.5

The confirmation diagnostic criteria proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2019 are the following (all four must be met): (a) use an electronic cigarette (“vape”) during the 90 days before symptoms; (b) pulmonary infiltrate, such as opacities on plain chest radiograph or ground-glass opacities on chest computed tomography; (c) absence of pulmonary infection in the initial study; (d) no alternative plausible diagnoses (e.g., cardiac, rheumatologic, or neoplastic process).5

On the other hand, bronchoscopy has been used, but cellular analysis has little diagnostic utility since there is no specific cellular pattern in EVALI, although it has been seen that a common finding is lipid-laden macrophages.5

Currently, there is no optimal treatment regimen for EVALI, however, as a first item, vaping should cease. Empirical antibiotic therapy is normally used to cover the main microorganisms that cause respiratory infections, but observational studies have shown clinical improvement in response to corticosteroids.5

EVALI is a serious lung disease with public health implications given the increased use of these “apparently” harmless e-cigarettes. Its diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion and exclusion of other possible causes of lung disease, which is why a thorough and complete clinical history is required and a collaboration between various services such as Pneumology, Radiology and Pathology.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.