Various metals have been described as causing occupational asthma (OA), mostly chromium, nickel, and cobalt. The mechanism of action by which these metals can produce OA is generally immunological, either IgE-mediated or not.1,2 To date, only 2 cases of OA caused by zinc have been described, and in both cases, an IgE-dependent mechanism was involved in the pathogenesis of the disorder.3,4

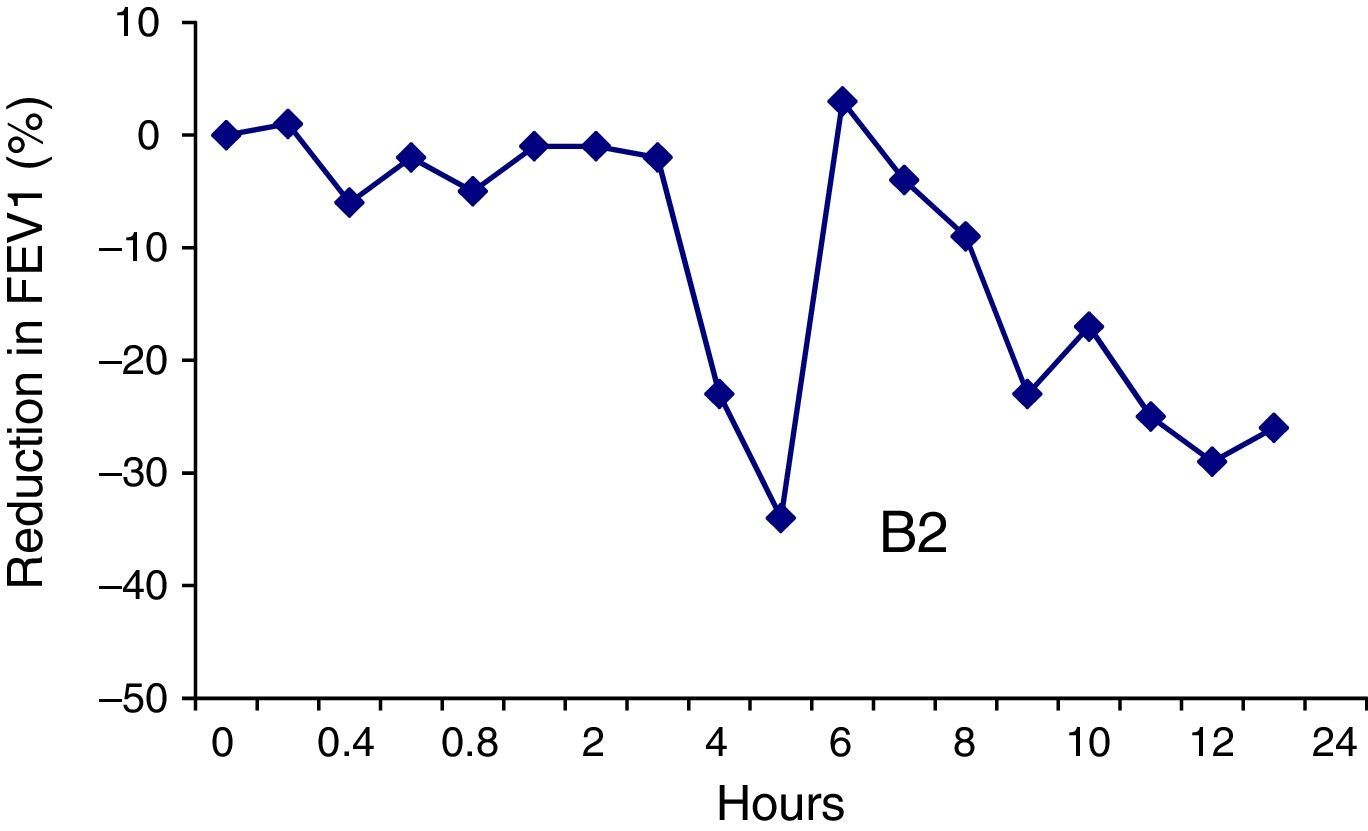

We describe, for the first time, a worker exposed to zinc who developed OA via a non-IgE-mediated immunological mechanism. Our patient was a 30-year-old man, former smoker of 5 pack-years, whose only clinical history consisted of a diagnosis of bronchial asthma in childhood, which had remitted, and for which he had not required treatment for 15 years. He had been working for 4 years as an industrial mechanic, making metal parts, and was in regular contact with copper, cadmium, zinc, and manganese dust. The patient consulted due to a 5-month history of cough, expectoration, wheezing, and dyspnea. Symptoms appeared some time after start of exposure and improved during the weekends and periods of sick leave. He had had to attend the emergency department on 5 occasions since the onset of symptoms. Chest radiograph was normal. Clinical laboratory tests showed a total IgE of 140kU/l. Skin tests for airborne allergens were positive for house dust mites, while contact skin tests for metal, including nickel sulfate, potassium dichromate, cadmium, cobalt chloride, and zinc 2.5%, were negative. Forced spirometry showed FVC 6360ml (112%), FEV1 4390ml (98%), and FEV1/FVC 69%. A methacholine challenge was positive with a PC20 of 4mg/ml. A provocation test was performed, according to standard methodology for testing metals,1,5 for which concentrations of 0.1mg/ml, 1mg/ml, and 10mg/ml of zinc sulfate were prepared. The 0.1mg/ml solution was nebulized for a total of 5min, split into periods of 1, 2, and 2min. Four hours after exposure, a 23% reduction in FEV1 from baseline was observed (Fig. 1), along with cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. These symptoms abated after administration of a ß2 agonist. Ten hours after exposure, the patient presented the same symptoms, with a 29% reduction in FEV1, requiring administration of intravenous corticosteroids in addition to ß2 agonist, and a 12-h stay in the emergency department.

Clinical and lung function data suggested that the patient had zinc-related OA, mediated by a non-IgE-dependent immunological mechanism. This diagnosis was supported by the latency period before the onset of symptoms after initiation of exposure, late onset of symptoms during the working day, the negative specific IgE test and skin tests, and the late reaction after the provocation test. Indeed, 2 recent studies have shown that low molecular weight agents are usually associated with late-onset reactions in which, although the immunological mechanisms are unclear, a non-IgE-dependent immunological mechanism is likely if no early or dual reaction is observed.6,7

Currently, OA is classified as immunological and non-immunological or irritant-induced, the most representative form being reactive airways dysfunction syndrome.8 Immunological OA is further subdivided into IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated, depending on its physiopathological origin.9 Although low molecular weight agents can cause immunological OA by both mechanisms, the IgE-mediated mechanism is generally exceptional, while a non-IgE-mediated mechanism is more common; this is the case with isocyanates and persulfates.10 However, the situation appears to differ when OA is caused by exposure to metals, in which some authors report that a non-IgE-mediated mechanism is observed in only 30%–40% of patients.1 In the specific case of zinc, the 2 cases reported to date suggested an IgE-mediated mechanism, as an early response was observed in the specific bronchial provocation test (SBPT), with a reduction in FEV1 of 23% and 28% 10 and 20min after inhalation, respectively.3,4 In this context, our observation supports the notion that, while there is no evidence of zinc sensitization, it must be considered as a possible causative agent of OA, and this diagnosis must not be ruled out. It is also important to mention that the presence of asthma before the occupational exposure, such as the childhood asthma reported by our patient, does not exclude the OA diagnosis, if the presence of an immunological mechanism (IgE or otherwise) is shown between exposure to the causative agent and the patient's asthma.11 In our case, this mechanism was confirmed by the provocation test.

It is also interesting to note that the patient's asthma presented clinically as severe, reflected by his attending the emergency department on 5 occasions during the 5-month period between the onset of asthma and diagnosis. The severe asthmatic reaction presented by the patient during the provocation test, requiring him to remain in the emergency department for 12h, is also remarkable. Moreover, this reaction occurred after exposure to 0.1mg/ml of zinc sulfate, a concentration not previously associated with severe asthmatic reactions in provocation tests with metals.5,12–14 In the 2 cases of OA caused by zinc reported to date, the reaction occurred when doses of 1 and 10mg/ml, respectively were used, and no severe reactions were observed.3,4 This observation is in line with the evidence of Meca et al.7 who suggested that when low molecular weight agents act by non-IgE-mediated mechanisms, the asthma can be more severe.

In conclusion, this case shows that zinc can cause OA by a non-IgE-mediated mechanism, and that this diagnosis must not be excluded when specific IgE and contact skin tests are negative. We also stress the possibility that asthma caused by this agent can be particularly severe, and recommend caution when performing the SBPT.

Please cite this article as: Leal A, Caselles I, Rodriguez-Bayarri MJ, Muñoz X. Asma inmunológica no mediada por IgE tras exposición ocupacional a cinc. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:346–347.