Long-term adherence to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea remains suboptimal and low adherence increases healthcare costs. This study investigated relationships between CPAP adherence and the intensity of support provided by homecare providers after implementation of telemonitoring and pay-for-performance reimbursement for CPAP in France.

MethodsAdults who started CPAP in 2018/2019, used telemonitoring, and had ≥1 year of homecare provider data were eligible. The main objective was to determine associations between CPAP adherence at 1 month (low [<2h/night], intermediate [2 to <4h/night], high [≥4h/night]) and the number/type of homecare provider interactions (home visits, phone calls, mask change) during the first year.

ResultsEleven thousand, one hundred sixty-six individuals were included (mean age 59.8±12.7 years, 67% male). The number of homecare provider interactions per person increased significantly as 1-month CPAP usage decreased (7.65±4.3, 6.5±4.0, 5.4±3.4 in low, intermediate and high adherence groups; p<0.01). There was marked improvement in device usage over the first 5–6 months of therapy in the low and intermediate adherence subgroups (p<0.05 after adjustment for age, sex, initial CPAP adherence, and number of interactions). After adjustment for age, sex and 1-month adherence, having 3–4 interactions was significantly associated with better 1-year adherence (odds ratio 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.05–1.46), while having >7 interactions was significantly associated with worse 1-year adherence.

ConclusionsThe telemonitoring/reimbursement scheme in France had a positive impact on CPAP adherence and facilitated a more personalised approach to therapy management, focusing resources on patients with low and intermediate adherence.

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a common condition in which the upper airway collapses intermittently during sleep, resulting in obstructive apnoeas and hypopnoeas that are associated with arousals from sleep and sympathetic activation.1 It has been estimated that more than 900 million adults aged 30–69 years have OSA.2 This number, along with the societal burden of OSA, appears to be increasing.3 In France, an estimated 10 million individuals have OSA,4 and the proportion of these individuals being treated with continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP) has increased over the last decade.5

CPAP is the gold standard therapy for OSA. However, poor adherence to CPAP and high rates of therapy termination for a variety of reasons remain a significant challenge to the clinical effectiveness of this treatment modality.6–9 This is because there is a dose–response effect regarding the effects of CPAP therapy on symptoms and incident comorbidities, and a growing body of evidence showing that there is an association between usage of/adherence to positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and healthcare resource use and costs.8,10–27

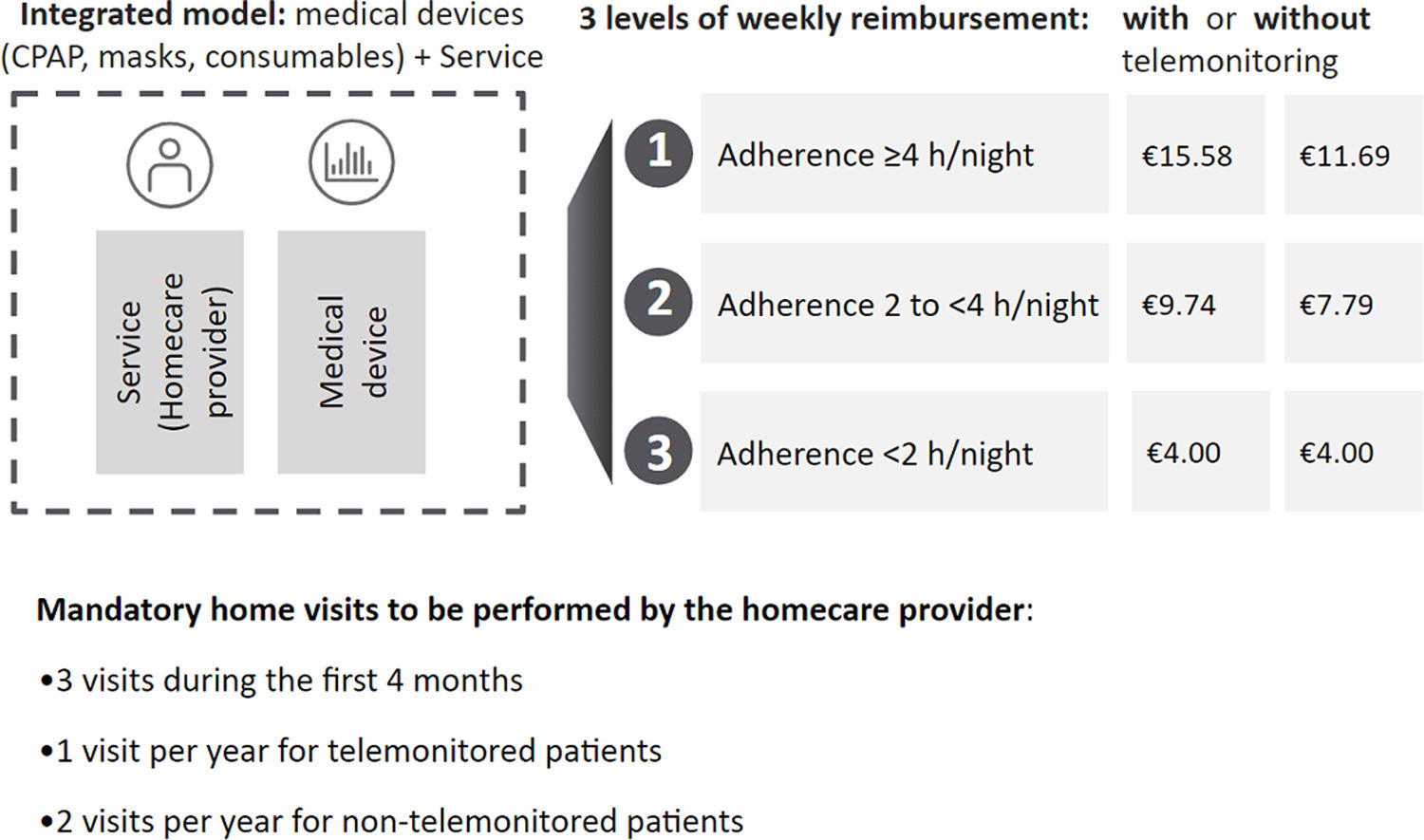

In France, a new national CPAP telemonitoring and pay-for-performance scheme was implemented in 2018 (Fig. 1 and Table S1). This includes incentives to encourage the use of telemonitoring and a higher weekly fee paid to homecare providers if nightly CPAP usage hours increase (calculated based on 28-day moving windows). The system is applied continuously for the duration of CPAP therapy. In 2023, about 97% of CPAP-treated patient in France were being telemonitored. The weekly homecare package fees cover the CPAP device, mask and other consumables, mandatory home visits for device/interface set-up and adjustment, patient education, confirmation of tolerability, adherence monitoring, call centres, and support to improve adherence. Three visits during the first 4 months of CPAP therapy are mandatory, with annual visits thereafter for patients using telemonitoring. Homecare providers also need to provide a call centre service 24h a day, 7 days a week, a telemonitoring platform, and human resources to check telemonitoring data and inform the physician if adherence is poor. Homecare providers can deliver additional visits/calls to improve adherence but this does not result in payment of a higher weekly fee.

Our hypothesis was that the system change that occurred in France in 2018 and the associated introduction of telemonitoring and a pay-for-performance reimbursement model for CPAP-treated patients would have an impact on how homecare providers performed patient follow-up, including additional actions directed to improve adherence in OSA patients who had poor initial CPAP device usage. Therefore, the IMPACT-PAP study investigated relationships between CPAP adherence during the first year of therapy in patients with OSA and the intensity of support provided by homecare providers in France.

Materials and MethodsStudy Design and ParticipantsThis study included adults (age ≥18 years) who were started on CPAP (regular CPAP or automatically titrating CPAP [APAP]) from January 2018 to December 2019, consented to the remote daily telemonitoring of their CPAP data, had at least 1 year of homecare provider data after CPAP therapy initiation, had at least 8 days of CPAP telemonitoring data, and had their CPAP therapy managed by home healthcare provider companies that were affiliated to either of two professional representative unions: Fédération Des Prestataires de Santé à Domicile (FEDEPSAD) or Union des Prestataires de SAnté à Domicile Indépendants (UPSADI). The study was performed in accordance with French regulations, and followed the methodology MR-004 of the French Data Protection Authority (“Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté” CNIL) concerning research that reuses data that have already been collected. Potential participants were provided with written information about the study and were given the opportunity to decline the reuse of their personal data. The study was registered on the national Health Data Hub Website (No. I52121510192019) and did not require IRB approval.

Data CollectionThis study analysed prospectively collected data that were gathered by homecare providers as part of routine practice. This included patient demographical data at the start of CPAP therapy (age, sex and body mass index [BMI; body weight in kg/(height in metres)2]), the date that CPAP therapy was started, objective daily CPAP usage (by date) transmitted from the CPAP device, and the number, date and type of interactions with the homecare provider (phone calls to patients, home visits, change in interfaces).

Participants were divided into subgroups based on the level of therapy adherence (and reimbursement) at 1 month after therapy initiation (low [<2h/night], intermediate [2 to <4h/night], and high [≥4h/night]). The telemonitoring scheme was continued in all patients, irrespective of the level of adherence at 1 month. CPAP could only be discontinued at the request of the patient or by a decision by the treating physician.

ObjectivesThe main objective was to determine the number/type of homecare provider interactions during the first year of treatment based on the level of CPAP adherence at 1 month after therapy initiation. Secondary objectives were to describe the changes trajectories of adherence to CPAP in the first year after therapy initiation, and to determine factors associated with an improvement in the level of therapy adherence during the first year.

Statistical AnalysisData are presented as number and percentage for qualitative variables, and mean±standard deviation for quantitative variables. For the primary endpoint, comparison between the three CPAP adherence groups (low, intermediate and high) were performed using the Chi-squared test for qualitative variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for quantitative variables. Correction for multiple tests were performed using Bonferroni correction. Univariable and multivariable ordinal logistic regressions were performed to determine factors associated with 1-year CPAP adherence (adjusted for age, sex, BMI, type of homecare provider-patient interaction [all, phone calls, visits, mask change], and adherence level group at 1 month after therapy initiation). Changes in CPAP adherence group over time during the first year after therapy initiation were described using a repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA). A linear mixed model with a random effect on patient was used to assess trajectories of CPAP adherence over time, considering interactions between patient and homecare provider and key confounders (patient age and sex, and initial adherence to CPAP therapy). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4. A p-value of ≤0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

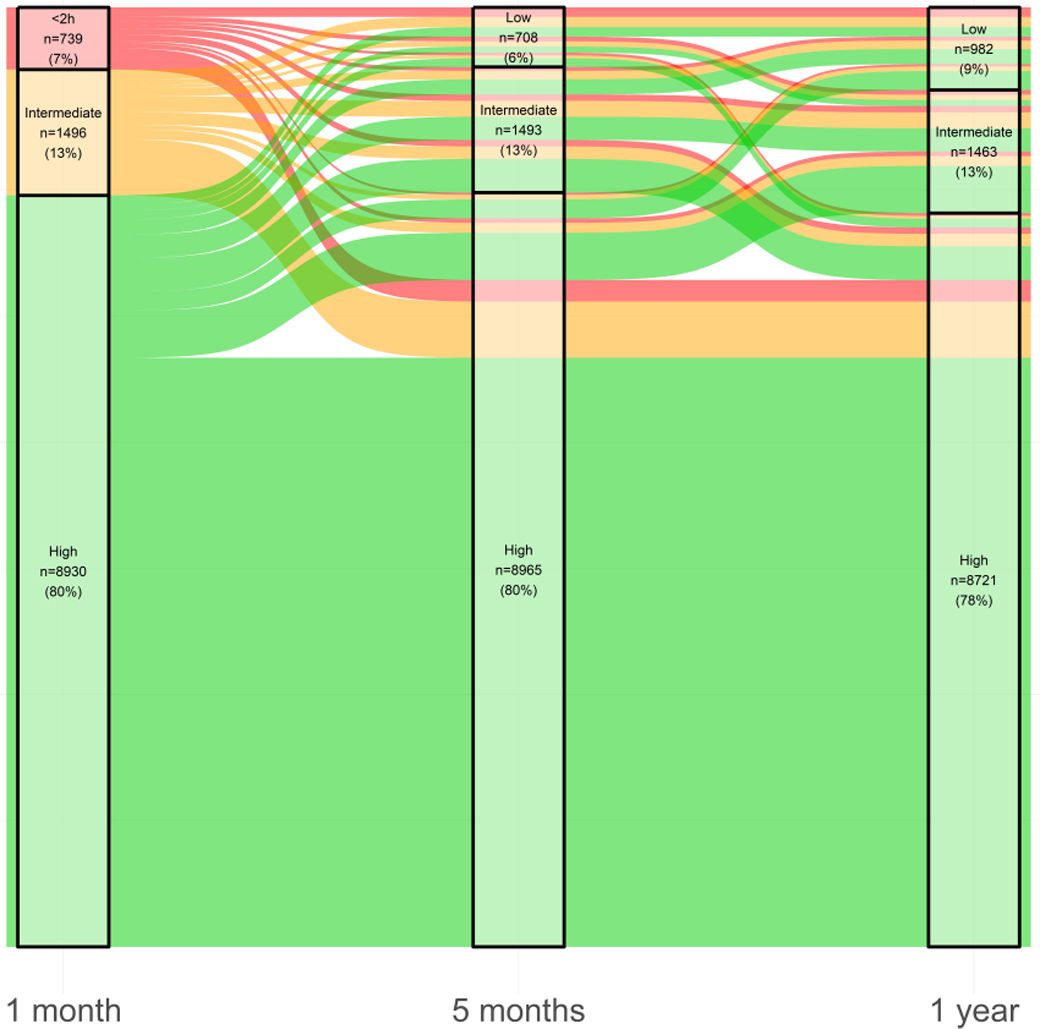

ResultsStudy PopulationA total of 11,166 patients with OSA started on CPAP were included (mean age 59.8±12.7 years, 67% male) (Table 1), representing approximately 6% of the estimated patient population starting CPAP over the study period (see online supplement for details). The majority of patients (78%) had high adherence to CPAP at 1 month after therapy initiation (Table 1). Mean device usage at 1 month was 5.7±2.1h/night overall, 1.0±0.6h/night in low adherers (n=739), 3.1±0.6h/night in intermediate adherers (n=1496), and 6.5±4.0h/night in high adherers (n=8930).

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline, Overall and by Adherence Group at 1 Month After Therapy Initiation.

| Overall(n=11,166) | CPAP Usage Over the First Month | Missing, n | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low(n=739) | Intermediate(n=1496) | High(n=8930) | p-Valuea | |||

| Age, years | 59.8±12.7 | 58.9±13.3 | 57.6±13.2* | 60.2±12.6*,# | <0.01 | 0 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 7442 (66.7) | 505 (68.3) | 1,027 (68.6) | 5,910 (66.2) | 0.11 | 2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32±7.1 | 31.9±7.3 | 31.8±7.2 | 32.0±7.0 | 0.19 | 1194 |

Values are mean±standard deviation, or number of participants (%).

BMI: body mass index; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure monitoring.

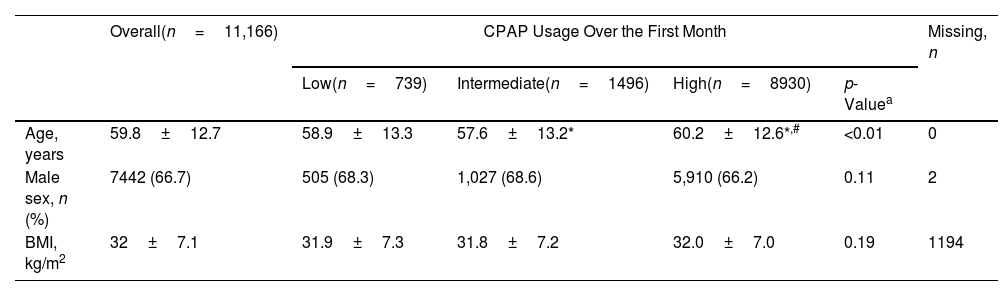

The mean number of home visits per person in the first year was 3.0±1.9, consistent with the relevant regulations (Table 2). The cumulative number of homecare provider interactions (overall, and by type) over the first year of treatment is shown in Fig. S1. The proportion of individuals who received a greater number of home visits in the first year (3–4 and ≥5) was significantly higher in participants with low CPAP usage over the first month of therapy; this was also the case for all other types of homecare provider interactions (i.e. phone calls and mask changes) (Table 2).

Homecare Provider Interactions During the First Year of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy in the Overall Population and in Subgroups Based on Adherence Group at 1 Month After Therapy Initiation.

| Overall(n=11,166) | CPAP Usage Over the First Month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low(n=739) | Intermediate(n=1496) | High(n=8930) | p-Value | ||

| Home visits | 3.0±1.9 | 3.6±2.2 | 3.3±2.0 | 2.9±1.8 | <0.01 |

| Number of patients with, n (%) | |||||

| 1–2 visits per person | 4,496 (40.3) | 214 (29.0) | 537 (35.9)* | 3,744 (41.9)*,a | <0.01 |

| 3–4 visits per person | 5,014 (44.9) | 350 (47.4) | 658 (44)* | 4,006 (44.9)*,a | |

| ≥5 visits per person | 1,656 (14.8) | 175 (23.7) | 301 (20.1)* | 1,180 (13.2)*,a | |

| Phone calls | 1.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.1 | 1.9±1.9 | 1.4±1.6 | <0.01 |

| Number of patients with, n (%) | |||||

| 0 phone calls per person | 4,351 (39.0) | 176 (23.8) | 470 (31.4)* | 3,704 (41.5)*,a | <0.01 |

| 1 phone calls per person | 2,246 (20.1) | 106 (14.3) | 279 (18.6)* | 1,861 (20.8)*,a | |

| 2 phone calls per person | 1,973 (17.7) | 123 (16.6) | 245 (16.4)* | 1,605 (18.0)*,a | |

| 3 phone calls per person | 1,123 (10.1) | 109 (14.7) | 190 (12.7)* | 824 (9.2)*,a | |

| >3 phone calls per person | 1,473 (13.2) | 225 (30.4) | 312 (20.9)* | 936 (10.5)*,a | |

| Mask changes | 1.1±1.2 | 1.3±1.2 | 1.1±1.2 | 1.1±1.1 | <0.01 |

| Number of patients with, n (%) | |||||

| 0 mask changes per person | 4,329 (38.8) | 245 (33.2) | 574 (38.4)* | 3,509 (39.3)* | <0.01 |

| 1 mask change per person | 3,573 (32.0) | 203 (27.5) | 455 (30.4)* | 2,915 (32.6)* | |

| ≥2 mask changes per person | 3,264 (29.2) | 291 (39.4) | 467 (31.2)* | 2,506 (28.1)* | |

| Total interactions | 5.7±3.6 | 7.65±4.3 | 6.5±4.0 | 5.4±3.4 | <0.01 |

| Number of patients with, n (%) | |||||

| 0–2 interactions per person | 1,570 (14.1) | 64 (8.7) | 179 (12.0)* | 1,326 (14.8)*,a | <0.01 |

| 3–4 interactions per person | 4,436 (39.7) | 86 (11.6) | 296 (19.8)* | 2,488 (27.9)*,a | |

| 5–7 interactions per person | 3,290 (29.5) | 254 (34.4) | 509 (34.0)* | 3,288 (36.8)*,a | |

| >7 interactions per person | 905 (8.1) | 335 (45.3) | 512 (34.2)* | 1,828 (20.5)*,a | |

Values are mean±standard deviation, or number of patients (%).

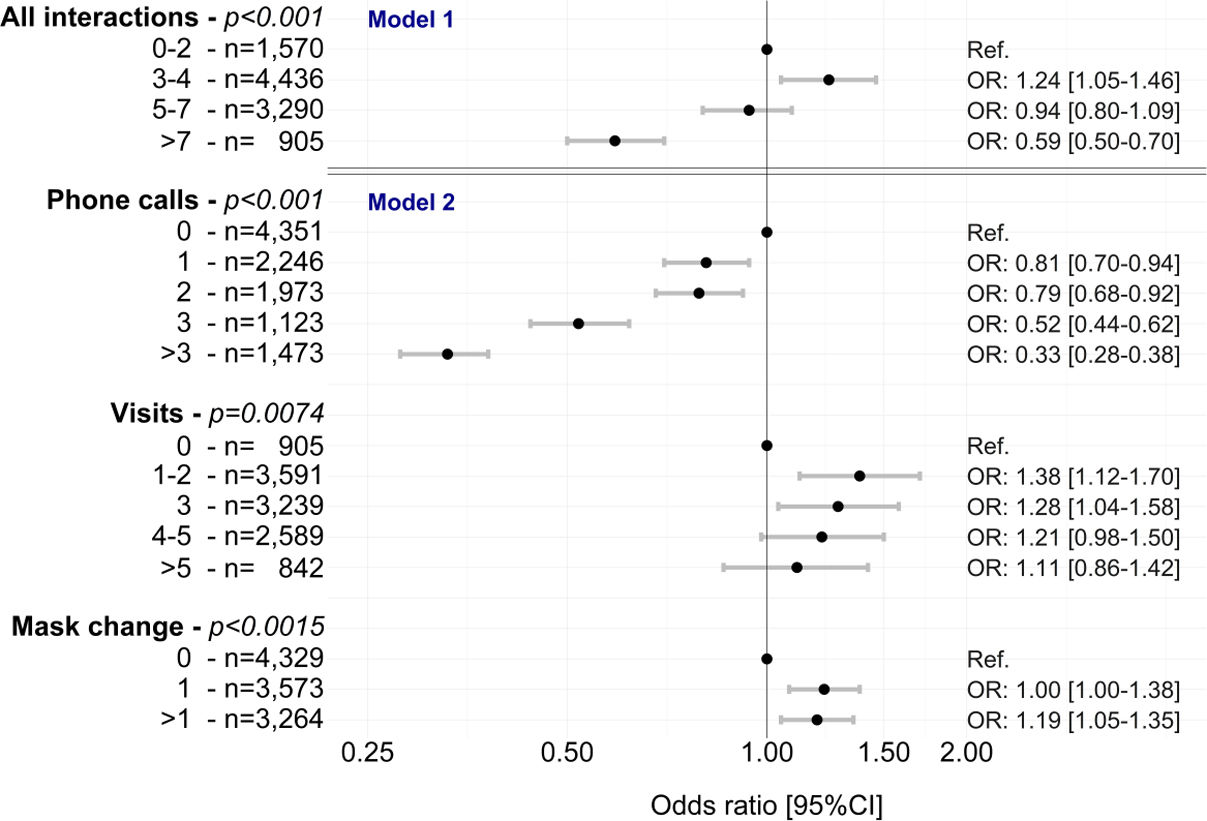

After adjustment for age, sex and adherence at 1 month, having 3–4 total interactions was significantly associated with better 1-year adherence (odds ratio [OR] 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.46) (Fig. 2 and Table S2). Having >7 total interactions was significantly associated with worse 1-year adherence (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.50–0.70) (Fig. 2 and Table S2). Of the different types of interactions, home visits (up to 3) and mask changes (at least one) were significantly associated with better 1-year adherence (Fig. 2 and Table S2). Having any number of phone calls was significantly associated with worse 1-year adherence (Fig. 2 and Table S2).

Multivariable analyses (mixed ordinal regressions) of the association between homecare interactions (overall [model 1] and by type [model 2]) and changes in adherence to continuous positive airway pressure in the first year of therapy. All models were adjusted for age, sex and time, including a random effect on patient. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

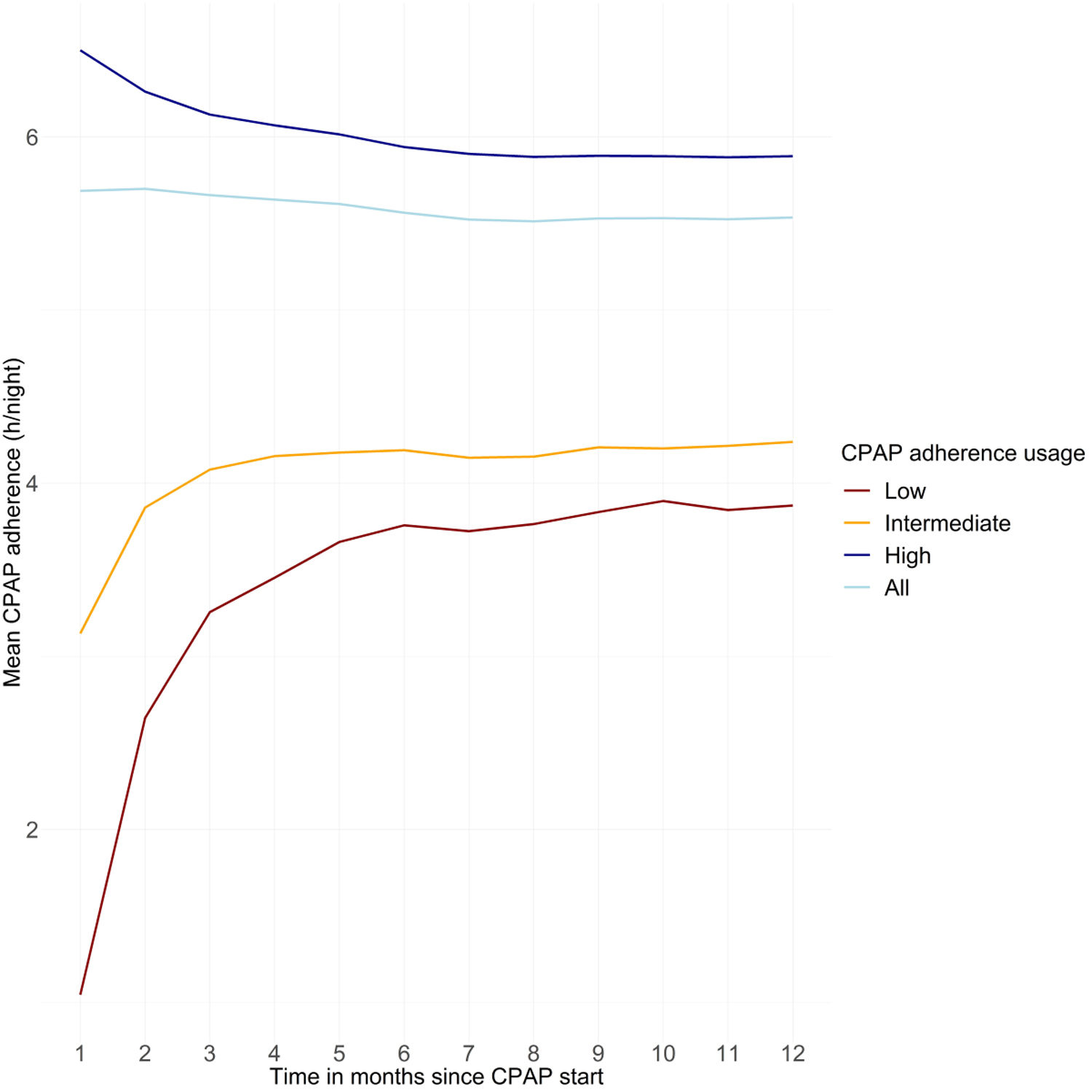

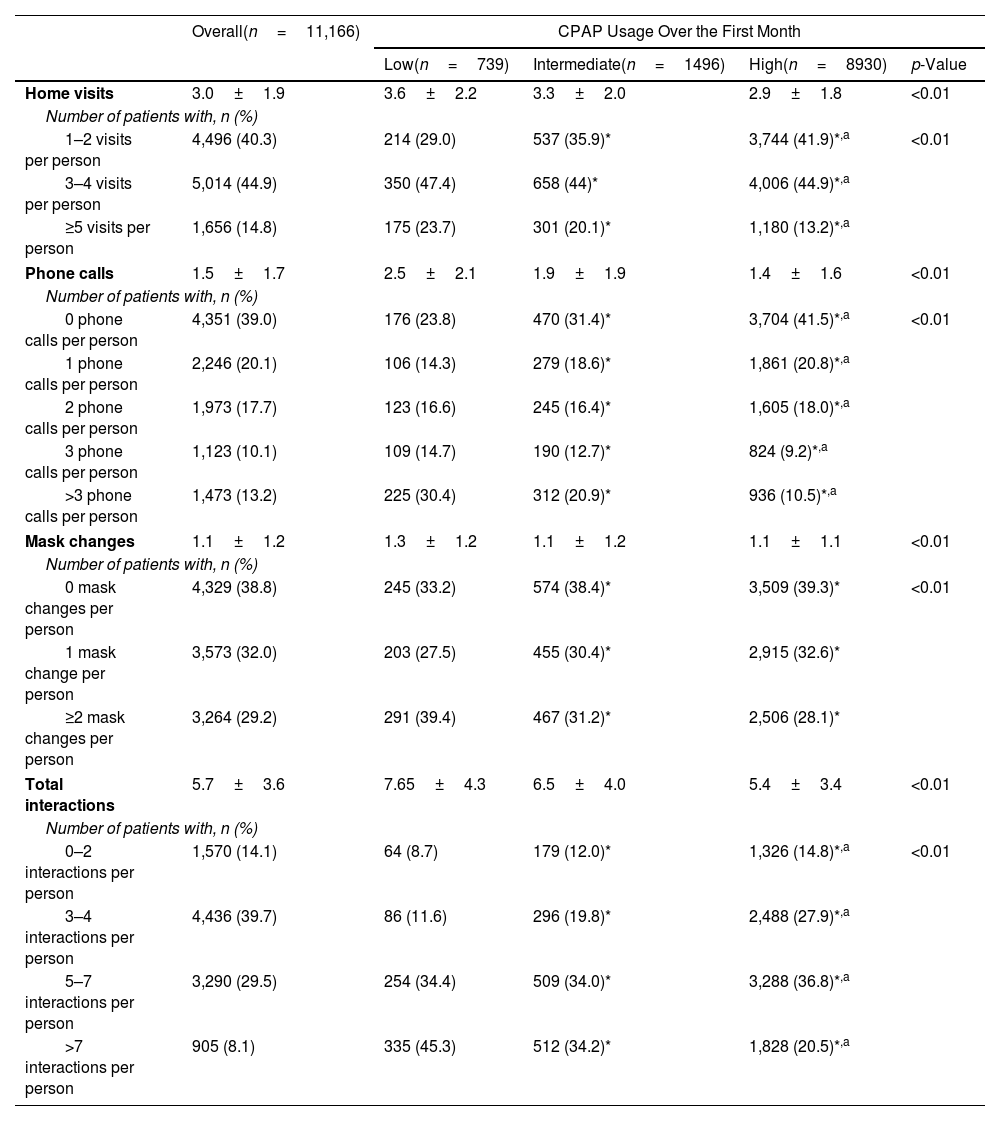

Mean device usage at 1 year was 5.5±2.2h/night overall, 3.9±2.4h/night in those with low adherence at 1 month, 4.2±2.2h/night in those with intermediate adherence at 1 month, and 5.9±2.0h/night in those with high adherence at 1 month. There was initial marked improvement in device usage over the first 6 months of therapy in the subgroups with low or intermediate adherence at 1 month after therapy initiation (Fig. 3). The increase in CPAP adherence over the first 6 months of therapy was statistically significant in a multivariable mixed model considering time in months and adjusted for age, sex, initial CPAP adherence, and number of homecare provider-patient interactions (p<0.05); changes in CPAP adherence from 6 to 12 months were not statistically significant.

Changes in adherence group (low, intermediate or high device usage) mainly occurred during the first 5 months of therapy (Fig. 4). Eighty-four percent of patients who had high adherence to CPAP therapy at 1 month maintained that level of usage at 1 year, 56.9% who had intermediate adherence at 1 month had high adherence at 1 year, and 49.5% who had low adherence at 1 month had high adherence at 1 year.

Sankey plot showing the trajectories of continuous positive airway pressure device usage over the first year of therapy. At each timepoint, the number (%) of patients in each compliance class (<2h/n; 2–4h/n; ≥4h/n) is indicated. The colours of the lines represent the 1-month adherence subgroup (low [<2h/night] in red; intermediate [2 to <4h/night] in orange; high [≥4h/night] in green), and increasing line thickness indicates an increasing number of patients.

Patients who improved their CPAP device usage during the first year of therapy were significantly younger and had significantly more interactions with the homecare provider (overall and by type) compared with individuals who had consistently high adherence (Table S3). The number of homecare provider interactions varied based on the change in CPAP adherence group over time. For example, in the subgroup with low adherence at 1 month, the mean number of phone calls per person was higher in those who still had low adherence at 1 year (2.98) than in those who had improved to having high adherence at 1 year (2.27), and was highest in the group with intermediate adherence at 1 month and low adherence at 12 months (3.32) (Fig. S2).

DiscussionIn this cohort of CPAP-treated patients with OSA from France, the widespread national implementation of a telemonitoring and a pay-for-performance scheme for homecare providers had an important impact on the number of interactions targeting patient adherence during the first year after CPAP initiation. Patients with low or intermediate CPAP usage (<4h/night) in the first month after therapy initiation received a higher volume and different type of support than adherent patients. Homecare provider interactions for patients with low early adherence occurred primarily during the first five months after therapy initiation. In addition, there was a ceiling effect in terms of the number of interactions, whereby an increase above four interactions per patient was not associated with any further improvement in adherence, suggesting that interactions after that point become unhelpful, and potentially a waste of resources.

The increasing number of patients diagnosed with OSA and managed with CPAP therapy places a significant burden on finite healthcare resources. Therefore, new approaches to the management of CPAP therapy that strike a balance between remote monitoring utilising digital technologies and in-person patient-healthcare professional contacts are needed, as suggested by a study conducted in Finland.3 However, to date, little attention has been paid to the assessment of new management pathways, including pay-for-performance models, in terms of their effect on patient care and adherence to CPAP therapy. Our study is novel in highlighting the impact of the national deployment of a novel strategy for the management of CPAP therapy, and in showing that financial performance incentives encourage homecare providers to target resources and interactions to individuals who have the lowest CPAP adherence in the first month of therapy.

Our finding that >4 interactions per person were not associated with any incremental CPAP device usage benefit suggests that the reasons underlying persistent poor adherence are probably not related to technical aspects that can be addressed by homecare provider interactions. Instead persistent poor adherence might be explained by other factors such as health behaviours, attitudes and beliefs, the presence of insomnia or other comorbidities that result in disturbed sleep, and/or socioeconomic factors.6,28 The identification of these factors is essential to allow the application of different strategies to target these specific issues with the goal of improving CPAP device usage and therapy benefit.

This study also determined the relative impact of different types of homecare interactions (phone call, home visit, mask change). Mask resupply has already been shown to be associated with improved long-term adherence to CPAP therapy.29,30 In this analysis, our data suggested that face-to-face visits were more effective than phone calls at improving CPAP device usage. In contrast, it has previously been shown that telemonitoring with automated feedback messaging was sufficient to improve 90-day adherence to CPAP therapy in an unselected population.31

Consistent with existing evidence,32–34 our data showed that when CPAP adherence is achieved early, it is generally maintained over time (between 1 month and 1 year based on our data). Homecare provider interactions are generally concentrated in the first 5 months after CPAP therapy initiation and reduce thereafter. Our findings support this approach, because more than four interactions within the first year of therapy was not associated with any incremental benefit on CPAP device usage at 1 year.

Overall, our study clearly shows that regular reassessment of device usage (adherence) by telemonitoring combined with a pay-for-performance strategy means that homecare provider actions are targeted to individuals with lower CPAP adherence, which was associated with overall improved adherence and a greater number of patients achieving adherence of >4h/night. Telemonitoring is a key component of this approach, and enables or triggers the appropriate educational or supportive actions by the homecare provider.35,36 Another important message from our analysis is that the current French model, which includes three compulsory visits in the first 4 months after CPAP therapy initiation, does not consider the diversity of patients and OSA phenotypes. Therefore, the current system could potentially be revised to allow avoidance of home visits for individuals with good early adherence that is stable over time. This may contribute to more efficient allocation of healthcare resources. A better approach might be to allow homecare providers to operate using a patient-centred model, with varying levels and types of support based on each individual's profile, within the current pay-for-performance-based strategy.

Strengths of this study include the representativeness of the study population, which covers approximately 6% of the total number of incident individuals starting CPAP in France in 2018–2019. In addition, the data were obtained from a range of different providers, non-profit organisations and private companies, who may have had different processes for patient management. There are also some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting our results. Firstly, we did not have any data on sleep duration, OSA severity (symptoms, AHI at diagnosis), comorbidities or socioeconomic factors to allow us to adjust for the impact of these potential confounders on adherence.13,37 Secondly, although we had information about the number and type of homecare provider interactions, we did not have details about the specific reason for each interaction. Finally, this study included patients who had a full year of follow-up data after CPAP therapy initiation and are therefore only applicable to similar individuals who have persisted with CPAP therapy and accept interactions with their homecare provider. The findings also relate to the current CPAP management policies and protocols in France and therefore may not be directly applicable to different healthcare settings and practices.

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time that a CPAP telemonitoring and pay-for-performance scheme for homecare providers can have a positive impact on adherence to CPAP therapy and redirects interactions to those with low early adherence. This facilitates a more personalised approach to CPAP therapy management, and has the potential to contribute to improved outcomes.

Role of SponsorRepresentatives of the study sponsor were involved in the design of the study. Data from the different homecare companies involved in the study were collated by an independent clinical research organisation (Alira Health), which also performed data cleaning and homogenisation. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by JLP, SB and JT with the assistance of an independent medical writer funded by FEDEPSAD. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by all the authors. All authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the analyses and for the fidelity of this report to the trial protocol.

FundingThis study was funded by two French professional representative unions (FEDEPSAD, Fédération Des Prestataires de Santé à Domicile and UPSADI, Union des Prestataires de SAnté à Domicile Indépendants) and ResMed. JLP and SB are supported by the French National Research Agency in the framework of the “Investissements d’avenir” program (ANR-15-IDEX-02) and the “e-health and integrated care and trajectories medicine and MIAI artificial intelligence” chairs of excellence from the Grenoble Alpes University Foundation. This work was partially supported by MIAI @ Grenoble Alpes (ANR-19-P3IA-0003).

Authors’ ContributionsJLP, SB and JT prepared the outline for the first draft manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by JLP, SB and JT with the assistance of an independent medical writer (Nicola Ryan) funded by FEDEPSAD. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by all the authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of InterestJT is an employee of Air Liquide Healthcare. J-CB is an employee of AGIR à Dom. AS is an employee of SOS Oxygène. JLP has received lecture fees or conference traveling grants from ResMed, Perimetre, Philips, Fisher and Paykel, AstraZeneca, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Agiradom and Teva, and has received unrestricted research funding from ResMed, Philips, GlaxoSmithKline, Bioprojet, Fondation de la Recherche Medicale (Foundation for Medical Research), Direction de la Recherche Clinique du CHU de Grenoble (Research Branch Clinic CHU de Grenoble), and fond de dotation “Agir pour les Maladies Chroniques” (endowment fund “Acting for Chronic Diseases”). SB has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Nicola Ryan, independent medical writer, funded by FEDEPSAD.

![Multivariable analyses (mixed ordinal regressions) of the association between homecare interactions (overall [model 1] and by type [model 2]) and changes in adherence to continuous positive airway pressure in the first year of therapy. All models were adjusted for age, sex and time, including a random effect on patient. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. Multivariable analyses (mixed ordinal regressions) of the association between homecare interactions (overall [model 1] and by type [model 2]) and changes in adherence to continuous positive airway pressure in the first year of therapy. All models were adjusted for age, sex and time, including a random effect on patient. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03002896/0000006000000012/v2_202412091118/S030028962400228X/v2_202412091118/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w98FxLWLw1xoW2PaQDYY7RZU=)

![Sankey plot showing the trajectories of continuous positive airway pressure device usage over the first year of therapy. At each timepoint, the number (%) of patients in each compliance class (<2h/n; 2–4h/n; ≥4h/n) is indicated. The colours of the lines represent the 1-month adherence subgroup (low [<2h/night] in red; intermediate [2 to <4h/night] in orange; high [≥4h/night] in green), and increasing line thickness indicates an increasing number of patients. Sankey plot showing the trajectories of continuous positive airway pressure device usage over the first year of therapy. At each timepoint, the number (%) of patients in each compliance class (<2h/n; 2–4h/n; ≥4h/n) is indicated. The colours of the lines represent the 1-month adherence subgroup (low [<2h/night] in red; intermediate [2 to <4h/night] in orange; high [≥4h/night] in green), and increasing line thickness indicates an increasing number of patients.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03002896/0000006000000012/v2_202412091118/S030028962400228X/v2_202412091118/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w98FxLWLw1xoW2PaQDYY7RZU=)