Given the difficulties in diagnosing and treating patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) in general, and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB) in particular, the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) published guidelines in 2017 to facilitate the management of these entities1. These SEPAR guidelines were updated in 20202 to include the accumulated evidence on new drugs and their rational and sequential use3–5, and to adapt the recommendations to those published by the WHO in 20196,7 and 20208,9. The WHO has now published new definitions of RR-TB10, prompting us to revisit the SEPAR guidelines.

RR-TB, which is also resistant to isoniazid (H), was given a specific name: multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB)6,9,11. Both RR-TB and MDR-TB were subsequently found to have a similar prognosis, due to resistance to R, the most important drug in the treatment of TB12. This is now called MDR/RR-TB, and prevalence in 2019 was 465,000 cases worldwide11. This definition of MDR/RR-TB remains unchanged in the new WHO publication10.

Five to10 years ago, only 2 groups of drugs had demonstrated good efficacy in the treatment of patients with MDR/RR-TB – fluoroquinolones (FQ) and second-line injectable drugs (SLID), which included 3 drugs: amikacin, kanamycin, and capreomycin13. Since the prognosis of MDR/RR-TB patients depended fundamentally on the efficacy of these 2 drug groups, in 2006 the WHO coined a new term: extensively resistant TB (XDR-TB), which encompassed cases of MDR-TB that were also resistant to any FQ and at least 1 SLID12,13. However, clinicians often used another term that was never officially accepted: pre-XDR-TB, which were MDR/RR-TB cases that were also resistant to FQ or SLID, but not both. Thus, there was pre-XDR-TB that was resistant to FQ but sensitive to SLID; and pre-XDR-TB that was resistant to SLID but sensitive to FQ. Over time, the prognosis of pre-XDR-TB with FQ resistance was seen to be clearly worse than that of pre-XDR-TB with SLID resistance12,14.

Fortunately, the prognosis of resistant TB has improved remarkably in the last 5 years, thanks in particular to the introduction of new drugs with good anti-M. tuberculosis activity (bedaquiline [Bdq], delamanid, pretomanid), and the discovery that other antibiotics used for other infections (FQ, linezolid [Lzd], clofazimine [Cfz]) are also very effective in TB3,13. This evidence prompted the WHO to perform a meta-analysis in 20183 to study the potential role of each drug with anti-M. tuberculosis activity in the treatment of MDR/RR-TB. The main conclusions of the study were: 1) the best drugs were FQ, Lzd, and Bdq, and these therefore were included in group A of the new classification of rational drug use in the 2019 WHO guidelines6 and in group 2 of the 2020 SEPAR guidelines2; and 2) the efficacy of the SLIDs was clearly lower than previously thought3, and their toxicity means that they must be reserved for special situations in which no other medicines are available and when adverse effects can be closely monitored3,9,12.

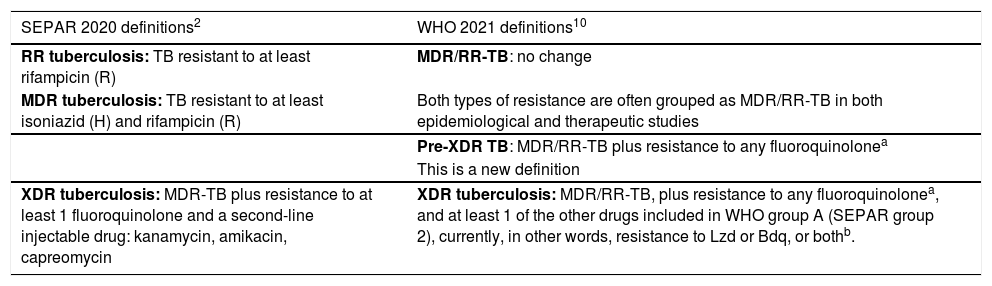

Following the removal of SLIDs from the state-of-the-art arsenal and the arrival of new active drugs for the treatment of MDR/RR-TB, the WHO organized a meeting in late 2020 to redefine the concepts of drug-resistant TB10. They did not alter the definitions of TB-RR/MDR, but they did modify the definition of XDR-TB, and have now officially included the definition of pre-XDR-TB. It is accepted that pre-XDR-TB is MDR/RR-TB that is also resistant to FQ, and all mention of SLIDs has been eliminated. This changes the concept of XDR-TB in cases who present pre-XDR-TB plus resistance to at least 1 of the other drugs included in WHO group A (SEPAR group 2), i.e, currently, resistance to Lzd or Bdq, or both10. The definition refers to group A drugs, and will also apply to any other drugs included in this group in the future.

Although these new WHO definitions10 (summarized in Table 1) are both correct and important, they have very little impact on the clinical strategies recommended in the updated SEPAR guidelines published in 20202. This is because the vast majority of the recommendations addressed the diagnosis and treatment of MDR/RR-TB, the most common form, and these remain unchanged. Even the small section which, at that time, was devoted to the “Treatment of patients with XDR-TB or even broader resistance patterns” remained unchanged, and the advice that “XDR-TB must be treated by highly specialized clinicians and in units that can guarantee close supervision of the treatment and the proper management of adverse reactions” remains in force.

| SEPAR 2020 definitions2 | WHO 2021 definitions10 |

|---|---|

| RR tuberculosis: TB resistant to at least rifampicin (R) | MDR/RR-TB: no change |

| MDR tuberculosis: TB resistant to at least isoniazid (H) and rifampicin (R) | Both types of resistance are often grouped as MDR/RR-TB in both epidemiological and therapeutic studies |

| Pre-XDR TB: MDR/RR-TB plus resistance to any fluoroquinolonea | |

| This is a new definition | |

| XDR tuberculosis: MDR-TB plus resistance to at least 1 fluoroquinolone and a second-line injectable drug: kanamycin, amikacin, capreomycin | XDR tuberculosis: MDR/RR-TB, plus resistance to any fluoroquinolonea, and at least 1 of the other drugs included in WHO group A (SEPAR group 2), currently, in other words, resistance to Lzd or Bdq, or bothb. |

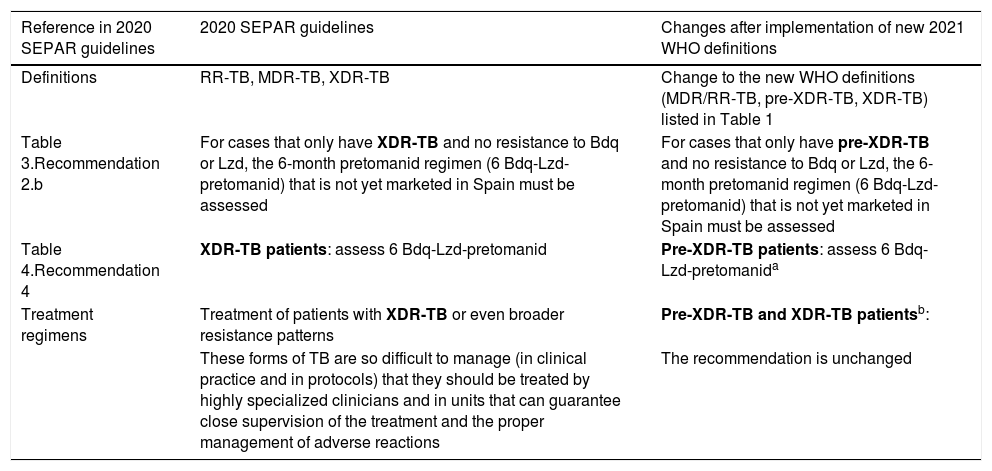

These new WHO definitions10, then, would only require the following changes in the 2020 SEPAR guidelines2 (detailed in Table 2):

- 1

Inclusion of the new pre-XDR and XDR-TB definitions.

- 2

Inclusion of the pretomanid regimen (6 Bdq-Lzd-pretomanid) indication in the current pre-XDR-TB, but not in the new XDR-TB definition.

| Reference in 2020 SEPAR guidelines | 2020 SEPAR guidelines | Changes after implementation of new 2021 WHO definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Definitions | RR-TB, MDR-TB, XDR-TB | Change to the new WHO definitions (MDR/RR-TB, pre-XDR-TB, XDR-TB) listed in Table 1 |

| Table 3.Recommendation 2.b | For cases that only have XDR-TB and no resistance to Bdq or Lzd, the 6-month pretomanid regimen (6 Bdq-Lzd-pretomanid) that is not yet marketed in Spain must be assessed | For cases that only have pre-XDR-TB and no resistance to Bdq or Lzd, the 6-month pretomanid regimen (6 Bdq-Lzd-pretomanid) that is not yet marketed in Spain must be assessed |

| Table 4.Recommendation 4 | XDR-TB patients: assess 6 Bdq-Lzd-pretomanid | Pre-XDR-TB patients: assess 6 Bdq-Lzd-pretomanida |

| Treatment regimens | Treatment of patients with XDR-TB or even broader resistance patterns | Pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB patientsb: |

| These forms of TB are so difficult to manage (in clinical practice and in protocols) that they should be treated by highly specialized clinicians and in units that can guarantee close supervision of the treatment and the proper management of adverse reactions | The recommendation is unchanged |

The WHO has also just released a rapid communication updating the use of molecular tests to detect TB and DR-TB15, most of which were already recommended in the SEPAR 2020 guidelines2. The most important innovation is the inclusion of Xpert MTB/XDR (Cepheid), a low-complexity technique similar to Xpert MTB that in less than 2 hours detects mutations linked to resistance to H, FQ (perhaps the great advantage of this technique), amikacin, and etionamide, and is indicated in patients in whom RR-TB has been detected by any method. Another novelty is the Genoscholar PZA-TB II, which can be used to detect pyrazinamide resistance, although this technique is more complex. It would also be advisable to implement techniques to diagnose resistance to Bdq and Lzd, given the importance of these drugs in the therapeutic arsenal and new definitions of resistant TB.

In conclusion, the update of the 2020 SEPAR guidelines2 changes little, although we must take into account the revised WHO definitions of DR-TB in respect of the new meaning of pre-XDR-TB and the change in the definition of XDR-TB. Furthermore, rapid detection of FQ resistance, and thus of pre-XDR-TB, is also an important development.

Finally, we would like to underline the importance of the new drugs, especially bedaquiline, and support institutional efforts to make them available across Spain. The Plan for TB Prevention and Control will no doubt be of assistance in this initiative and will help implement the new guidelines16.

FundingThis study has not received specific grants from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit organizations. No funding was received.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests directly or indirectly related with the contents of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Caminero JA, García-García J-M, Caylà JA, García-Pérez FJ, Palacios JJ, Ruiz-Manzano J. Tuberculosis con resistencia a fármacos: nuevas definiciones de la OMS y su implicación en la Normativa de SEPAR. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:87–9.