The main reasons for rejecting papers submitted to Archivos de Bronconeumologia and other journals with an impact factor are methodological shortcomings in the scientific design and lack of originality in the research question.

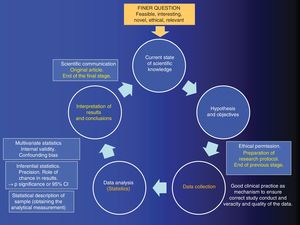

Clinicians, for different reasons, tend to lose sight of the scientific method cycle (SMC),1 and attempt to jump in directly at the stage of statistical exploitation of a clinical database, without passing through the previous steps of formulating the research question and objectives and selecting the correct methodology to achieve the proposed objectives. At the same time, too much faith is often placed in the famouspof significance, without taking into account that inferential statistics occupy only a small part of the overall SMC.

In this editorial, inspired by the workshop entitled “We have to publish in a journal with an impact factor”, held during the 6thACINAR Conference organized by the Cantabrian Association for Respiratory System Research, we will try to explain why we should never put the cart before the horse, and remind authors that research is a systematic, sequential, and orderly process aimed at answering a research question. We have summarized the SMC is diagram form in Fig. 1.

The process of analytical quantitative research must first begin with the so-called “FINER” research question, i.e., it should be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant.1 Let us pause at “N” for novel, since this the key that opens the door to the SMC. If the question is completely novel, the research results will be original, and the cycle will culminate in an original article — the epitome of research excellence

This research question, once it is part of the SMC, is transformed into a written, working hypothesis.2 Once the hypothesis has been formulated, the objectives are laid out, i.e., the explicit statement of what is to be achieved with the study. Once the study objectives have been formulated, the methodology used to achieve the proposed objectives is developed. This includes both the study design and other epidemiological and statistical factors. If a study is poorly designed, it is unlikely to have sufficient statistical power, or it will lack internal validity.

In the field of public health, a cohort design necessarily involves individuals that are disease-free (epidemiologically healthy) at the beginning of the study, but are at risk of developing disease (lung cancer, for example), and undergo a period of prospective follow-up. A clinical trial is a study in which patients are susceptible to cure or improvement from the outset, and are prospectively followed up. As it is experimental, randomizing the intervention and blinding participants minimizes the possibility of bias in favor of the internal validity of the results.

When it comes to studying COPD patients seen consecutively in pulmonology departments to estimate the percentage of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in this population, by the end of the recruitment stage the study will include both patients with and without the event i.e., with and without the deficiency. Therefore, the design will be cross-sectional, and its frequency measurement will be prevalence.

A case-control design differs from a cross-sectional design: cases are first recruited (new cases of lung cancer identified each week in the participating hospitals), then individuals without cancer (controls) are interviewed, and the data on the exposure under study are collected retrospectively.

Once the database with quality information is generated, descriptive statistics are used to calculate the “analytical measure”. Examples of this type of measurement include the odds ratio or relative risk, and the hazard ratio or the difference in means.

Inferential statistics will then be used to rule out the role of chance in our results, and chance or random error is quantified using the corresponding standard error formula. Once this is quantified, it will be weighed up against the analytical measure, resulting in a p of significance that, by convention, is statistically significant if it is less than 0.05 (which is synonymous with rejecting the famous statistical null hypothesis with an alpha error of 5%). Another option is to use the standard error to build confidence intervals, which also allow us reject the null hypothesis. The breadth or narrowness of confidence intervals give the so-called “effect size”, and, therefore, the precision of the study.3 Thus, it should be clear that precision is the lack of randomized error, and that if a result is statistically significant, it does not mean it is true.4,5

Internal validity is a parallel world to precision, as it measures the lack of bias or systematic errors. If the study is biased, the result may be statistically significant, but not necessarily true. Multivariate statistics can be used in this respect to control a type of bias that is the confounding bias, if this could not be controlled in the design phase.6

Assuming that a study has internal validity, the fact that a result is statistically significant will only tell us that the chance of this occurring cannot be fully explained. It is important to bear in mind that this does not imply that the result is clinically relevant.7

Finally, we must not forget external validity, which refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be generalized and applied to our patients.8,9 The greater the number of exclusion criteria in the selection of the study population, the lower the external validity.

Please cite this article as: Santibáñez M, García-Rivero JL, Barreiro E. No se debe empezar la casa por el tejado (si queremos publicar en una revista de impacto). Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:70–71.