There is currently a growing interest in the identification of different phenotypes among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We are under the impression that there are subgroups of patients with quite different characteristics, which should have prognostic and therapeutic implications. We now consider COPD to be a multidimensional disease with an important extrapulmonary affectation, where forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) is clearly insufficient to adequately express phenotypic heterogeneity.1 García-Aymerich et al.2 have demonstrated how different target organs intervene in COPD as well as a complexity of cellular, organic, functional, and clinical events, identifying 6 dimensions and some 26 phenotypic features. Respiratory symptoms, state of health, exacerbations, functional anomalies, structural alterations, local and systemic inflammation, and other systemic effects are the dimensions where these phenotypic features gather.

From a clinical standpoint, 2 COPD phenotypes have classically been described: the “blue bloaters”, who are overweight and cyanotic, and the “pink puffers”, who are asthenic, even cachectic, with prolonged expiration, semi-closed lips, and normal coloring. It is true, however, that these patients represent the extremes of this disease and it is nowadays uncommon to come across these extreme phenotypes.3 The Spanish COPD Guidelines, which will soon be published, will be the first to define 3 COPD phenotypes with clinical implications: emphysematous, frequent exacerbator, and mixed COPD asthma.4

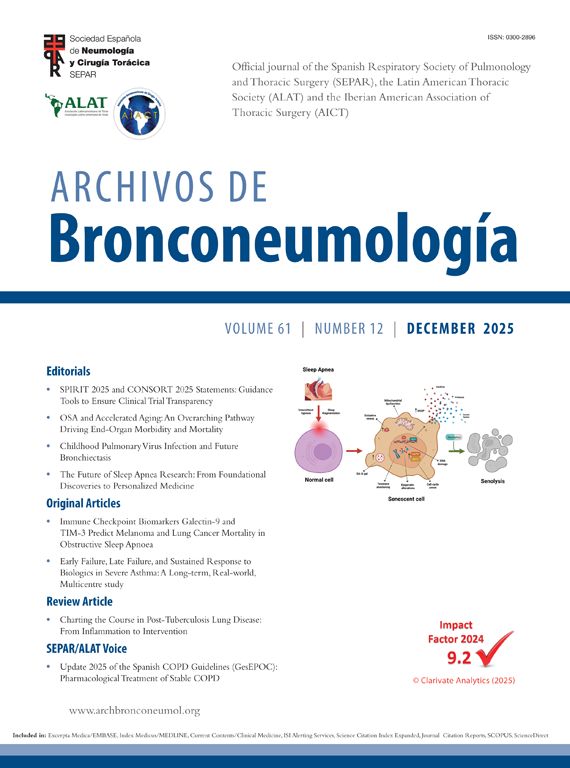

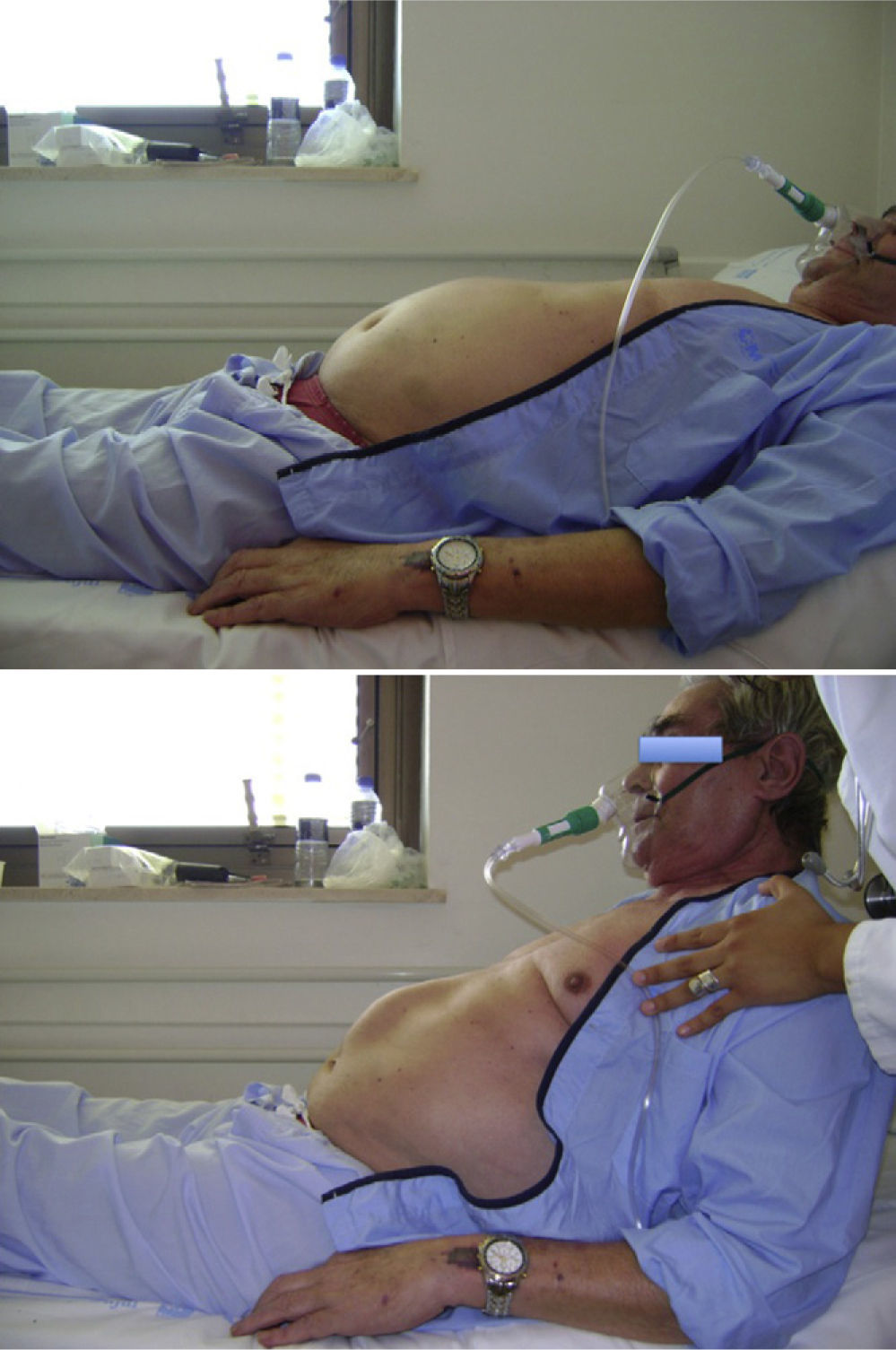

For years, Dr. Sueiro has been calling attention to the existence of a COPD morphotype that is very frequent in the hospital ward and in outpatient consultations. These patients have a certain degree of trunk obesity, short neck, increased ribcage diameter at the lower portion, and diastasis of the anterior straight muscles (Fig. 1). They usually present overall respiratory failure, with slightly high levels of PaCO2 (50–55mmHg), and pulse-oximetry shows levels of arterial saturation below 90%, but these recover when the patient does hyperventilation and Valsalva maneuvers (halting expiration, coughing or simulated laughter), even reaching levels of 95%. Spirometry shows moderate bronchial obstruction (FEV1 levels compatible with GOLD stages II–III). These patients usually receive home oxygen therapy and, on occasion, also night-time mechanical ventilation with double pressure levels. If this type of patient lies down in bed and is then asked to sit up, he/she presents a herniation of the abdominal content at the diastasis of the straight muscles of the upper abdomen (Fig. 2), which we call “Sueiro's sign”. More advanced cases present umbilical hernia, forming what we call “Sueiro's triad”: diastasis recti, upper abdominal herniation when rising and umbilical hernia.

These findings explain the inefficient ventilatory mechanics, as part of the intrathoracic pressure is lost due to the diastasis of the straight muscles. In those patients who undergo a sleep study, nocturnal desaturation is observed and, occasionally, also mixed apnea. This COPD patient morphotype should be individualized and identified as a prototype “overlap” patient in whom bronchial obstruction is associated with diaphragmatic inefficiency and a component of obesity, which favors the appearance of hypoventilation. Recognizing this patient phenotype, in addition to being a tribute to Dr. Sueiro, would justify specific studies to better understand its physiopathological and prognostic implications as well as the most appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Please cite this article as: Díaz Lobato S. Fenotipos de la EPOC: el signo de Sueiro. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;48:33–4.