There are multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments against nicotine dependence. However, there are few guidelines to answer frequent questions asked by a clinician treating a smoker. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to facilitate the treatment of tobacco addiction.

Material and methods12 PICO questions are formulated from a GLOBAL PICO question: “Efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatment of tobacco dependence”. A systematic review was carried out to answer each of the questions and recommendations were made. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system was used to grade the certainty of the estimated effects and the strength of the recommendations.

ResultsVarenicline, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion and cytisine are more effective than placebo. Varenicline and combined nicotine therapy are superior to the other therapies. In smokers with high dependence, a combination of drugs is recommended, being more effective those associations containing varenicline. Other optimization strategies with lower efficacy consist of increasing the doses, the duration, or retreat with varenicline. In specific populations varenicline or NRT is recommended. In hospitalized, the treatment of choice is NRT. In pregnancy it is indicated to prioritize behavioral treatment. The financing of smoking cessation treatments increases the number of smokers who quit smoking. There is no scientific evidence of the efficacy of pharmacological treatment of smoking cessation in adolescents.

ConclusionsThe answers to the 12 questions allow us to extract recommendations and algorithms for the pharmacological treatment of tobacco dependence.

Smoking is an addictive and chronic disease with a high population impact and, as such, requires treatment based on drugs against nicotine dependence and psychological counseling, thus tripling the chances of smoking cessation.1,2 A recently published study shows that the implementation of both treatments would lead to a reduction in mortality by the year 2050 of 180 million people. In other words, the availability of effective and safe treatments for smoking cessation is one of the most powerful measures to control mortality from this disease.3

Therefore, one of the ethical responsibilities of scientific societies is to provide health professionals with the best tools through guidelines and consensus so that they can offer the best care to patients who smoke.

The Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) prepared 2 documents of recommendations in 2003 and 2008 on the pharmacological treatment of smoking quitting.4,5 However, in the last fifteen years there have been important changes in the therapeutic approach to the disease, such as the appearance of new drugs like cytisine and the numerous studies on drug treatment optimization (clinical trials, observational studies, meta-analyses and systematic reviews) as well as its use in specific populations and circumstances.6 Varenicline and extended-release bupropion hydrochloride are temporarily withdrawn from the market. However, we have decided to include both treatments in this guide for the following reasons:

- A)

Varenicline is currently authorized for marketing outside the European Union.

- B)

Changes are being made in the formulation of varenicline that will allow it to be remarketed in Europe in the coming months.6

- C)

The reintroduction of extended-release bupropion is not ruled out soon.

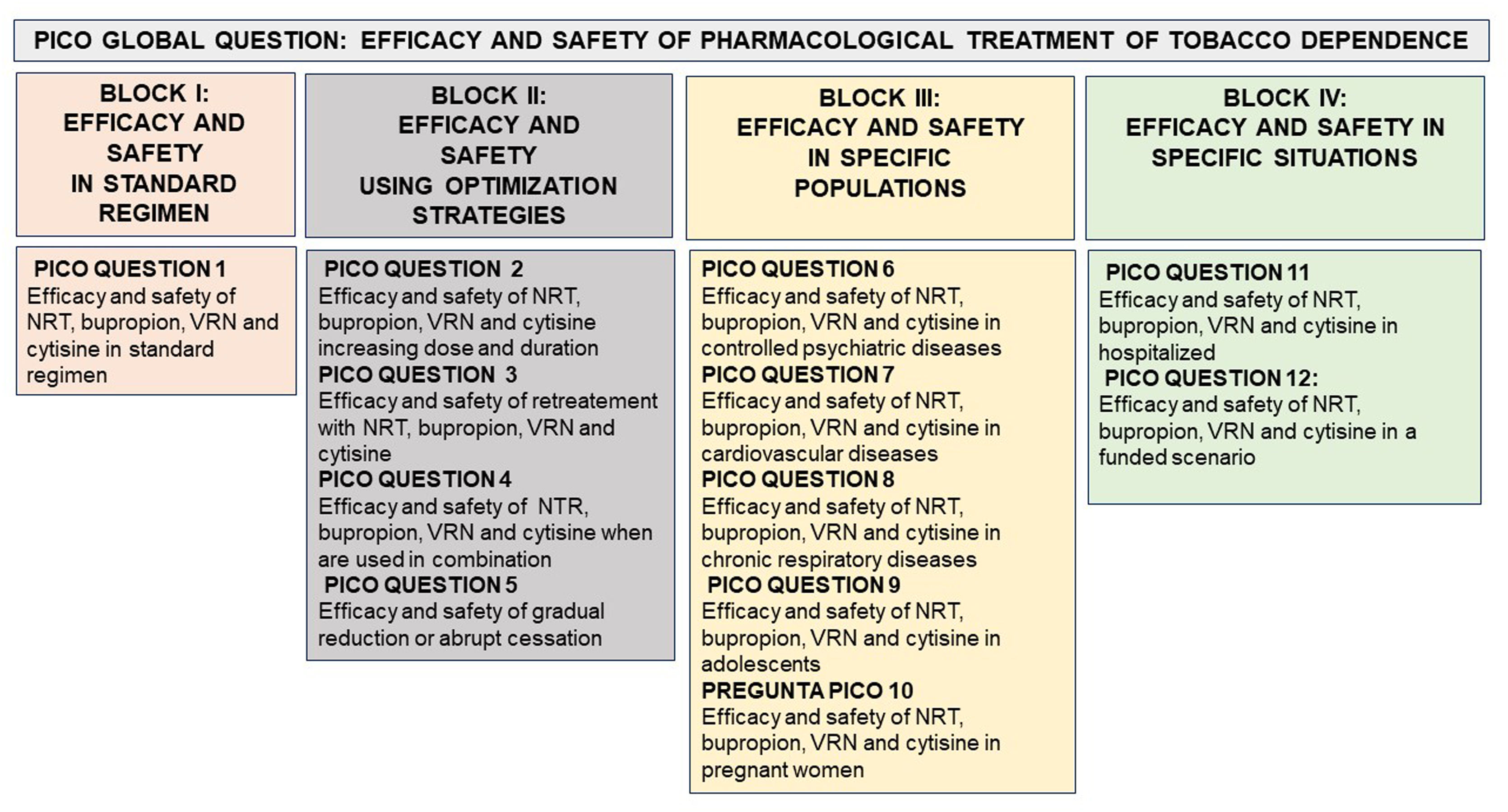

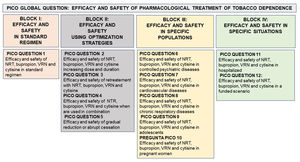

Thus, the main objective of this document is to provide all healthcare professionals in general and, in particular, those working in the field of smoking cessation with updated scientific information on some clinical questions relevant to the treatment of tobacco addiction. For all these reasons, we in the area of Tobacco Control proposed a document that attempts to answer a global PICO question (efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatment of tobacco dependence). From this, 12 PICO questions were generated, grouped in 4 thematic blocks: I. Efficacy and safety in standard regimen. II. Efficacy and safety using optimization strategies III. Efficacy and safety in specifics populations. IV. Efficacy and safety in specifics situations (Fig. 1).

Model of organization of the PICO questions based on a global PICO question (effectiveness and safety of pharmacological treatments for smoking). NRT: Nicotine replacement therapy. NRV: Varenicline. PICO or its variant PECO: Patient (Problem or Population), Intervention or Exposure, Comparison and Outcome (relevant outcome).

Based on the answers to these PICO questions, we made a pharmacological treatment proposal during the initial visit and in the follow-up process of the smoker who is quitting smoking.

MethodologyThis update document follows the SEPAR regulations regarding Treatment Guidelines. The elaboration of this guideline consists of the following phases.

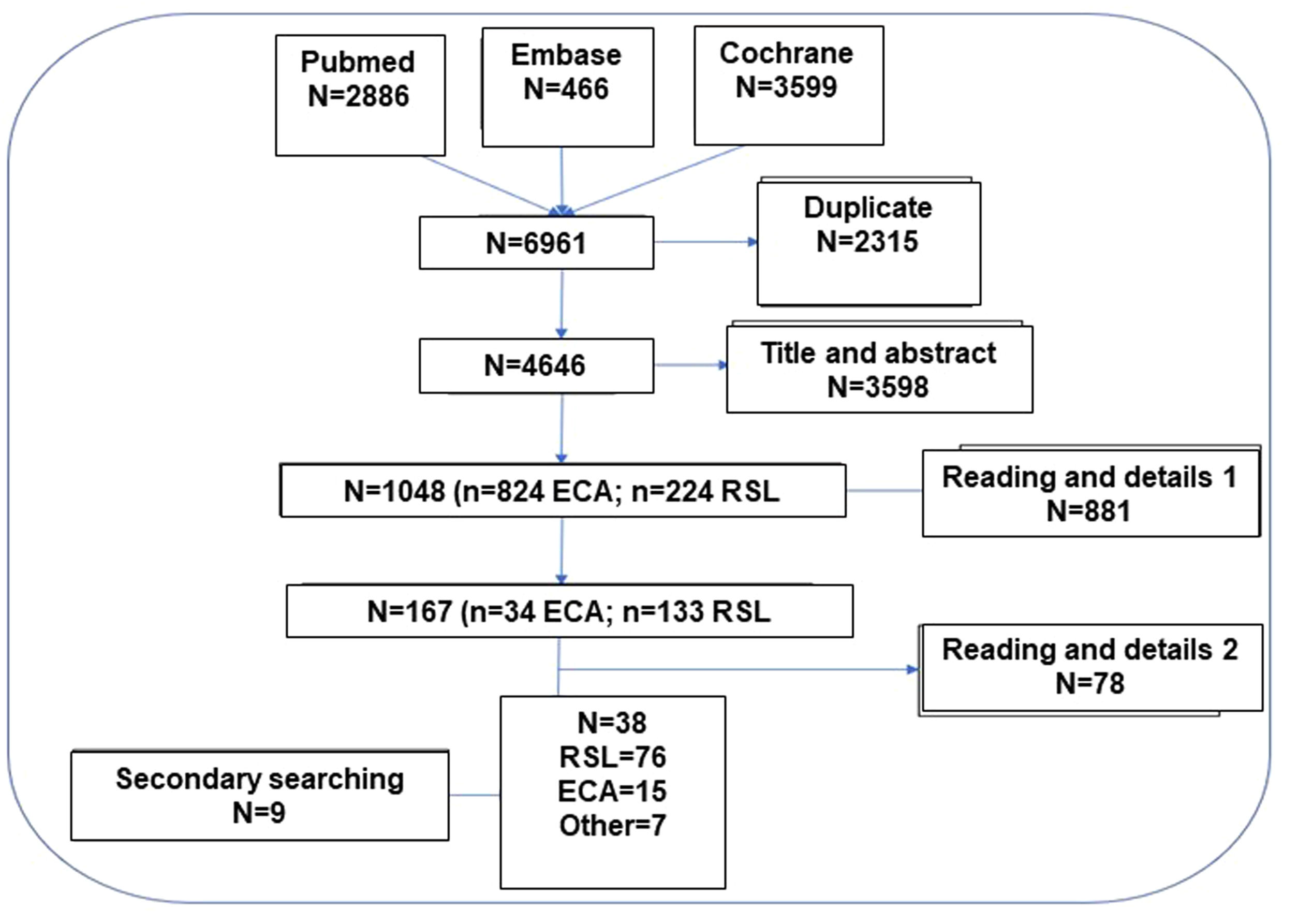

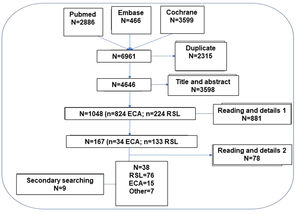

Formation of the guideline collaborating group and formulation of the clinical questions. Selection criteria and search strategyThe methodology was discussed in on-line meetings and the clinical scenarios to address the questions to be developed were selected. A first exhaustive search was carried out to define the feasibility of answering, based on scientific evidence, the questions initially posed; subsequently, the final questions to be answered were discussed and agreed upon (Fig. 1). In order to concentrate the search for the available evidence, all the clinical questions were transformed into the PICO format or its variant PECO: Patient (Problem or Population), Intervention or Exposure, Comparison and Outcome (relevant outcome).7 The bibliographic search strategy was performed simultaneously in 3 meta-search engines in the title of the article, abstract and keywords (descriptors) as well as terms in free text, with equivalent search fields in each database consulted: PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library (Tables 1MS, 2MS and 3MS of the supplementary material). As limits we searched only articles in humans, and in English or Spanish, but limiting the same until June 2022. The access protocol has not been registered.

Systematic literature review (SLR)The hierarchical SLR protocol was designed following the principles of the Cochrane Collaboration and PRISMA (see Fig. 2 and Table MS3).8,9 In a first step, 12 PICO questions mentioned in Fig. 1 were formulated.

Based on these, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were established: studies that included smoking population, regardless of duration, severity or other characteristics of smoking and smoking population (P); in treatment with varenicline, cytisine, bupropion or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) regardless of dose, duration or treatment strategy (I); studies with a placebo or active type comparator (C); that analyzed verified continuous abstinence (primary variable) or others such as adherence or patient satisfaction (O).

To evaluate the results obtained from the PICO questions, priority was given to selecting the highest level of evidence that best answered the clinical question, so that finally studies with the following designs were included: meta-analysis, SLR and randomized clinical trials (RCT).

In order to increase the reliability and safety of the process, the selected articles were independently assessed by 2 authors of the study to ensure their suitability to the object of the study and the inclusion criteria. When there were doubts about the inclusion of the article, the full text of the document was reviewed and if there was still a discrepancy between the 2 authors, a third author was incorporated to arbitrate the decision of inclusion or exclusion. A secondary manual search of the bibliography of the articles that were finally included was performed. Likewise, additional articles searched in nonstandard channels (gray, invisible, unconventional, fugitive, or semi-published literature) were added10 and, after their evaluation, were selected and documents identified in the articles collected in the search strategy were also added. The final selection of articles was done in a hierarchical manner, first selecting the SLRs that applied to each PICO question and then evaluating the RCTs (Fig. 2). Only those RCTs not included in the SLRs that provided new information were selected.

Therefore, the SLR excludes (a) opinion articles, duplicate articles, letters or editorials, (b) experimental (animal) or basic research studies, (c) clinical trials and systematic reviews that do not provide new information, (d) exclusion decision by the authors in articles that generate doubts or discrepancies, (e) articles with small sample size or absence of adequate conditions to verify smoking abstinence or absence of peer review.

The quality of the evidence was evaluated with the AMSTAR-2 (https://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php) for the SLRs and the Jadad scale11 for the RCTs. Evidence and results tables were generated. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system was used to rate the certainty of the estimated effects and the strength of the recommendations.

Nominal group meetingsThree nominal group meetings were held with the experts guided by a methodologist. In the first, the objectives, scope, users of the document and the PICO questions (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) were defined in order to carry out the SLR. Data were extracted from the titles, abstracts, key words or the complete article (in some cases from the supplementary material of the document), as appropriate, and in relation to the questions of interest. Likewise, possible individual biases were assessed in each study. In the second and third meetings, the results of the SLR were discussed and the treatment algorithms and specific recommendations for the defined population subgroups were agreed upon. In order to comply with the key aspects and appropriate steps to be considered when publishing an SLR in a biomedical journal, we adhered to the PRISMA statement (Table 3MS).8,9

ResultsPICO question 1: What is the efficacy and safety of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, varenicline and cytisine for the treatment of tobacco dependence?EvidenceThere are four drugs that are effective and safe for smoking cessation with level 1 scientific evidence: varenicline, NRT, bupropion and cytisine.

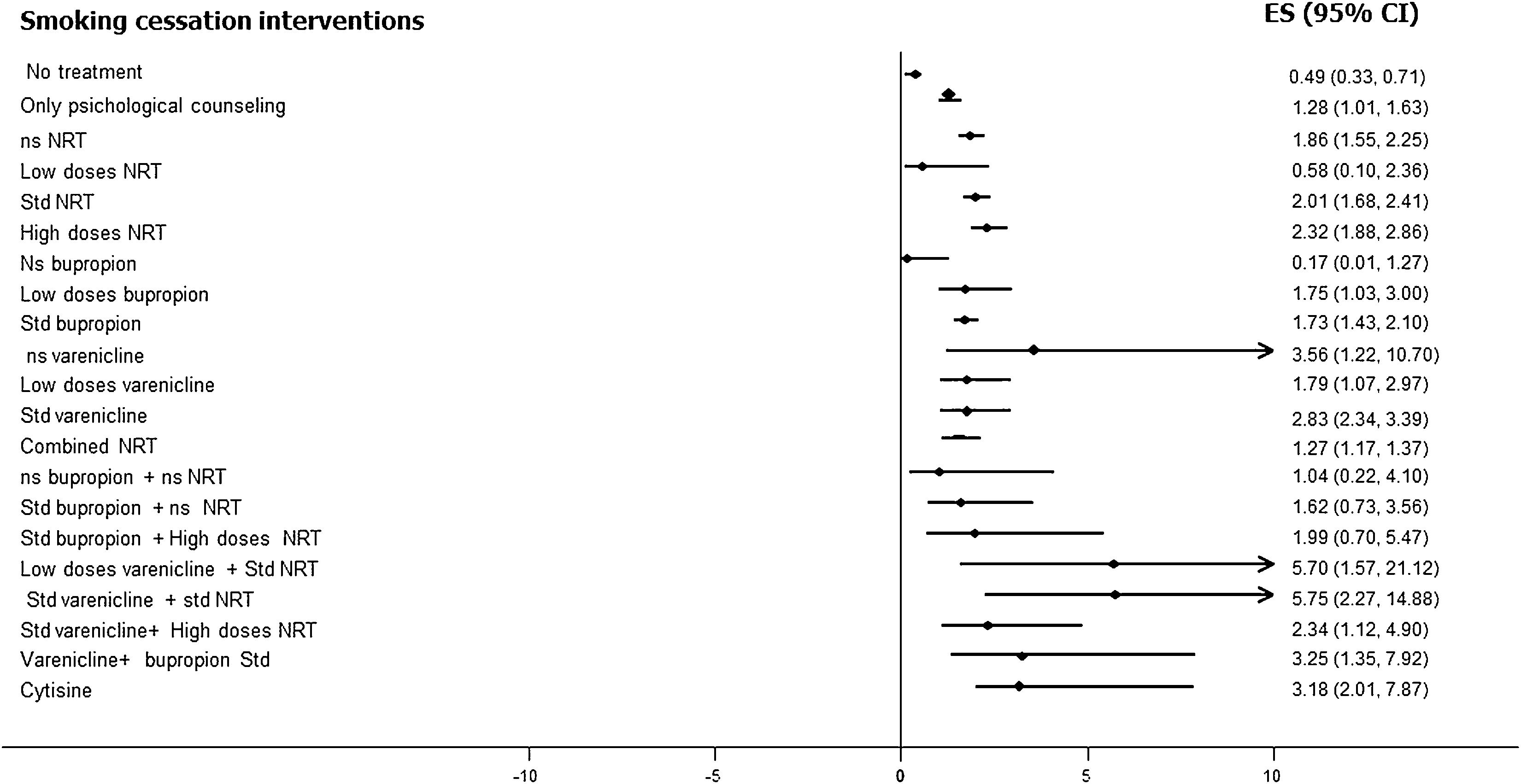

Varenicline, at standard doses and time, is safe and more effective than placebo. [OR: 2.83, 95% CI 2.34–3.39], level of evidence 1a.12–16

All types of NRT, at standard doses and time, are safe and more effective than placebo. [OR: 2.01, 95% CI 1.68–2.41], level of evidence 1a.14–19 It should be noted that, although no clear differences in safety and efficacy have been found between the different types of NRT, combined nicotine therapy (combined NRT), that is, administration of nicotine by two different forms, has been found to be safe and more effective than administration by a single form. [OR: 1.25, 95% CI 1.15–1.36], level of evidence 1a.14–19

Bupropion, at standard dose and time, has been shown to be safe and more effective than placebo [OR: 1.64, 95% CI 1.52–1.77, I2=15%], level of evidence 1a. It should be noted that its use causes a significant increase in mild adverse effects, but not in severe ones. [OR=1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.18, I2=64%], level of evidence 1a-b.14–16,18–21

Cytisine, at standard dose and time, has been shown to be safe and more effective than placebo, [OR=3.98, 95% CI 2.01–7.87, I2=0%], level of evidence 1b.12,13,22–25

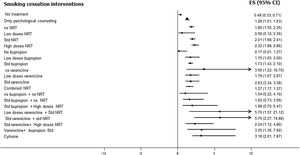

Fig. 3 shows the comparative efficacy data of different smoking cessation drugs in different meta-analyses. Of note, some of these studies are indirect comparisons.

Conclusions- 1.

Varenicline, NRT, bupropion and cytisine are safe and effective in aiding smoking cessation. Level of evidence 1a-b.

- 2.

Bupropion is associated with a higher number of mild adverse events than placebo. Level of evidence 1a-b.

- 3.

Comparatively between groups:

- 3.1

All types of NRT in monotherapy are of similar efficacy. Level of evidence 1b. Combined NRT is more effective than monotherapy NRT. Level of evidence 1a.

- 3.2

Varenicline is more effective than NRT monotherapy (level of evidence 1b), bupropion (level of evidence 1b), and cytisine (level of evidence 2a), but is not superior to combined NRT.

- 3.3

The efficacy of NRT in monotherapy is similar to that of bupropion. Level of evidence 2a.

- 3.4

Cytisine is more effective than NRT in monotherapy. Level of evidence 2a.

- 3.1

- -

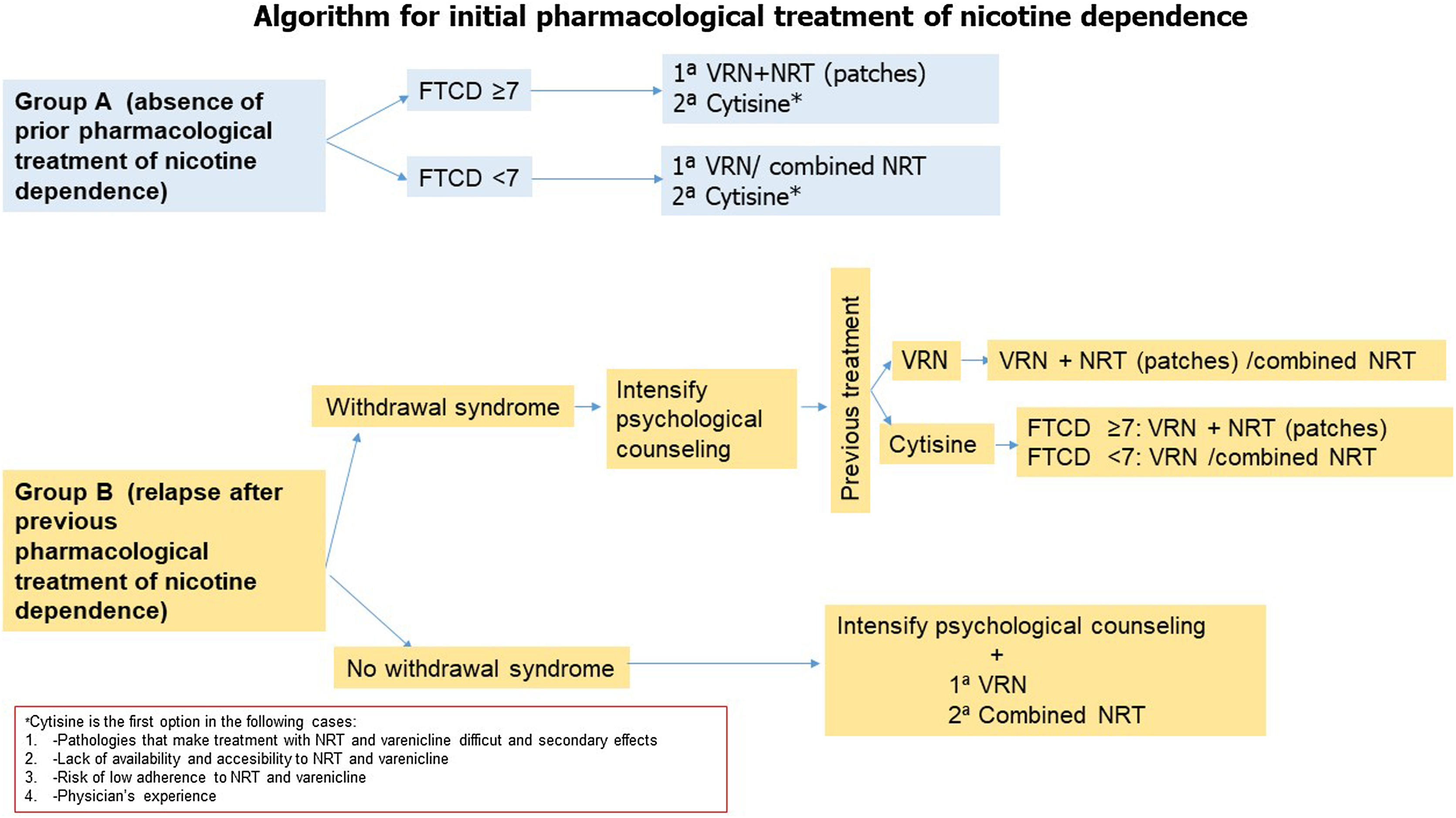

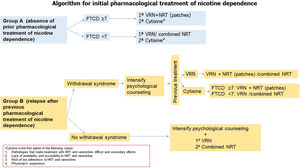

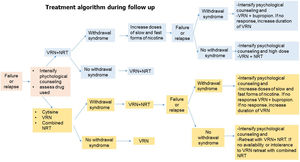

Algorithms 1 and 2 (Figs. 4 and 5) show the recommendations on the use of these drugs at different doses and timing as initiation and follow-up treatment in subjects who want to quit smoking.

Fig. 4.Algorithm 1. In a proposal for initiation of pharmacological treatment of smoking cessation, 2 groups of smokers are distinguished: group A (smokers who have not made previous quit attempts with treatment) and group B (smokers who have made previous attempts using drugs and have relapsed). In group A smokers, in patients with non-high physical dependence (FTND<7), the treatment of first choice is varenicline or combined nicotine replacement therapy. However, cytisine, despite presenting less scientific evidence of efficacy with respect to the previous, will be the first choice in the case of diseases in which the use of these drugs is contraindicated or in the situations shown in the figure. In patients with high nicotine dependence (FTND≥7), we propose as first choice varenicline plus nicotine replacement therapy (preferably nicotine patches), and as second choice cytisine if the previously mentioned criteria are met. In group B patients if the patient has previously relapsed due to abstinence syndrome, it is recommended to intensify psychological counseling and evaluate the drug used previously. If the patient was previously treated with varenicline, it is recommended to add nicotine patches. If the patient previously used combined NRT, it is recommended to add varenicline. In case of previous treatment with cytisine, if the patient presents a high physical dependence we recommend treatment with varenicline plus nicotine patches. In case of non-high nicotine dependence, varenicline or combined NRT will be considered. In case of previous relapse in patients who have been treated with drugs not due to abstinence symptoms, psychological counseling will be intensified and the first choice will be the combination of varenicline plus nicotine patches.

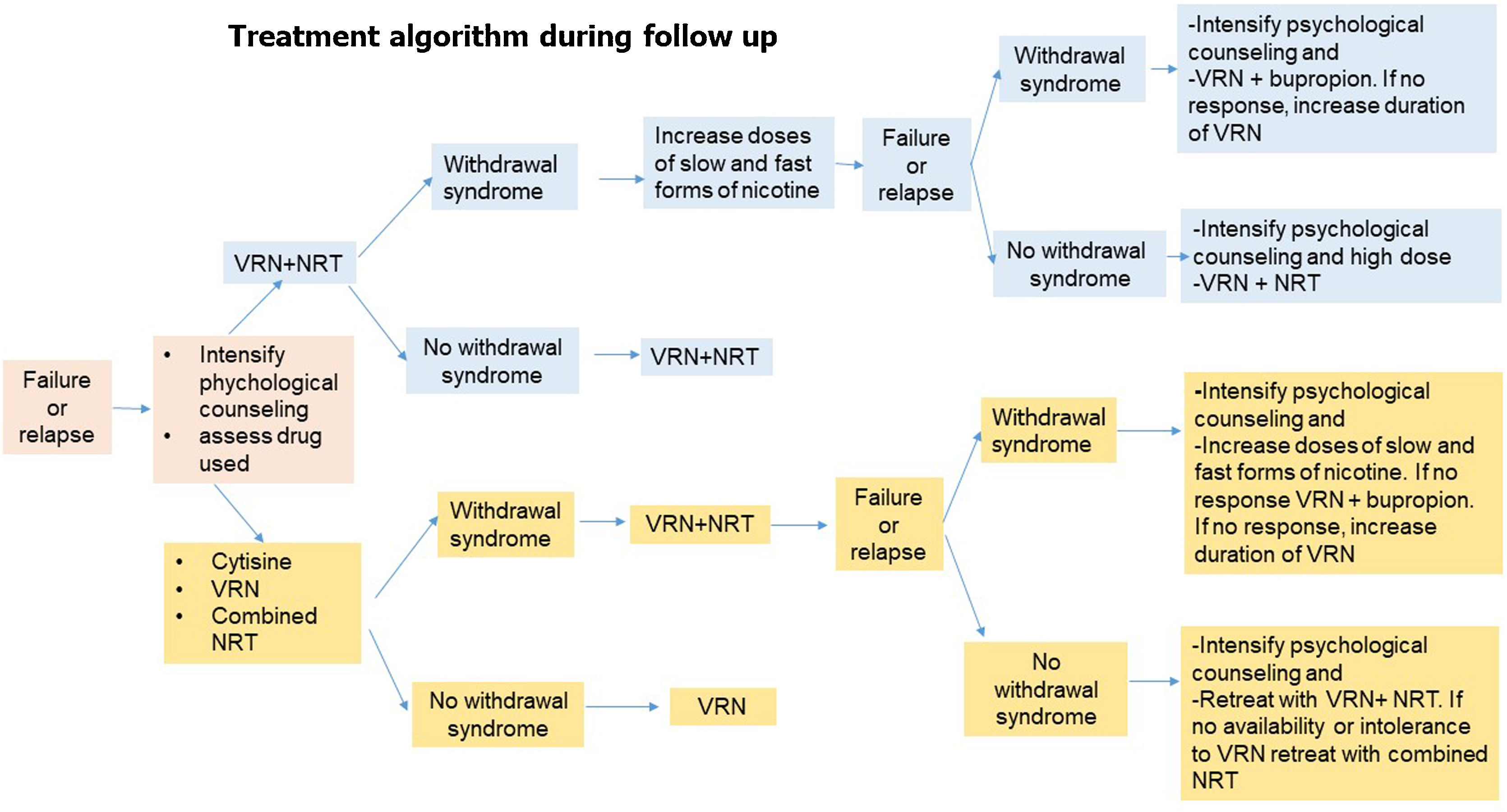

Fig. 5.Algorithm 2. During the follow-up process of smoking cessation in the event of failure or relapse, psychological treatment should be intensified, the cause of relapse and the drug used should be assessed. -If the relapse is caused by withdrawal syndrome and the patient was previously treated with varenicline plus NRT, the dose of nicotine should be increased in slow and fast forms. In case of failure or relapse as a consequence of withdrawal syndrome, despite these modifications, the combination will be changed, administering varenicline plus bupropion and if, despite this, there is no response, treatment with varenicline will be prolonged. If the patient relapses due to other causes than withdrawal syndrome, the combination of varenicline plus NRT will be repeated. -If the patient was previously treated with cytisine, varenicline or combined NRT if the cause of relapse was due to withdrawal syndrome, it is recommended to combined varenicline with NRT. If despite this combination the withdrawal syndrome persists, psychological counseling should be intensified and nicotine doses should be increased in slow and fast forms. If there is no response, a change of combination should be considered, preferably varenicline plus bupropion, and if, despite this, the patient continues to smoke, the use of varenicline should be prolonged. If the patient's relapse was not caused by withdrawal syndrome and the patient was previously treated with varenicline plus NRT, it is recommended to reinforce the combination of varenicline plus bupropion.

Although there is some discordant data, most studies suggest that prolonging varenicline treatment to 6 months is followed by a higher abstinence rate,15,16,18,26,27 level of evidence 2b-3a. The evidence is very weak with respect to increasing the dose of varenicline.15

In relation to NRT, higher dose patches have been found to achieve higher abstinence rates, without being associated with more safety issues, level of evidence 2a. In 24-h patches, the 21mg dose has been shown to be the most effective [OR=1.4, 95% CI 1.0–2.08]. In 16-h patches, the 25mg dose is the most effective [OR=1.19, 95% CI 1–1.41].17

The 4mg chewing gum is significantly more effective than the 2mg [OR=1.43, 95% CI 1.12–1.83, I2=67%], especially in smokers with a higher degree of dependence, level of evidence 2a.17

In relation to the duration of treatment with the patch, no significant differences have been found.17

With bupropion, no significant differences were found between 150mg and 300mg per day. [OR=1.08, 95% CI 0.93–1.26, I2=49%] with no differences in safety, level of evidence 1b.21

With cytisine there are some preliminary studies showing that the highest short-term abstinence rate was obtained with the 3mg dose, level of evidence 2b-3a.28,29

Conclusions- 1.

Regarding NRT:

- 1.1

Patches at higher than standard doses are more effective without causing safety problems. Level of evidence 2a.

- 1.2

4mg chewing gum is more effective than 2mg and does not cause safety problems, especially in smokers with a higher degree of dependence. Level of evidence 2a.

- 1.1

- 2.

With bupropion, no differences in efficacy or safety have been shown between 150 and 300mg per day. Level of evidence 1b.

- 3.

Cytisine could be more effective at higher doses and for a longer time without major safety problems. Level of evidence 2b-3a.

- 4.

Varenicline could be more effective when treatment is prolonged for 24 weeks. Level of evidence 2b.

- -

Algorithms 1 and 2 (Figs. 4 and 5) show the recommendations on the use of these drugs at different doses and time as initiation and follow-up treatment in subjects who want to quit smoking.

Retreatment with NRT consisting of using different forms of nicotine after previous use of nicotine patches has demonstrated abstinence rates of 0–6.4% with no adverse effects observed, level of evidence 3a-b.30–32

Retreatment with bupropion for 12 weeks was studied in a randomized clinical trial of moderate quality, showing abstinence rates at 6 and 12 months of 12 and 9% respectively, being significantly superior to placebo, level of evidence 2b-3a. Another evaluated abstinence at 6 months with repeated cycles of bupropion, being higher than 10%. No adverse effects were recorded in any of the cases.33,34

Retreatment with varenicline in a quality double-blind placebo-controlled RCT on nearly 500 smokers with ≥1 previous quit attempt (≥2 weeks) demonstrated a continuous abstinence rate during weeks 9–12 of 45% vs. placebo 11.8%, [OR=7.08, 95% CI 4.34–11.55] with no serious adverse events reported, level of evidence 1b-2a.35

We do not have data on retreatment with cytisine.

Conclusions- 1.

Retreatment with NRT and bupropion at standard dose and regimen could be effective and safe, but the magnitude of effect is small. It cannot be ruled out that at higher doses of NRT the level of efficacy is higher. Level of evidence 3a-b.

- 2.

With the current evidence, retreatment with varenicline is effective and safe with a relevant magnitude of effect. Level of evidence 1b-2a.

- -

In patients who have previously used varenicline for more than 2 weeks and relapse, we recommend retreatment with this drug.

The efficacy and safety of the combination of first-line drugs (varenicline plus NRT, varenicline plus bupropion and NRT plus bupropion) is analyzed in several studies.12–16,18,19,21,36–39 An SLR and network meta-analysis, which included 20 RCTs of moderate quality and more than 16,000 smokers, showed that compared to placebo and monotherapies, short- and long-term continuous abstinence is higher with combination treatments, without major safety issues, level of evidence 2a. The most effective combination was varenicline plus bupropion [OR=6.08, 95% CI 3.47–10.66], which was superior to varenicline plus NRT [OR=1.66, 95% CI 1.07–2.59] and to monotherapies.15

Another SLR with network meta-analysis found that compared with placebo, the greatest efficacy was obtained with standard varenicline plus standard NRT [OR=5.75, 95% CI 2.27–14.88], followed by low-dose varenicline plus standard NRT [OR=5.70, 95% CI 1.57–21.12]. Another SLR also demonstrates greater efficacy with varenicline plus NRT without an increased risk of serious adverse events, level of evidence 2a.16,18 Recently, a review did not find greater efficacy when bupropion was combined with NRT or varenicline, but did find an increase in adverse events.21 On the other hand, consensus documents are in favor of combinations in a profile of smokers with high dependence (FTND≥7), very high smoking (>30cigarettes/day) and previous unsuccessful quit attempts with drugs, being the combination of choice varenicline plus NRT.39

Conclusions- 1.

Great heterogeneity and complexity of the analysis of combined therapies, since indirect comparisons are necessary to obtain an overall picture of all the possibilities.

- 2.

Combination therapy is significantly superior to placebo and monotherapies, at least in the short-medium term. Level of evidence 2a.

- 3.

Combinations that include varenicline are superior to others. Probably the most effective is that of varenicline plus NRT. Level of evidence 2a. The magnitude of the effect is more evident in heavy smokers and in those with a higher level of dependence. Level of evidence 2a.

- 4.

No robust evidence found for combinations with cytisine.

- 5.

Combination has not been shown to be associated with increased risk of serious adverse events. Level of evidence 1b-2a.

- -

In patients with a higher degree of smoking and dependence, we recommend a combination of first-line drugs versus monotherapy being the combination varenicline plus NRT the most effective.

Recently, in a study of 51 RCTs comparing the efficacy of gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation, no difference was found in the rate of verified continued abstinence [OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.87–1.17, I2=29%, n=22 studies], level of evidence 1b-2a. However, in subgroup analyses, if gradual reduction was associated with pharmacological treatment, this could be more effective in achieving abstinence than abrupt cessation, although with high heterogeneity [OR=1.68, 95% CI 1.09–2.58, I2=78%, n=11 studies], level of evidence 1b. This was observed with varenicline [OR=1.48, 95% CI 1.16–1.9] (n=1 study) (level of evidence 3a), and with rapid-acting NRT [OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.93–3.39, I2=0%] (n=7 studies). There was also no difference between these strategies whether or not a fixed quit date was established, different durations of the reduction period, or with a structured cessation program [OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.93–3.39, I2=0%] (n=7 studies), or with a structured cessation program [OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.93–3.39, I2=0%] (n=7 studies), level of evidence 3b.

There were also no differences between these strategies with or without a fixed quit date, different lengths of the reduction period, or with or without a structured smoking reduction program.27,40 In patients not ready to quit smoking, the evidence is similar and gradual reduction is considered a valid way to proceed.41,42

Recommendations- -

There is insufficient evidence to consider one strategy superior to the other (NE 1b-2a).

- -

If tapering is coupled with pharmacological treatment (varenicline and rapid-acting NRT), higher abstinence rates would be achieved than with abrupt cessation. Level of evidence 2a.

Several SLRs (some with meta-analyses) have been published analyzing efficacy and safety in these patients, including the most severe1–6,43–48; the latest review from 2022 analyzes 19 observational studies in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression.43 The following recommendations can be drawn from the analysis of these reviews.

Recommendations- -

NRT, bupropion and varenicline are effective, also in patients with more severe disease, without these treatments interfering with the course of the underlying disease. They have not been associated with serious neuropsychiatric adverse events including suicide and suicidal ideation. Level of evidence 2b-4.6–8,48–50

- -

Flexible and individualized multicomponent treatments improve outcomes, especially those associated with more intense cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT). Level of evidence 3a-4.

- -

In patients with schizophrenia, the efficacy of varenicline is superior to bupropion, but similar to NRT. Level of evidence 3a.

- -

In patients with major depression, NRT was effective in the short term, varenicline and combinations of CBT with bupropion and NRT were effective in the long term. Level of evidence 2a-4.

- -

There is no evidence on efficacy and safety of cytisine.

In cardiovascular patients the evidence comes from the analysis of SLRs (the latest in 2021) and RCTs12,13,51–60 with moderate quality of the studies with variability in the type and severity of diseases included.

Recommendations- -

In the medium to long term, NRT, bupropion, especially in patients with stable pathology, and also varenicline (level of evidence 2a) are effective.

- -

In indirect comparisons, varenicline and NRT combined were superior to NRT monotherapy and bupropion. Level of evidence 3a.

- -

NRT, bupropion, and varenicline have not been associated with increased medium- or long-term cardiovascular adverse events in patients with cardiovascular disease. Level of evidence 2a.

- -

There is no evidence on efficacy and safety of cytisine.

Several systematic reviews (some with meta-analysis) are analyzed.61–76 Basically, they focus on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)61–71 and others on subjects with asthma.72–74 In addition, recommendations from scientific societies have been considered.75,76

The use of combined and/or high-dose NRT has been found to be safe and more effective than placebo in helping COPD patients to quit smoking at 6 and 12 months follow-up. [OR: 2.60, 1.29–5.24], level of evidence 1b. Data for varenicline showed similar results [OR=3.34, 1.88–5.92], level of evidence 1b. However, for bupropion, efficacy was only found at 6-month follow-up [OR=2.03, 1.26–3.28], level of evidence 1b.61–71,74,75 The recommendations of the societies express the need for the association of aggressive pharmacotherapy with intense psychological counseling for the treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with COPD.75,76

Fewer studies are available in smokers with asthma, but both varenicline and combined NRT have been shown to be effective and safe in helping this group of subjects to quit smoking. Level of evidence 2b-3a.72–74 No studies have been conducted with cytisine.

Recommendations- -

The use of varenicline or combined NRT is recommended as the first option for the treatment of smoking in smokers with COPD. Bupropion could be used as a second option. The use of varenicline or combined NRT or NRT at high doses and/or prolongation of the use of these drugs, as well as the use of combined treatments (varenicline plus nicotine patches) together with intensified psychological counseling can be a good therapeutic option in this group of subjects.

- -

For asthmatic smokers, it is recommended to use combined NRT or varenicline as the first option.

NRT is no more effective than placebo [OR=1.11, 95% CI 0.48–2.58, I2=20%], level of evidence 1b-2a) or counseling [OR=0.15, 95% CI 0.01–2.94], level of evidence 2b76,77 with no difference between patches and gum at 6 months. In the short term, patches (28%) are more effective than chewing gum (6%).77

Bupropion is not more effective than placebo [OR=1.49, 95% CI 0.55–4.02], in monotherapy or associated with nicotine patch [OR=1.05, 95% CI 0.41–2.69], level of evidence 2b.78

Varenicline is not more effective than placebo, level of evidence 1b-2a. There are no data on efficacy and safety of cytisine.79,80

Side effects of all treatments were mild.77–80

Recommendations- -

Drugs are less effective for smoking cessation in adolescents.

- -

Cognitive-behavioral interventions should be intensified, adapted to the characteristics of their age and involving parents/legal guardians.

NRT is more effective than placebo or behavioral therapy in maintaining abstinence during pregnancy [OR=1.37, 95% CI 1.08–1.74, I2=34%] and postpartum [OR=1.22, 95% CI 0.84–1.77], but not at 12 months [OR=1.04, 95% CI 0.57–1.88], level of evidence 1b-2a.81–84

NRT during the first trimester is safe for the fetus, level of evidence 1b-2b.81–85 During the 2nd and 3rd trimester it could have effects similar to tobacco exposure, level of evidence 1b-2b82 without evidence of serious complications for the fetus (level of evidence 2a),81,82,84,86 infant (level of evidence 2b-3a),81 or pregnant (level of evidence 1b).81

Bupropion is not more effective than placebo or behavioral therapy [OR=0.74, 95% CI 0.21–2.64], level of evidence 2a-b.81 It may increase cardiovascular birth defects, level of evidence 4, but not miscarriage, prematurity, or low birth weight, level of evidence 2b-3a.86–88

Varenicline has not shown adverse effects on the fetus, level of evidence 486,88 Cytisine is contraindicated in pregnant women.

Recommendations- -

The treatment of choice is intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy. NRT can be used if it fails,

- -

assessing risk–benefit, preferably during the first trimester.

- -

The first option is the fast-acting forms (chewing gum or tablets) and the second option is 16-h and 15mg patches.

- -

Bupropion, varenicline, and cytisine should be avoided because of the limited evidence on their safety.

Smoking is one of the main causes of disease leading to hospitalization. Cardiovascular, respiratory and tumor diseases are among the main causes of hospital admission. Different reasons support hospitalization as an ideal time to encourage smoking cessation in patients who smoke.

The published scientific evidence focuses on some SLRs with quality meta-analyses:

The 2012 Cochrane review55 included more than 50 RCTs of heterogeneous quality, concludes that: (1) intensive cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) (which included intensive advice/counseling during admission and supportive contacts for at least one month after discharge) was associated with higher rates of verified continuous abstinence compared to placebo [OR: 1.37, 95% CI 1.27–1.48, I2=37% (n=25 studies)] (2) The efficacy when adding NRT to ICBT was significantly superior to intensive intervention without the drug [OR: 1.54, 95% CI 1.34–1.79 (n=6 studies)]. This benefit was not observed when adding varenicline or bupropion, which in the latter case also coincided with that observed by Grandi et al., 2013.52 (Level of evidence 2a). No adverse events are reported in the subgroups of patients studied, including cardiovascular events; in this subgroup, 1 RCT showed that ICBT plus drugs is accompanied by a reduction in mortality rates in the two years following the intervention.

Subsequently, several RCTs of moderate quality have been published that have shown that varenicline is the drug that achieves the highest rate of continued abstinence at 12 months in hospitalized patients.55,89,90

Recommendations- -

The use of NRT with NRCT in hospitalized patients with subsequent follow-up (in the first 4 weeks after discharge) is effective and safe. Level of evidence 1a-b.

- -

Currently, there is insufficient evidence regarding the combined use of CCT with bupropion. Level of evidence 2a. There are no studies with cytisine.

- -

Varenicline monotherapy is effective in hospitalized patients. Level of evidence 2b.

The scientific evidence collected in the 2017 Cochrane SLR91 objectified that funding (full or partial) of pharmacological treatment for tobacco dependence increases verified continuous abstinence at 6 months [OR: 1.77 95% CI 1.37–2.28, I2=33% (n=9333 patients)]. Funding of smoking cessation treatment leads to more smokers making quit attempts and more of them using them in the attempt and, consequently, to more smokers quitting smoking, thereby increasing the efficiency and cost/benefit of these drugs (Table 1).92–95

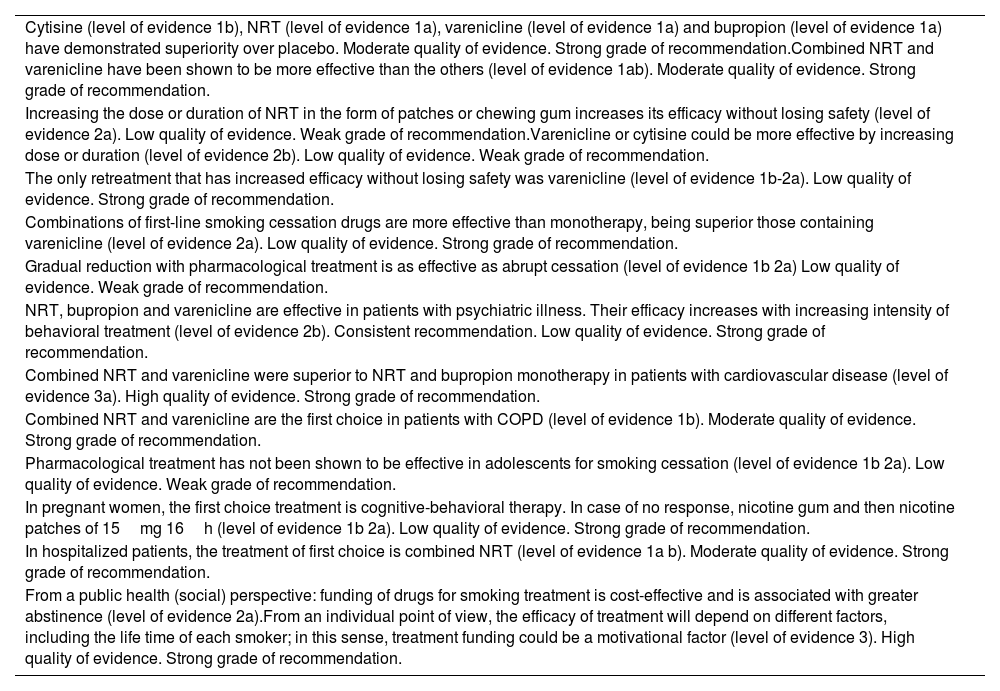

Shows the recommendations for pharmacological treatment of smoking cessation using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system to rate the certainty of the estimated effects and the strength of the recommendations.

| Cytisine (level of evidence 1b), NRT (level of evidence 1a), varenicline (level of evidence 1a) and bupropion (level of evidence 1a) have demonstrated superiority over placebo. Moderate quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation.Combined NRT and varenicline have been shown to be more effective than the others (level of evidence 1ab). Moderate quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Increasing the dose or duration of NRT in the form of patches or chewing gum increases its efficacy without losing safety (level of evidence 2a). Low quality of evidence. Weak grade of recommendation.Varenicline or cytisine could be more effective by increasing dose or duration (level of evidence 2b). Low quality of evidence. Weak grade of recommendation. |

| The only retreatment that has increased efficacy without losing safety was varenicline (level of evidence 1b-2a). Low quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Combinations of first-line smoking cessation drugs are more effective than monotherapy, being superior those containing varenicline (level of evidence 2a). Low quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Gradual reduction with pharmacological treatment is as effective as abrupt cessation (level of evidence 1b 2a) Low quality of evidence. Weak grade of recommendation. |

| NRT, bupropion and varenicline are effective in patients with psychiatric illness. Their efficacy increases with increasing intensity of behavioral treatment (level of evidence 2b). Consistent recommendation. Low quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Combined NRT and varenicline were superior to NRT and bupropion monotherapy in patients with cardiovascular disease (level of evidence 3a). High quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Combined NRT and varenicline are the first choice in patients with COPD (level of evidence 1b). Moderate quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| Pharmacological treatment has not been shown to be effective in adolescents for smoking cessation (level of evidence 1b 2a). Low quality of evidence. Weak grade of recommendation. |

| In pregnant women, the first choice treatment is cognitive-behavioral therapy. In case of no response, nicotine gum and then nicotine patches of 15mg 16h (level of evidence 1b 2a). Low quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| In hospitalized patients, the treatment of first choice is combined NRT (level of evidence 1a b). Moderate quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

| From a public health (social) perspective: funding of drugs for smoking treatment is cost-effective and is associated with greater abstinence (level of evidence 2a).From an individual point of view, the efficacy of treatment will depend on different factors, including the life time of each smoker; in this sense, treatment funding could be a motivational factor (level of evidence 3). High quality of evidence. Strong grade of recommendation. |

- -

From a public health (social) perspective: the financing of drugs for the treatment of smoking cessation is cost-effective and is associated with greater abstinence. Level of evidence 2a.

- -

From an individual point of view, the efficacy of treatment will depend on different factors, including the life time of each smoker; in this sense, treatment financing could be a motivational factor. Level of evidence 3.

All authors contributed equally to the conception, writing, revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Ethical aspectsThis document was authorized and promoted by the Governing Boarding of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) and Document Management Committee.

Financial disclosureNone of the authors have received funding.

Conflict of interestsCR-C has received honoraria for speaking engagements, sponsored courses, and participation in clinical studies from Aflofarm, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva.

JIG-O has received honoraria for speaking, scientific consulting, clinical study participation, or publication writing for the following: Astra-Zeneca, Chiesi, Esteve, Faes, Gebro, Menarini, and Pfizer.

JAR-M has received scientific consulting and/or speaking fees from Aflofarm, Astra-Zeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Rovi, and Teva.

EH-M has received fees for presentations, conferences and courses sponsored by: Astra-Zéneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, Esteve, Faes Farma, Ferrer, GSK, Mundiphasrma, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer and Rovi.

EC-C declares that she has no conflict of interest.

JS-CM has received fees for presentations, participation in clinical studies and publications by: Aflofarm, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer, Ferrer, GSK, Menarini, Pfizer and Rovi.

MG-R declares that he has no conflict of interest.

EP-E has received fees for presentations and collaborations for training from: Aflofarm, Bial, Chiesi, Faes, Ferrer, Novartis and Pfizer.

CAJ-R has received honoraria for presentations, participation in clinical studies and consultancy from: Aflofarm, Bial, GSK, Menarini and Pfizer.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all the cited authors. In addition, we confirm that the order of authors that appears in the manuscript has been approved by all. On the other hand, we have given due consideration to the protection of individual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to its publication.

We understand that the author of the correspondence is the only contact for the editorial process. We confirm that we have provided a current and correct email address, that it is accessible by the corresponding author and that it has been configured to accept email from crabcas1@gmail.com.