Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is an irreversible disease with fatal progression and high mortality.1,2 Its debilitating symptoms, especially cough, dyspnea, and fatigue, progressively impair quality of life (QoL).3,4 Current recommended treatment includes a pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic approach.1,5

Nintedanib and pirfenidone slow disease progression,1,5 thereby extending life expectancy.3 However, both drugs associate adverse events (AEs) that may interfere with nutritional status (diarrhea, nausea, appetite loss)2 and medication compliance.6 Optimizing the antifibrotic effect over time requires prevention and managing potential drug side effects while maintaining QoL.5,7

An integral approach to IPF patients, addressing all the patient's multidimensional and complex care needs, requires multidisciplinary team-based care.8 However, this approach remains challenging and considers emotional state, physical activity, drug optimization, comorbidities, and adapting holistic care to patient needs.9–11

Patient support programs (PSPs) improve medication adherence and QoL, and the specialized nurse in interstitial lung disease (ILD) is crucial.12–14 However, most PSPs lack the integral approach that IPF patient-centered care requires. Therefore, we designed an IPF integral PSP (iPSP) over 12 months, based on homecare visits carried out by specialized nurses and physiotherapists.

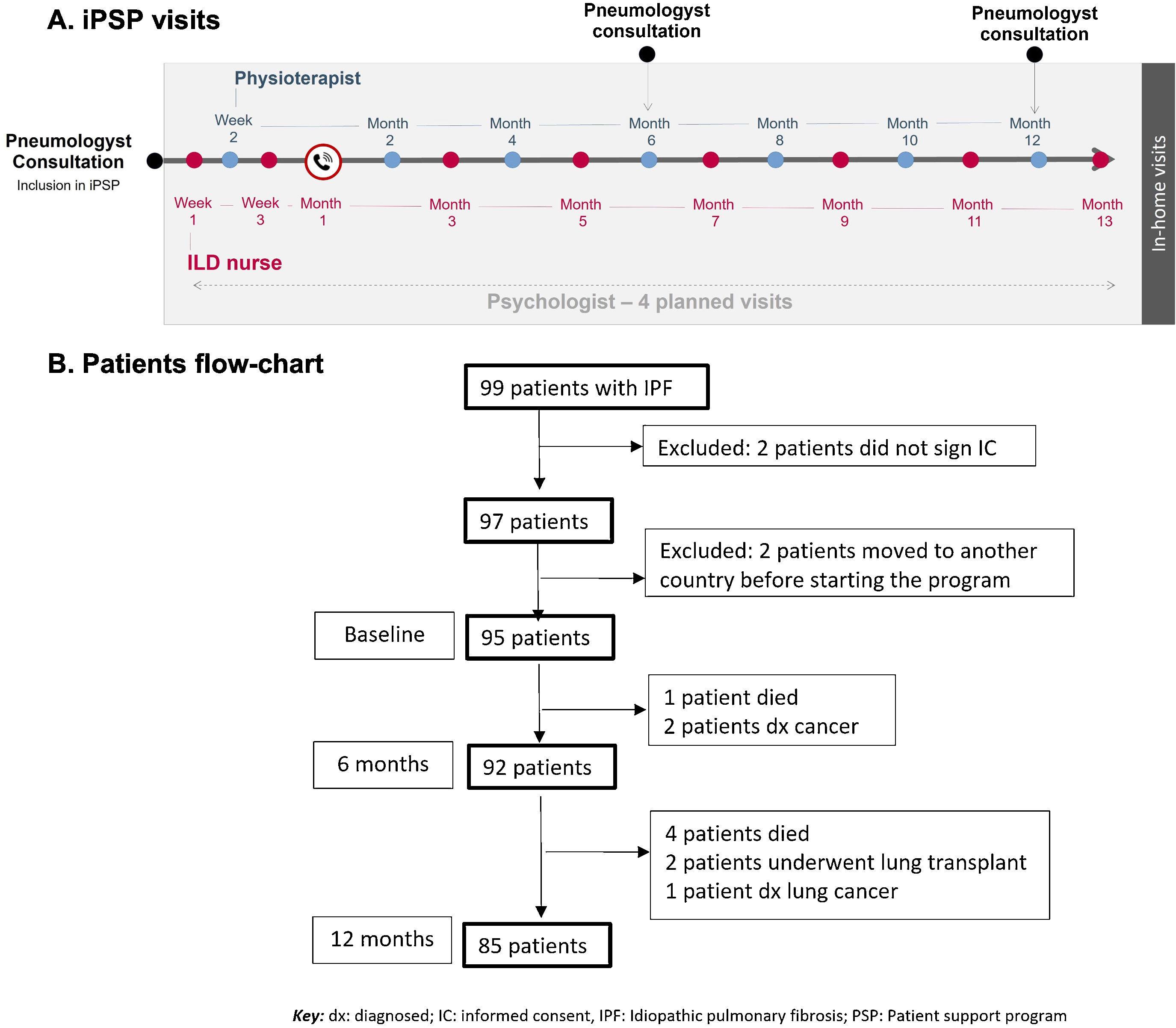

The integral PSP was designed for all IPF patients diagnosed within the previous three years, with a forced vital capacity [FVC]>50% and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide [DLCO]>30%, who had been started on nintedanib treatment at least 1 month ago. The iPSP (NCT05173571) was approved by Bellvitge University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (PR118/18). Patients were included after signing the informed consent. Patients received in-home visits over 12 months from trained nurses and physiotherapists (Fig. 1A). Visits were performed by ILD nurses the first month (weeks 1 and 3, plus a phone-call at week 4), and from then on, one visit every other month (months 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13), alternating with the physiotherapist visits (week 2 and months 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). An expert psychologist trained the iPSP team in communication abilities and coaching, and he was asked for visiting patients at any time according to the patient's need for psychotherapy. The ILD nurses carried out interventions focused on: training (patient education on disease and medication for improving patient-empowerment), reviewing (medication compliance/dose adjustments and diet [including nutritional counseling]), and controlling (respiratory infections and vaccine plan). Moreover, they provided emotional support and management. On the other hand, the physiotherapists provided an individualized care plan including therapeutic and respiratory exercises, and both manual and instrumental techniques aimed to, among others: increase the thoracic mobility and the maximal inspiratory flow/capacity, improve, and maintain the function of respiratory muscles, and re-educate the respiratory pattern when needed.

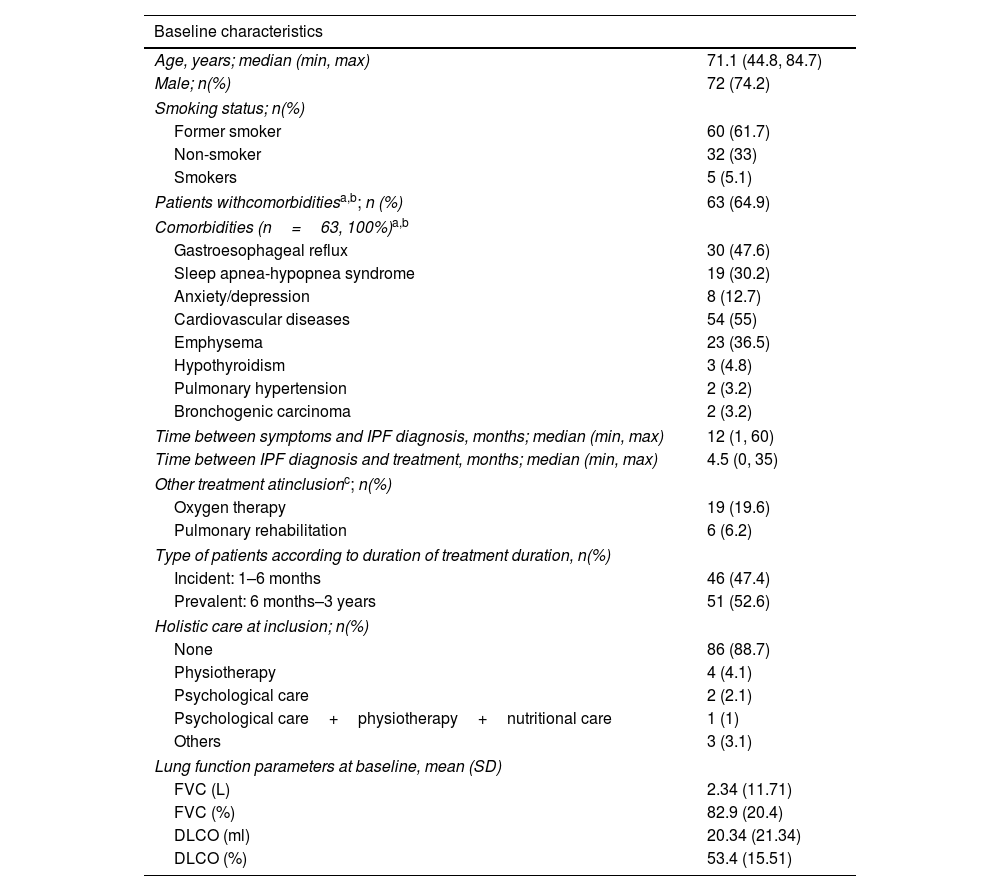

(A) Scheduled visits of integral Patients Support Program (PSP). The ILD nurses carried out interventions focused on patient education on disease and medication, reviewing medication compliance/dose adjustments and diet, and provided emotional support. The physiotherapists provided an individualized care plan including respiratory exercises and techniques aimed to increase thoracic mobility and maximal inspiratory flow/capacity, respiratory muscle function, and re-educate the respiratory pattern when needed. (B) Patients with IPF included in the integral PSP (flowchart).

The primary objective was to maintain the QoL of IPF patients over 12 months, measured by the King's Brief Interstitial Lung Disease (K-BILD) questionnaire. In addition, other QoL aspects were also evaluated through the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (EQ-VAS and EQ-5D), the IPF-specific version of St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ-I), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The secondary objectives included: hospitalizations, dyspnea (Borg and modified medical research council [mMRC] scales), respiratory muscle strength (maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures [MIP/MEP]), and exercise capacity (six-minutes walking test [6MWT, at pneumologist consultation] and the six-minutes stepper test [6MST], at home15). Patients’ satisfaction with the iPSP was also assessed. Disease progression was considered if a decline of FVC>10% and/or DLCO>15% was observed.

Mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum–maximum were used for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical ones. Paired t-test, R paired Wilcoxon test, paired McNemar–Bowker, and Chi-square test were used for comparing variables. Interpolation or extrapolation was not used for assigning or estimating the missing values. The statistical analysis was performed at 6 and 12 months by using SPSS software. P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. A K-BILD total score difference equal, higher, or lower than 5 was considered clinically significant.16

Ninety-nine consecutive patients from 22 Spanish hospitals were approached (December 2018–July 2019), and ninety-seven were enrolled (two patient did not sign the informed consent) (Fig. 1B). Two patients moved to another country before starting the program. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1A.

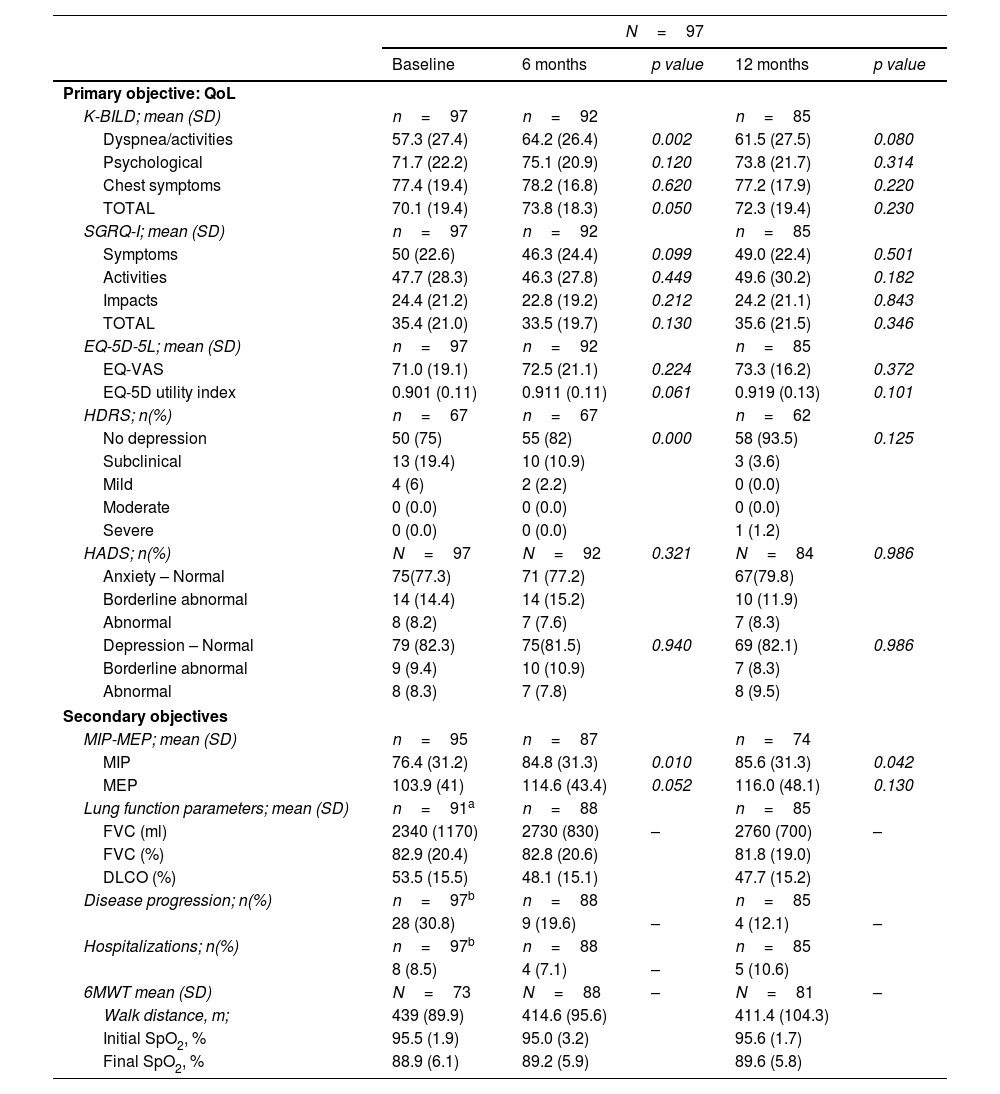

Patient features. Baseline characteristics of the patients included in the iPSP.

| Baseline characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, years; median (min, max) | 71.1 (44.8, 84.7) |

| Male; n(%) | 72 (74.2) |

| Smoking status; n(%) | |

| Former smoker | 60 (61.7) |

| Non-smoker | 32 (33) |

| Smokers | 5 (5.1) |

| Patients withcomorbiditiesa,b; n (%) | 63 (64.9) |

| Comorbidities (n=63, 100%)a,b | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 30 (47.6) |

| Sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome | 19 (30.2) |

| Anxiety/depression | 8 (12.7) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 54 (55) |

| Emphysema | 23 (36.5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (4.8) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2 (3.2) |

| Bronchogenic carcinoma | 2 (3.2) |

| Time between symptoms and IPF diagnosis, months; median (min, max) | 12 (1, 60) |

| Time between IPF diagnosis and treatment, months; median (min, max) | 4.5 (0, 35) |

| Other treatment atinclusionc; n(%) | |

| Oxygen therapy | 19 (19.6) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 6 (6.2) |

| Type of patients according to duration of treatment duration, n(%) | |

| Incident: 1–6 months | 46 (47.4) |

| Prevalent: 6 months–3 years | 51 (52.6) |

| Holistic care at inclusion; n(%) | |

| None | 86 (88.7) |

| Physiotherapy | 4 (4.1) |

| Psychological care | 2 (2.1) |

| Psychological care+physiotherapy+nutritional care | 1 (1) |

| Others | 3 (3.1) |

| Lung function parameters at baseline, mean (SD) | |

| FVC (L) | 2.34 (11.71) |

| FVC (%) | 82.9 (20.4) |

| DLCO (ml) | 20.34 (21.34) |

| DLCO (%) | 53.4 (15.51) |

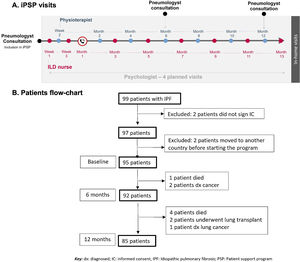

QoL assessment. The main objective, maintaining quality of life from baseline to 12 months, was achieved: QoL questionnaires showed similar total scores at both time-points (Table 1B). Furthermore, a significant improvement in K-BILD's total score was observed at 6 months from baseline (p=0.05), especially due to the domain of “dyspnea and activities” (p=0.002) (Table 1B). In this domain, a clinically significant improvement (increase>5 points) was achieved in 18 patients (22.6%). The difference in K-BILD's total score was present regardless of age, gender, or incident/prevalent cases, although a greater improvement was present in patients older than 65 years, also in incident cases or those that reported nintedanib adverse events (AEs) at inclusion. At 12 months, a non-statistically significant benefit in K-BILD's total score was maintained (p=0.23) (Table 1B). Furthermore, most patients that completed the iPSP (92%) showed stabilization or improvement of their total K-BILD score. The EQ-5D-5L and SGRQ-I scores were similar between baseline, months 6 and 12 (Table 1B). According to the HRDS, low mood or depression was reported at baseline by almost 25% of patients. A significant improvement in the emotional state was found at month 6 (p<0.001), but not at month 12 (Table 1B).

Values of the QoL assessment (primary objective) and secondary objectives at 6 and 12 months.

| N=97 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | p value | 12 months | p value | |

| Primary objective: QoL | |||||

| K-BILD; mean (SD) | n=97 | n=92 | n=85 | ||

| Dyspnea/activities | 57.3 (27.4) | 64.2 (26.4) | 0.002 | 61.5 (27.5) | 0.080 |

| Psychological | 71.7 (22.2) | 75.1 (20.9) | 0.120 | 73.8 (21.7) | 0.314 |

| Chest symptoms | 77.4 (19.4) | 78.2 (16.8) | 0.620 | 77.2 (17.9) | 0.220 |

| TOTAL | 70.1 (19.4) | 73.8 (18.3) | 0.050 | 72.3 (19.4) | 0.230 |

| SGRQ-I; mean (SD) | n=97 | n=92 | n=85 | ||

| Symptoms | 50 (22.6) | 46.3 (24.4) | 0.099 | 49.0 (22.4) | 0.501 |

| Activities | 47.7 (28.3) | 46.3 (27.8) | 0.449 | 49.6 (30.2) | 0.182 |

| Impacts | 24.4 (21.2) | 22.8 (19.2) | 0.212 | 24.2 (21.1) | 0.843 |

| TOTAL | 35.4 (21.0) | 33.5 (19.7) | 0.130 | 35.6 (21.5) | 0.346 |

| EQ-5D-5L; mean (SD) | n=97 | n=92 | n=85 | ||

| EQ-VAS | 71.0 (19.1) | 72.5 (21.1) | 0.224 | 73.3 (16.2) | 0.372 |

| EQ-5D utility index | 0.901 (0.11) | 0.911 (0.11) | 0.061 | 0.919 (0.13) | 0.101 |

| HDRS; n(%) | n=67 | n=67 | n=62 | ||

| No depression | 50 (75) | 55 (82) | 0.000 | 58 (93.5) | 0.125 |

| Subclinical | 13 (19.4) | 10 (10.9) | 3 (3.6) | ||

| Mild | 4 (6) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| HADS; n(%) | N=97 | N=92 | 0.321 | N=84 | 0.986 |

| Anxiety – Normal | 75(77.3) | 71 (77.2) | 67(79.8) | ||

| Borderline abnormal | 14 (14.4) | 14 (15.2) | 10 (11.9) | ||

| Abnormal | 8 (8.2) | 7 (7.6) | 7 (8.3) | ||

| Depression – Normal | 79 (82.3) | 75(81.5) | 0.940 | 69 (82.1) | 0.986 |

| Borderline abnormal | 9 (9.4) | 10 (10.9) | 7 (8.3) | ||

| Abnormal | 8 (8.3) | 7 (7.8) | 8 (9.5) | ||

| Secondary objectives | |||||

| MIP-MEP; mean (SD) | n=95 | n=87 | n=74 | ||

| MIP | 76.4 (31.2) | 84.8 (31.3) | 0.010 | 85.6 (31.3) | 0.042 |

| MEP | 103.9 (41) | 114.6 (43.4) | 0.052 | 116.0 (48.1) | 0.130 |

| Lung function parameters; mean (SD) | n=91a | n=88 | n=85 | ||

| FVC (ml) | 2340 (1170) | 2730 (830) | – | 2760 (700) | – |

| FVC (%) | 82.9 (20.4) | 82.8 (20.6) | 81.8 (19.0) | ||

| DLCO (%) | 53.5 (15.5) | 48.1 (15.1) | 47.7 (15.2) | ||

| Disease progression; n(%) | n=97b | n=88 | n=85 | ||

| 28 (30.8) | 9 (19.6) | – | 4 (12.1) | – | |

| Hospitalizations; n(%) | n=97b | n=88 | n=85 | ||

| 8 (8.5) | 4 (7.1) | – | 5 (10.6) | ||

| 6MWT mean (SD) | N=73 | N=88 | – | N=81 | – |

| Walk distance, m; | 439 (89.9) | 414.6 (95.6) | 411.4 (104.3) | ||

| Initial SpO2, % | 95.5 (1.9) | 95.0 (3.2) | 95.6 (1.7) | ||

| Final SpO2, % | 88.9 (6.1) | 89.2 (5.9) | 89.6 (5.8) | ||

P value vs. baseline score.

Key: IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; iPSP: IFP patient support program; SD: standard deviation, FVC: forced vital capacity, DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide. NA: not applicable; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; K-BILD: The King's Brief Interstitial Lung Disease questionnaire; m: meters; MIP-MEP: maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures; SD: standard deviation; SGRQ-I: IPF-specific version of St George's Respiratory Questionnaire; SpO2: oxygen saturation.

Secondary objectives. No significant differences in hospitalizations and dyspnea were observed prior to and during the iPSP (Table 1B). Interestingly, respiratory muscle strength (MIP and MEP) was higher at 12 months (p=0.010 and p=0.042) (Table 1B). The 6MST showed a greater number of steps (mean) at 12 months (p<0.001), however no significant change was found in the 6MWT distance (meters) and the nadir oxygen saturation (Table 1B). PFTs at the time of patient recruitment showed FVC% 82.9±20.4 and DLCO% 53.49±15.5. Disease progression was reported in 30.8% of patients during the 12 months prior to inclusion and in 12.1% over the 12 months of the iPSP (Table 1B), which could be due not only to the iPSP but also to the pharmacological treatment initiated in incident cases almost at the same time.

The most frequent AEs at baseline were loss of appetite (30%) and diarrhea that required daily astringent medication (15%). Milk, coffee, and cold drinks were the most frequently eliminated dietary elements for reducing gastrointestinal AEs. At 12 months, loss of appetite was reduced to 18% and diarrhea to 10.6% of cases. During the study, nintedanib was temporarily dose-reduced in 20 patients (20.6%) and withdrawn in 5 patients (5.15%). Five patients died, one due to cancer (pancreas), and four due to disease progression or acute exacerbation. Two patients underwent lung transplant.

Adherence to the iPSP was 88%. Patients’ satisfaction with the iPSP was high (84% very satisfied; 16% satisfied). The utility and benefit of the iPSP were stated by 95.3% of patients, mainly for control/follow-up (27.2%), guidelines/tips/information (19.8%), and accompaniment/psychological support (14.8%).

The integral and multidisciplinary management provided by this homecare iPSP covers several factors that may improve and tailor the approach to IPF independently of patient's residence, enhancing equity to holistic care.12 Our results demonstrate that the homecare iPSP not only benefits IPF patients at 6 months, as previously reported in other PSPs,7,13 but also continues to benefit them at 12 months. Further than achieving the primary objective that was to maintain the QoL measured by K-BILD in IPF patients over 12 months, this iPSP also significantly improved the QoL at 6 months, probably due to the intensity of the initial physiotherapeutic activities and emotional support among other actions personalized by patient's needs.

In concordance with previous clinical and real-world studies, diarrhea was one of the most common AE at baseline (15%) and 12 months (10.6%).17 This percentage was lower than previously reported (ranging from 31.6 to 62.9%)17 as well as drug withdrawal.18 The different reported prevalence of diarrhea associated to nintedanib could be due to differences in the methodology (poorer systematic adverse event reports in prospective studies than in clinical trials) and timelines, but also to increased acknowledgment about the nutritional prevention and management of this gastrointestinal side effect. This finding could positively impact patient outcome considering the inhibition of lung function decline reported with antifibrotic treatment in IPF.19

We corroborate the positive impact on the psychological well-being reported by patients according to previous experiences at home, including PSP phone calls13 and home monitoring experience.20

The main study limitation is that this type of program is difficult to implement in all countries. Even in our country, the inclusion of patients was only possible in those regions with nurses and physiotherapists of Esteve-Teijin, a company that delivers patient home service for respiratory therapy (oxygen and non-invasive respiratory devices) through a contract with the healthcare regional system. However, the iPSP was able to cover a region of 8.88 million population providing a multidisciplinary ILD homecare service by the same expert team, independently of the area (rural or urban) and distance to the ILD expert centers, trying to improve IPF treatment equity.9

A homecare integral PSP may maintain or improve QoL over one year in most IPF patients and ensures the optimal management of antifibrotic AEs.

Trial registrationEthics approval and consent to participateThe iPSP was approved by Bellvitge University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (PR118/18) and registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05173571; 30/12/2021).

The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Spanish Organic Law 15/1999 of Protection Personal Data. All patients were informed about the study both verbally and with written information, and any potential concerns about the study were solved by the investigators at each site. Patient informed consent was signed by all subjects before being included in the study.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

FundingGrants and sponsoring: Esteve-Teijin. Esteve-Teijin afforded the personal cost of nurses and physiotherapists as well as the design and monitoring of the iPSP, Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) Spain contributed with the cost of technical home devices used for measuring the different variables. BI had no role in the design, analysis, or interpretation of the results in this study. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to BI substances, as well as intellectual property considerations. BRN-Fundació Ramon Pla Armengol. Proyectos de Programación Conjunta Internacional, ISCIII (AC19/00006) cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Institutional support of the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflict of interestsM. Molina-Molina has received grants or support for scientific advice from Ferrer, Esteve-Teijin, Pfizer, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and Galapagos.