Forest fires seriously affect not only the environment and the economy, but also our health.1 Emissions from forest fires have been associated with a general increase in morbidity and mortality.2–8

Our aim was to analyze the possible effect of forest fires on admissions for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma in Catalonia (Spain).

Figures on the area burned each month during the years of the study were provided by the Department of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries, Food and Environment of the Government of Catalonia. Data provided for each region and month were pooled to compute the total area of forest burned in each healthcare area.

Data on hospital admissions were provided by the Department of Health of the Government of Catalonia, using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) diagnostic coding at discharge. For each health region, we obtained the total number of monthly hospital admissions and the number of admissions for heart failure (codes 428.0, 428.1, 428.20, 428.21, 428.22 and 428.23), acute myocardial infarction (410.01, 410.11, 410.21, 410.31, 410.41, 410.51, 410.61, 410.71, 410.81 and 410.91), chronic bronchitis (491.21 and 491.22), and asthma (493.02, 493.12, 493.21, 493.22, 493.81 and 493.82).

Mean monthly temperature and monthly average wind speed during the study period were obtained from the Catalan meteorological agency station located nearest the capital city of each region (http://www.meteo.cat, consulted 13 February 2016). The mean of the different temperatures in each of the subregions that constitute a healthcare region was calculated.

The relationship between hospital admissions and ambient temperature, relative humidity and the forest area burned was analyzed using quasi-Poisson regressions. The 3 risk factors were initially evaluated separately, and those which reached statistical significance were subsequently entered in a simple multiple regression.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital.

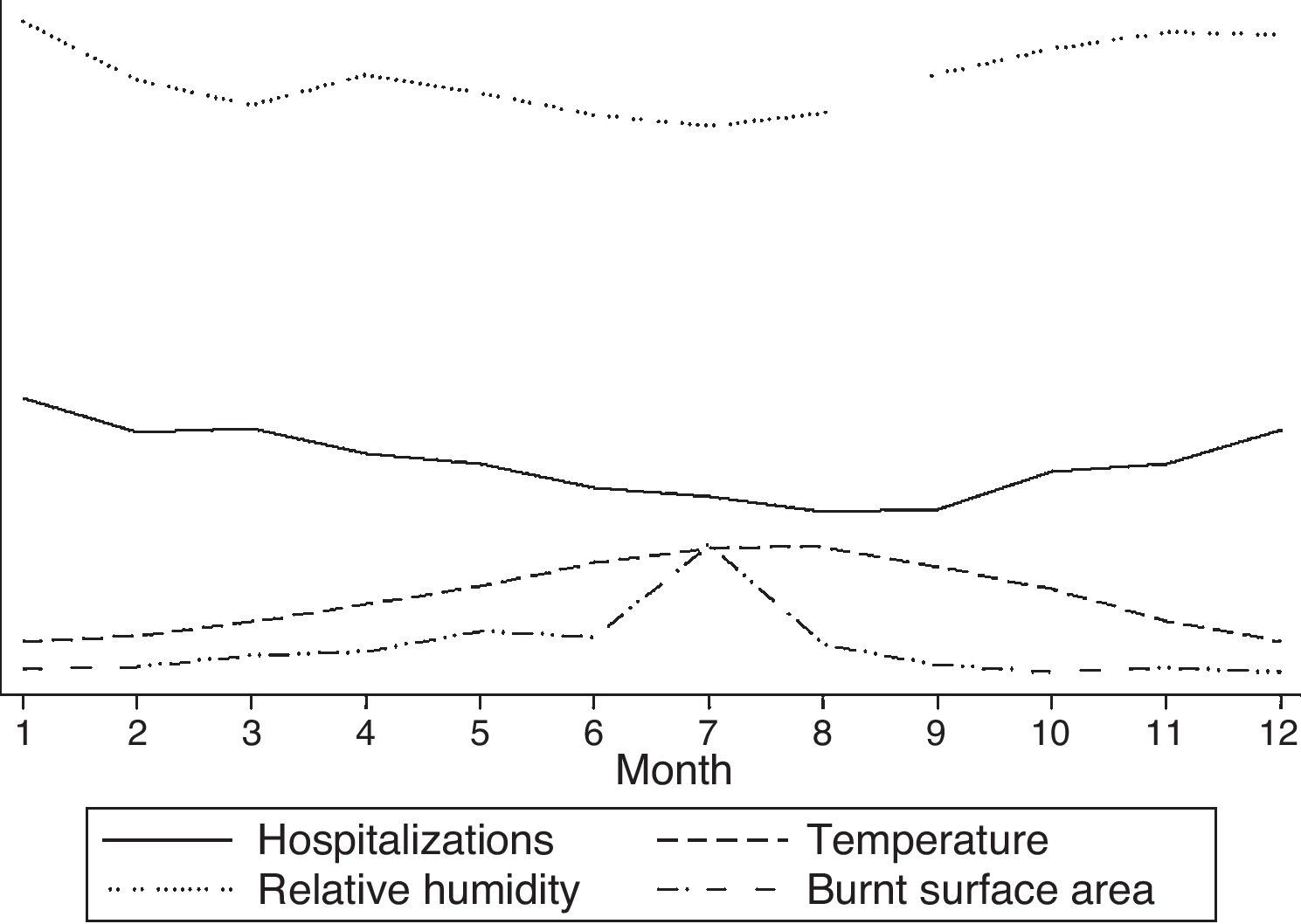

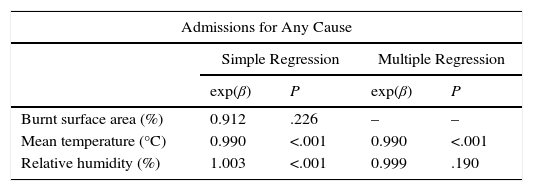

Results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. An increase in all-cause hospital admissions when temperatures dropped and relative humidity increased was observed in the simple regression procedure. In the multiple regression, only temperature maintained statistical significance (P<.001). In the case of acute myocardial infarction, the number of hospital admissions was significantly associated with low temperature (P<.001). The number of admissions for heart failure was associated in the multiple regression with low temperature (P<.001) and with relative humidity (P<.001). All variables in the simple regression were significantly associated with the number of admissions for chronic bronchitis, including the percentage of burned forest surface area (P=.023). However, in the multiple regression, only low temperature (P<.001) and relative humidity (P=.004) remained statistically significant. Burned surface area was significantly associated with the number of hospitalizations for asthma when analyzed separately (P=.009). In the multiple regression, only low temperature was significantly associated with the number of hospital admissions (P<.001). No differences were found when the data were analyzed using information from whole years or only from the months with more fires.

Association Between Hospitalizations and Environmental Factors.

| Admissions for Any Cause | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression | |||

| exp(β) | P | exp(β) | P | |

| Burnt surface area (%) | 0.912 | .226 | – | – |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 0.990 | <.001 | 0.990 | <.001 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 1.003 | <.001 | 0.999 | .190 |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression | |||

| exp(β) | P | exp(β) | P | |

| Burnt surface area (%) | 0.862 | .150 | – | – |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 0.987 | <.001 | 0.987 | <.001 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 1.004 | <.001 | 0.999 | .255 |

| Heart Failure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression | |||

| exp(β) | P | exp(β) | P | |

| Burnt surface area (%) | 0.740 | .100 | – | – |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 0.974 | <.001 | 0.973 | <.001 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 1.006 | <.001 | 0.995 | <.001 |

| Chronic Bronchitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression | |||

| exp(β) | P | exp(β) | P | |

| Burnt surface area (%) | 0.270 | .023 | 0.686 | .281 |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 0.956 | <.001 | 0.955 | <.001 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 1.011 | .001 | 0.992 | .004 |

| Bronchial Asthma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression | |||

| exp(β) | P | exp(β) | P | |

| Burnt surface area (%) | 0.145 | .009 | 0.779 | .487 |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 0.947 | <.001 | 0.948 | <.001 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 1.022 | <.001 | 1.001 | .826 |

Our study reveals a significant association between a drop in ambient temperature and an increase in hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic bronchitis, and bronchial asthma. However, we were unable to detect a significant association between the burned forest area and hospital admissions for these diseases.

The relationship between fires and respiratory disease exacerbations has been described previously. In 1987, Duclos et al. reported an increase in the number of emergency visits for asthma and COPD.2 Subsequently, Mott et al. found an increase in the rate of urgent consultations for respiratory disease during a forest fire in California, compared to data from the previous year.3 Exposure to environmental smoke has been associated with the appearance of both respiratory and non-respiratory symptoms.4 Caamano-Isorna et al. reported an increase in the need for medication for obstructive respiratory disease in men living in areas affected by a wave of forest fires in Galicia (Spain).6 Emmanuel7 reported an increase in PM10 levels associated with an increase in upper airway diseases, asthma, and rhinitis, with no evidence of an increase in hospital admissions or mortality. Haikerwal et al.8 described an increased risk of attending the emergency department due to asthma during a period of fires associated with increased concentrations of PM2.5 particulates.

In our study, we found a negative relationship between ambient temperature and the different diseases, an association that has been described previously. In the case of COPD, a fall in temperature is associated with a decline in lung function9 and an increase in the frequency of exacerbations.9–12 With regard to bronchial asthma, an increase in hospitalizations coinciding with an increase in temperature in the hottest months of the year and a decrease during the cold season have been described.13,14 An increase in respiratory symptoms, particularly among asthma patients with poorer control, has also been reported.15

This study highlights the association between a fall in ambient temperature and admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory disease; however, we were unable to relate the extent of burnt forest with hospitalizations. The main strengths of this work lie primarily in the long study period analyzed. Secondly, the data were retrieved from all hospitals in the public network of an autonomous community.

Our study has several limitations. With regard to exposure, we were unable to factor in changes in the concentrations of the different pollutants or their duration. This would have provided information on the intensity of such exposure and contributed to a better evaluation of the possible adverse effects of forest fires on people's health. We were also unable to determine levels of exposure as a function of the distance between the area of residence and the source of the fire, and we have analyzed all the inhabitants of the region on an equal basis. Another possible limitation is the fact that we analyzed the effect (i.e., hospitalizations) on the basis of the diagnostic code at discharge (ICD-9), which is a potentially unreliable method.

Please cite this article as: Garcia-Olivé I, Radua J, Salvador R, Marin A. Asociación entre incendios forestales, temperatura ambiental e ingresos cardiorrespiratorios entre 2005 y 2014. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:525–527.