Gas embolism is a rare but potentially fatal complication that occurs as a result of air entering the venous or arterial vascular system. Causes include surgery, trauma, vascular interventionism, and barotrauma.1 We report the case of an adult male undergoing computed tomography (CT)-guided transthoracic core needle biopsy (CNB) of a solitary pulmonary nodule, who developed a complication of arterial gas embolism.

This was is a 57-year-old man, active smoker and habitual drinker of alcohol, with a history of liver disease and colorectal carcinoma of the cecum, treated laparoscopically with an extended right hemicolectomy in 2013. Four years later, a follow-up examination revealed a suspected peritoneal nodule corresponding to a tumor implant. A solitary pulmonary nodule was also observed in the lingula, measuring 17×24mm in diameter, hypermetabolic on PET–CT (maximum SUV 3.4), and as such, suggestive of malignancy. For that reason, we decided to perform a CT-guided CNB. At the time of admission, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable, with an oxygen saturation of 98% baseline and normal cardiopulmonary auscultation.

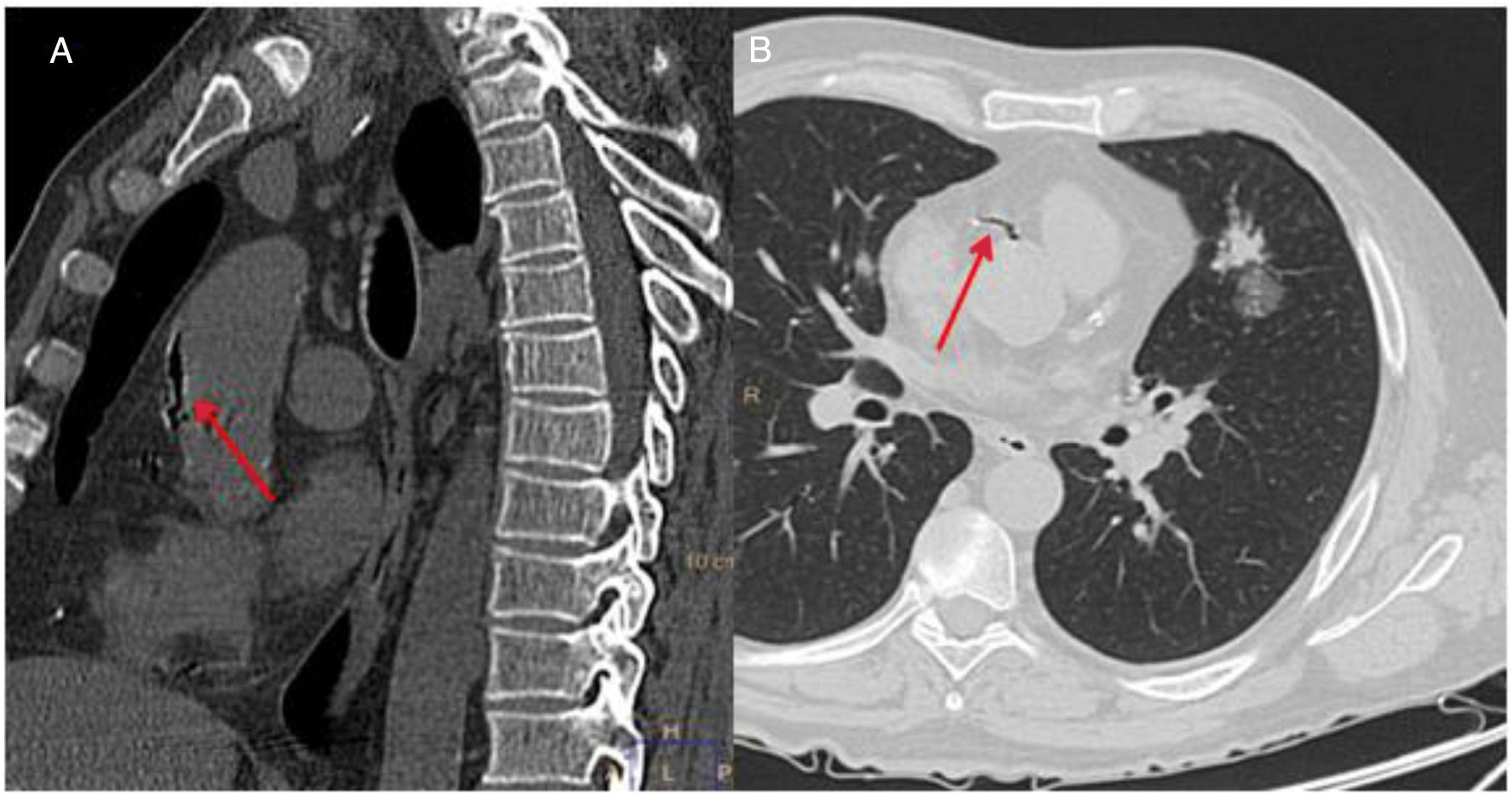

A follow-up chest CT was performed after the CNB, In that examination, a small left pneumothorax and local perinodular hemorrhage were observed, along with a small amount of air in the ascending thoracic aorta and the right coronary artery (Fig. 1). The patient then experienced a sudden decrease in his level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale 5/15), with arterial hypotension (BP 80/40mmHg), bradycardia (HR 35bpm), and marked desaturation (oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry less than 50%), requiring orotracheal intubation and connection to mechanical ventilation. An electrocardiogram was subsequently performed that showed alterations consistent with complete atrioventricular block and acute coronary syndrome, with anterior ST segment elevation. Given these findings, atropine and an infusion of norepinephrine were administered, with subsequent recovery of heart rate and BP. In view of the possibility of a concomitant cerebral embolism, given the neurological symptoms described, we also performed a head CT scan, which showed no acute intracranial alterations, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring and follow-up.

During his stay in the ICU, the patient remained under sedation and analgesia with remifentanil infusion. He developed a series of seizures that resolved with midazolam. Once the patient was hemodynamically stable, noradrenaline was withdrawn and normalization of the electrocardiographic changes was confirmed, with no changes detected in a transthoracic echocardiogram. In respiratory terms, the patient improved rapidly and could be promptly extubated. He was later transferred to the respiratory medicine ward, where he remained in a stable clinical and hemodynamic situation and was subsequently discharged.

The pathologic study of the CNB revealed pulmonary parenchyma infiltrated by a neoplastic proliferation of epithelial lineage and glandular growth, lined by pseudostratified columnar cells, which showed enlarged, irregular, markedly pleomorphic nuclei, with occasional mitotic figures. These data guided diagnosis of a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, while the immunohistochemical study was consistent with a colorectal etiology (CK20/CdX2-positive, CK7/TTF-1 negative).

Arterial gas embolism is an extremely rare but potentially fatal complication in image-guided procedures for obtaining lung biopsies. It is caused by the entry of ambient air into the pulmonary veins, which then circulates to the atrium and left ventricle, and subsequently to the arterial circulation.2 The risk of arterial gas embolism is increased by coughing fits or tachypnea. Pneumothorax and pulmonary parenchymal hemorrhage are the most common complications of CNB. Gas embolism is much less frequent, with an incidence ranging between 0.02% and 0.07%.3,4

The symptoms of gas embolism vary depending on the organ involved. The main one is the brain and, as a result, the patient may develop an altered level of consciousness or neurologic deficit. Another possible manifestation is acute myocardial infarction. The skin and retinal arteries can also be affected.2–6

A definitive diagnosis is obtained by the demonstration of air in the intravascular arterial space of the affected organs in patients with risk factors for arterial gas embolism. It should be noted that air is quickly reabsorbed from the circulation, so sometimes it is not possible to demonstrate its presence. In these cases, a suspected diagnosis must be made if consistent symptoms develop in a congruent risk situation.2–6

When a diagnosis of gas embolism is suspected or confirmed, it is important to act quickly. The patient must be placed in a supine or Trendelenburg position,7 avoiding right lateral decubitus. Respiratory and hemodynamic stability must be ensured with high-flow oxygen therapy or hyperbaric chamber, mechanical ventilation, volume expanders, ionotropic drugs, and advanced cardiac life support.

To minimize the risk, the patient should be immobilized and instructed during the procedure to breathe superficially and to avoid talking or coughing; in certain guidelines, it is recommended that the procedure be performed with a degree of conscious sedation, and that radiological planning should be made prior to the procedure, confirming the presence of the needle in the lesion before the biopsy.2

With regard to prognosis, various series have reported a mortality rate of between 12% and 30%, depending on whether the gas embolism is venous or arterial, severity and mortality being greater in the latter case. We must remember that, even though systemic embolism may be asymptomatic, only 2ml of air in the cerebral circulation or 1ml in the pulmonary venous circulation can have fatal consequences.5

Please cite this article as: Oliva Ramos A, de Miguel Díez J, Puente Maestu L, de la Torre Fernández J. Embolia gaseosa arterial: una rara complicación de la biopsia con aguja gruesa en el diagnóstico del nódulo pulmonar solitario. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:492–493.