Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive histologic type of lung cancer, and accounts for approximately 10%–15% of all cases. Few studies have analyzed the effect of residential radon. Our aim is to determine the risk factors of SCLC.

MethodsWe designed a multicenter, hospital-based case-control study with the participation of 11 hospitals in 4 autonomous communities.

ResultsResults of the first 113 cases have been analyzed, 63 of which included residential radon measurements. Median age at diagnosis was 63 years; 11% of cases were younger than 50 years of age; 22% were women; 57% had extended disease; and 95% were smokers or former smokers. Median residential radon concentration was 128Bq/m3. Concentrations higher than 400Bq/m3 were found in 8% of cases. The only remarkable difference by gender was the percentage of never smokers, which was higher in women compared to men (P<.001). Radon concentration was higher in patients with stage IV disease (non-significant difference) and in individuals diagnosed at 63 years of age or older (P=.032).

ConclusionsA high percentage of SCLC cases are diagnosed early and there is a predominance of disseminated disease at diagnosis. Residential radon seems to play an important role on the onset of this disease, with some cases having very high indoor radon concentrations.

El cáncer de pulmón de célula pequeña (CPCP) es el tipo histológico más agresivo de las neoplasias broncopulmonares. Representa en torno al 10-15% de todos los casos. Muy pocos estudios han analizado la influencia del radón residencial. Se pretende conocer los factores de riesgo del CPCP.

MétodosSe diseñó un estudio de casos y controles multicéntrico y de base hospitalaria, con 11 hospitales de 4 comunidades autónomas.

ResultadosSe analizan los primeros 113 casos reclutados y de ellos 63 con resultados de radón residencial. La edad mediana al diagnóstico fue de 63 años y un 11% de los casos eran menores de 50 años. El 22% de los casos eran mujeres. El 57% tenían enfermedad en estadioIV y el 95% eran fumadores o exfumadores. La concentración mediana de radón residencial era de 128Bq/m3. Un 8% de los casos tenían concentraciones superiores a 400Bq/m3. Por sexo, la única diferencia relevante fue en el porcentaje de mujeres nunca fumadoras, más elevado que para los hombres (p<0,001). La concentración de radón fue superior para los sujetos con enfermedad en estadioIV (diferencias no significativas) y fue más elevada en los pacientes diagnosticados con 63 años o más (p=0,032).

ConclusionesExiste un diagnóstico a una edad temprana en buena parte de los casos con CPCP y predomina la enfermedad metastásica al diagnóstico. El radón residencial parece jugar un papel importante en la aparición de la enfermedad, existiendo casos diagnosticados con concentraciones de radón muy elevadas.

Lung cancer is currently a major health problem. According to GLOBOCAN 2012, around 1825000 new cases are reported worldwide each year, with a total of 1590000 annual deaths, making it the leading cause of death in developed countries. In Europe, it accounts for 26.3% of all cancer deaths.1,2 In Spain in 2014, 21251 individuals died of lung cancer, 19.1% of whom were women.3

The risk factors for small cell lung cancer (SCLC), other than smoking,4 have not been studied in depth, since SCLC accounts for around 14% of all cases of lung cancer, and as such is much less common than adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. In Spain, around 20% of lung cancer cases are SCLC.5 Although the incidence of SCLC is on the decline, the incidence in women is on the rise, with a male/female ratio of 1:1.6,7

Of all lung tumors, SCLC carries the worst prognosis. Although the initial response rate in SCLS is high, it is associated with a high rate of mortality because virtually all patients rapidly develop resistance to treatment. The 5-year survival rate of SCLC is 10% in patients with stage I–III, and only 4.6% at 2 years in cases diagnosed in stage IV. In both cases, the survival rate is slightly higher in women than in men (5.94% vs 3.57% in stage IV and 12.25% vs 7.51% in stages I–III).8,9

Of all lung tumors, SCLC is most closely associated with smoking, although there may be other risk factors.10 The frequency of this entity is relatively low, so these risk factors have not been studied in depth, and may include residential radon,11,12 diet,10–15 occupation,16 and certain leisure activities.17

For this reason, there is a need for multicenter studies to better characterize the etiology of this disease. When biological samples are obtained in the context of such studies, they will help identify genes or polymorphisms that might influence both the etiology of the disease and response to treatment.

The aim of this article is to report the start of the SMALL CELL study, describe its methodology, and communicate the characteristics of the first 113 patients recruited. This study is being conducted in an area with a high concentration of radon gas and is intended to serve as an international reference for determining in depth the causes of SCLC and the role of residential radon in this disease.

Subjects and MethodsDesign and ScopeThe SMALL CELL study is a hospital-based, multicenter, case-control study conducted in 11 Spanish hospitals in 4 autonomous communities and 1 Portuguese hospital: Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro de Vigo, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, Centro Oncológico de Galicia, Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti de Lugo, Complejo Hospitalario Arquitecto Marcide de Ferrol, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León, Complejo Asistencial de Ávila, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro and Centro Hospitalar do Porto.

Patients presenting with a histopathological diagnosis of SCLC are being recruited; controls will be patients undergoing non-complex surgery not related to tobacco use. Both cases and controls are over 25 years of age with no history of cancer. The same information will be collected from all study participants (both cases and controls). The study protocol was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of the Health Area of Santiago de Compostela with reference number 2015/222. STROBE guidelines for reporting results from observational studies have been used as far as possible in the conduct of this study.18

Data CollectionResearchers at each center selected cases with SCLC. Each participant completed a questionnaire during a personal interview to ascertain their demographic data, place of residence, family history and previous lung diseases, biomass combustion in the home, work and leisure activities (DIY, artistic painting, varnishing, modeling), as well as tobacco consumption (type, quantity) and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, alcohol consumption, and dietary habits.

Biological SamplesThree ml of whole blood was drawn from each participant to be used after completion of recruitment to determine complete deletion of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes, polymorphism in the XRCC1 gene (Arg399Gln), polymorphism in the OGG1 gene (Ser326Cys), polymorphism in the ERCC1 gene (C8092A), 2 polymorphisms in the ERCC2 gene (Asp312Asn and Lys751Gln),19 alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and the presence of human papilloma virus.20 These genes will be analyzed in order to determine whether their presence or polymorphisms are associated with a greater or lesser likelihood of developing SCLC.

Determination of Residential RadonAll study subjects were given a radon detector and instructions on how to install it. The radon detector is placed in the main bedroom for at least 3 months, away from doors, windows and electricity sources. All participants receive 2 follow-up phone calls, the first to ensure they have installed the detector correctly, and the second to remind them to return it after at least 3 months. The detectors are then sent to the coordinating center. Once received, they are read in the Galicia Radon Laboratory. The measurement system uses a calculation algorithm adjusting for season and duration of the exposure period, among other factors. The Galicia Radon Laboratory has participated in intercomparison exercises that indicate that the quality of their determinations is excellent.21,22

Statistical AnalysisA univariate and bivariate analysis has been conducted of the first cases included in the study. Subanalyses were conducted for sex and disease stage at diagnosis (limited or extensive disease). Order-based measures have been used instead of measures of central tendency to describe residential radon concentrations, as the distribution of radon is log-normal. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v22.

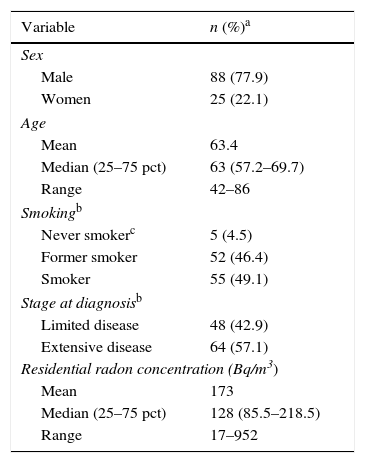

ResultsBy October 25, 2016 we had recruited113 patients, of whom 22.1% were women (25). The median age at diagnosis was 63 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 57–70 years, and 11.5% of the cases were under the age of 50. In total, 42.9% (48 cases) had limited disease at diagnosis (stages I–III); 4.5% were never smokers and 49.1% were smokers at the time of diagnosis. The return rate for detectors was 79.8%, and residential radon was measured in 63 cases. Median radon concentration was 128Bq/m,3 and 25% of the cases showed concentrations above 223Bq/m3 in the home at the time of diagnosis. Concentrations higher than 400Bq/m3 were detected in 7.9% of the cases. Cases who were never smokers had a median concentration of residential radon of 233Bq/m.3 Only 1 of the 5 never smokers had been exposed to tobacco smoke at home. Median cumulative consumption of tobacco among smokers and former smokers was 48 pack-years. Median duration of abstinence in former smokers was 5.5 years, and 25% of the former smokers had been abstinent for more than 19 years. A detailed description of the study subjects is listed in Table 1.

Description of the Study Subjects.

| Variable | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 88 (77.9) |

| Women | 25 (22.1) |

| Age | |

| Mean | 63.4 |

| Median (25–75 pct) | 63 (57.2–69.7) |

| Range | 42–86 |

| Smokingb | |

| Never smokerc | 5 (4.5) |

| Former smoker | 52 (46.4) |

| Smoker | 55 (49.1) |

| Stage at diagnosisb | |

| Limited disease | 48 (42.9) |

| Extensive disease | 64 (57.1) |

| Residential radon concentration (Bq/m3) | |

| Mean | 173 |

| Median (25–75 pct) | 128 (85.5–218.5) |

| Range | 17–952 |

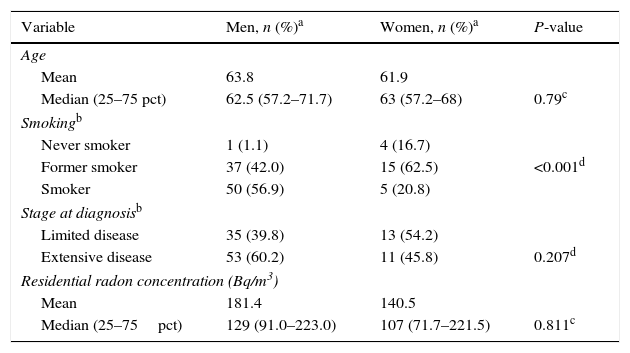

The distribution of the different characteristics of SCLC by sex are shown in Table 2. Women had a median age of 63 years, with an interquartile range of 57–68 years; 54.2% had limited disease and the median radon concentration was 107Bq/m,3 with an interquartile range of 72–221Bq/m.3 In total, 16.7% of the women had never smoked, and 20.8% were smokers at the time of diagnosis. The median age of men at diagnosis was 63 years, with an interquartile range of 57–72 years; 39.8% had limited disease (stages I–III). In total, 1.1% of the men had never smoked, and 56.8% were smokers at the time of diagnosis. Median radon concentration was 129Bq/m,3 with an interquartile range of 91–223Bq/m.3 There were no differences between sexes for any of the above variables, except for tobacco consumption at the time of diagnosis (P<0.001).

Differences in Characteristics of Cases by Sex.

| Variable | Men, n (%)a | Women, n (%)a | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean | 63.8 | 61.9 | |

| Median (25–75 pct) | 62.5 (57.2–71.7) | 63 (57.2–68) | 0.79c |

| Smokingb | |||

| Never smoker | 1 (1.1) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Former smoker | 37 (42.0) | 15 (62.5) | <0.001d |

| Smoker | 50 (56.9) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Stage at diagnosisb | |||

| Limited disease | 35 (39.8) | 13 (54.2) | |

| Extensive disease | 53 (60.2) | 11 (45.8) | 0.207d |

| Residential radon concentration (Bq/m3) | |||

| Mean | 181.4 | 140.5 | |

| Median (25–75pct) | 129 (91.0–223.0) | 107 (71.7–221.5) | 0.811c |

With regard to the consumption of tobacco and disease stages (stages I–III vs stage IV), never-smokers and smokers more frequently presented disseminated disease at diagnosis. Specifically, 39.6% of the subjects with stage I–III disease were smokers at the time of diagnosis, while 55.6% of the subjects with stage IV disease were smokers at diagnosis.

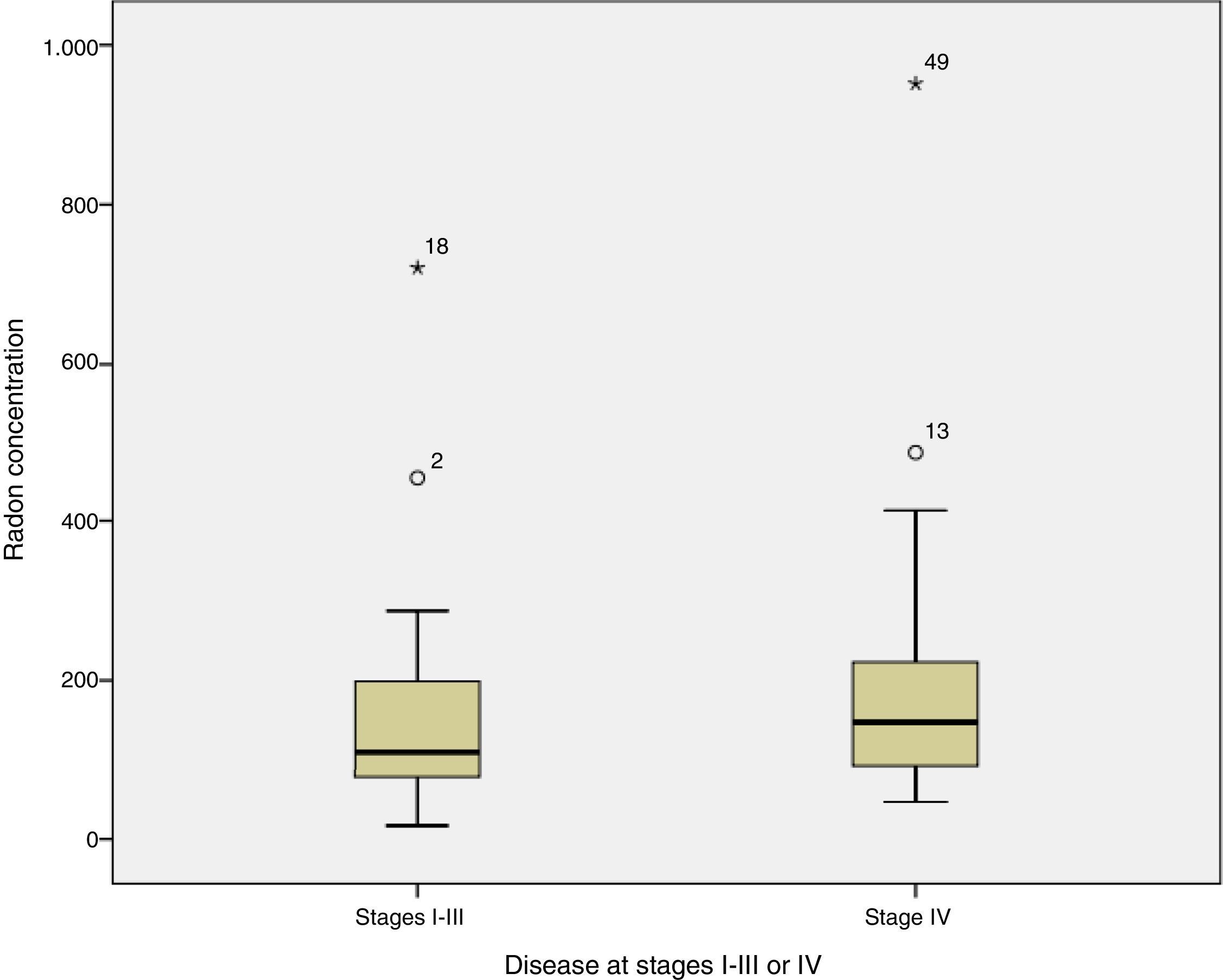

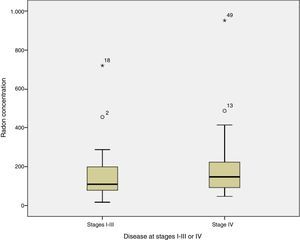

When radon concentrations were compared with disease stage at diagnosis, we found that the median indoor radon concentration in cases diagnosed with disease limited to stages I–III was 109Bq/m,3 compared to 148Bq/m3 in patients diagnosed with stage IV disease (test for median comparison P=0.254). Fig. 1 shows radon concentrations by stage at diagnosis.

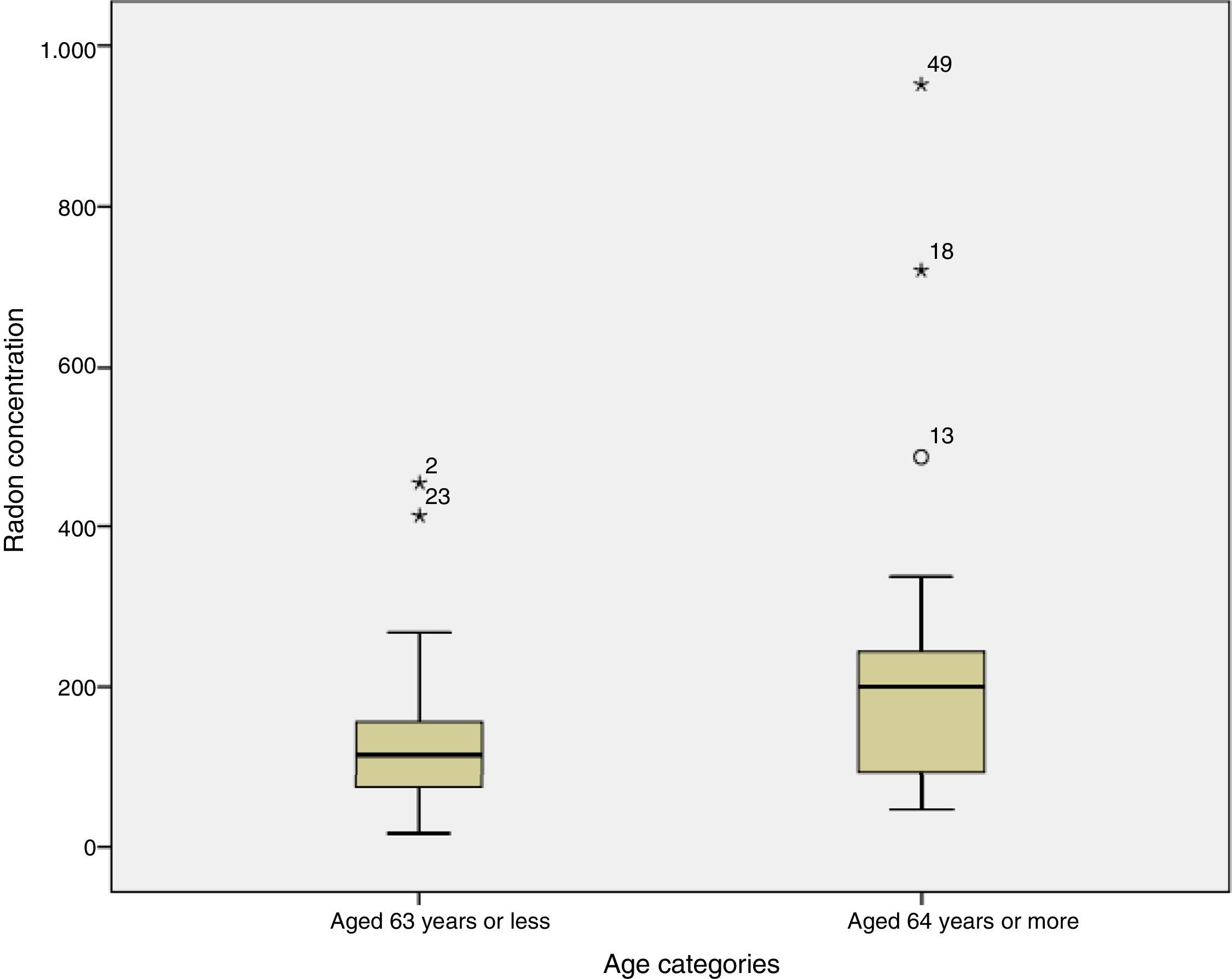

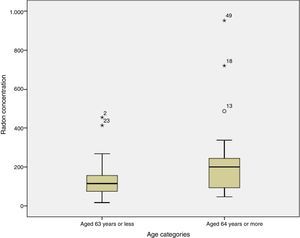

Finally, when the radon concentration was compared to age at diagnosis, we found that subjects aged 63 years or younger had residential radon concentrations of 116Bq/m,3 compared to levels of 200Bq/m3 among subjects diagnosed at 64 years or more; this difference was statistically significant (P=0.032). Fig. 2 shows radon distribution by age at diagnosis, demonstrating that the older subjects seem to have higher concentrations of radon.

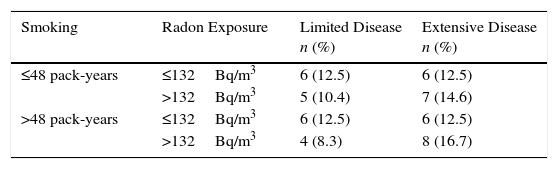

Table 3 shows the distribution of indoor radon and tobacco consumption, simultaneously, by disease stage at diagnosis among smokers. Although only 48 participants presented complete radon and pack-year data, it is clear that the highest percentage of subjects with extensive disease (16.7%) occurs among participants with higher radon exposure and tobacco consumption.

Limited or Extensive Small Cell Lung Cancer by Smoking and Exposure to Residential Radon (n=48).

| Smoking | Radon Exposure | Limited Disease n (%) | Extensive Disease n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤48 pack-years | ≤132Bq/m3 | 6 (12.5) | 6 (12.5) |

| >132Bq/m3 | 5 (10.4) | 7 (14.6) | |

| >48 pack-years | ≤132Bq/m3 | 6 (12.5) | 6 (12.5) |

| >132Bq/m3 | 4 (8.3) | 8 (16.7) |

Only smokers included. Tobacco use and radon exposure classified according to the median.

To our knowledge, the SMALL CELL study is the first to directly analyze risk factors for SCLC exclusively, paying particular attention to exposure to residential radon. The preliminary results from the subjects included to date highlight several factors. Firstly, the earlier age at diagnosis of SCLC compared to NSCLC (63 years vs 70 years) is of interest.7 The percentage of SCLC cases diagnosed at stage IV, around 57%, is similar to that of NSCLC cases diagnosed at stage IV, according to data from North America.23 Age and stage at diagnosis are similar in men and women, although men tend to be diagnosed more often with stage IVcancers. Radon concentration is high in small cell cancers, if compared with data from the general population of Galicia, for example. Individuals with extensive disease have slightly higher radon concentrations, and individuals who are older at diagnosis have significantly higher radon concentrations than younger patients.

Median age at diagnosis of the cases included was 63 years. This is somewhat less than the median age at diagnosis of non-small cell cancers (70 years), and it is striking that more than 11% of cases are diagnosed before the age of 50. This earlier diagnosis can probably be explained by the shorter induction period in SCLC patients compared to NSCLC patients, due to their more intensive use of tobacco.24

The age at diagnosis is very similar in men and women, but a greater percentage of men (around 15%) than women were diagnosed with stage IV disease. This could be because more men than women are smokers and former smokers, and because smokers may have an increased probability of presenting with metastatic disease at diagnosis. A high percentage of women diagnosed − 17% − are never smokers. Previous studies in the same region have shown that SCLC in never smokers is a relatively common cancer in Galicia, and that radon might play a role in its appearance.25

Smoking is clearly the most important risk factor for SCLC. Nearly all (95.5%) of our cases are smokers or former smokers, and tobacco use is more prevalent in men than in women. Never smokers with SCLC are more often women than men, and the histological type most frequently associated with tobacco use is SCLC; both these observations have also been reported elsewhere in the literature.26 We have also found that patients who were smokers at diagnosis have a higher percentage of extensive disease than former smokers, pointing to a possible relationship between intensity of the habit and disease extension at diagnosis. The results also appear to indicate that a higher percentage of subjects with a radon concentration above the median and greater tobacco use are diagnosed with extensive disease, indicating that both risk factors possibly impact on the diagnosis of advanced disease.

Our findings on radon concentration and its possible influence on SCLC are very interesting. Firstly, the radon concentration observed in the SCLC cases (128Bq/m3) exceeds the radon concentration observed in the general population in Galicia (99Bq/m3),27 suggesting that residential radon is a risk factor for SCLC. According to the WHO, the action level of radon is 100Bq/m3.28 The concentration observed in this study is much lower than that detected in a study of never smokers with lung cancer (237Bq/m3).29 This is probably because a much higher concentration of radon is needed to cause lung cancer in never smokers,30 and mainly smokers and never smokers with SCLC were included in this study. Indeed, the median radon concentration in never smokers included in this study is 233Bq/m3, which supports the above statement. The largest study of lung cancer and residential radon published to date31 suggests that SCLC is the type most closely associated with indoor radon. Other research conducted in our region also points to a closer causal association between radon and SCLC and other less common histological types.11 Other studies analyzing environmental pollution and its effect on lung cancer have found that SCLC is also the histological type that carries the greatest risk.32

With regard to the relationship between radon concentration and disease extension at diagnosis, cases with stage IV disease appear to have a somewhat higher residential radon exposure than those diagnosed with stage I–III, although the difference is not statistically significant, and no conclusions can be drawn in this regard. It has been observed that cases diagnosed at older ages are exposed to significantly higher radon concentrations than cases diagnosed at younger ages.

Few published studies address the molecular mechanism by which residential radon can cause lung cancer, and we are even further from explaining its influence on the development of SCLC. It has been speculated that radon could play a part in the appearance of mutations in the p5333 and K-Ras34 genes or even mutations in lung cancer genes, such as EGFR or ALK.35 More research is needed at the molecular level to shed light on this association.

Our study has some limitations. One of these is its sample size; however, these results are preliminary and the study is still recruiting patients. Nevertheless, it is one of the Spanish studies with the greatest number of cases of SCLC. Another limitation is that biological data on susceptible genes are not currently available, and measurements of residential radon have been obtained from only 63 homes. This is because the detectors must be installed in the home for at least 3 months, and the results are then processed in a laboratory. The return rate of detectors is very high (90%), and it must be borne in mind that many patients had already died by the time the detector was sent to the Galicia Radon Laboratory.

This study also has significant strengths. One of these is its multicenter design, which allows for a larger study population and greater external validity. The study was performed primarily in an area where exposure to indoor radon is high, and the greater variability in exposure allows its effect to be more easily studied. Finally, our population consists of individuals who have resided in the same home for long periods of time and have moved little, helping us to explore the causal attribution of radon to SCLC.30

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that the onset of SCLC occurs at an earlier age than NSCLC, and that a significant number of cases are diagnosed before the age of 50 years. Over half of the cases in this series had extensive disease at diagnosis, suggesting an adverse prognosis for many of these patients. Radon appears to affect the development of this histological type of lung cancer, and individuals diagnosed at older ages have higher radon concentrations in the home. Indeed, a significant percentage of cases have very high levels of residential radon. It is essential, then, to support further research on the risk factors for small cell lung cancer and to establish policies for the prevention of exposure to residential radon, without letting up in the fight against smoking.

FundingInstituto Carlos III. PI15/01211. “Small cell lung cancer, risk factors and genetic susceptibility. A multicenter case-control study in Spain (Small Cell Study)”.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Martínez Á, Ruano-Ravina A, Torres-Durán M, Vidal-García I, Leiro-Fernández V, Hernández-Hernández J, et al. Cáncer de pulmón microcítico. Metodología y resultados preliminares del estudio SMALL CELL. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:675–681.

This article is part of the doctoral thesis of Ángeles Rodríguez Martínez.