According to the World Health Organization (WHO), with 10.6 million patients and over 1.5 million deaths estimated to occur in 2021, tuberculosis (TB) is still a global public health priority.1

The COVID-19 pandemic, while stressing health services and delaying TB diagnosis, has contributed to increase the TB patients’ mortality.2–11

The WHO has launched effective strategies to tackle TB1 since 1995 with the launch of the DOTS (Directly Observed Therapy, Short-Course) Strategy, which focused on rapid diagnosis and effective treatment of infectious patients, followed by the Stop TB Strategy in 2026 (which included new challenges such as multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB, HIV co-infection and the role of the private sector among others) and the End TB Strategy in 2014 (going beyond diagnosis and treatment to focus on prevention and the socio-economic interventions necessary to counteract the social determinants of the disease).

As for other global epidemics (HIV/AIDS and Malaria), the concept of eliminating TB was refined in programmatic terms in 1990 and in 2014 WHO developed, in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS), a policy document known as the Framework for TB Elimination.1,12,13

These strategies underpinned the aim of reducing TB incidence and mortality, for which ambitious targets have been established up to the level to consider TB Elimination.1

Recent attention has been brought to TB Elimination considering the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB services.4–11,14

What is TB Elimination?TB Elimination was initially defined by experts from Europe, North America and Japan,15 meeting at the first Wolfheze conference in 1990, as less than one smear-positive case per million population as to ensure that TB will be “no longer a public health threat”.16

In the 2014 WHO framework document, the definition was slightly modified to “fewer than one annual case per million population”, given the perceived relevance of considering all forms of TB, regardless of their bacteriological status.12,17 The concept of TB pre-Elimination was also introduced, defined as 10 cases per million population per year, as a more easily accessible target on the way towards Elimination.17

What TB Elimination is notTB Elimination is not eradication, e.g., “the reduction to zero of the incidence of a particular disease in a defined geographical area as a result of deliberate efforts”18 as TB, characterized by the large reservoir of TB infection,19 cannot in fact be eradicated as other diseases (for example poliomyelitis).

As mentioned above Elimination means to reduce to a very low level the incidence of TB and keep it low, as to prevent any further rise.

TB Elimination is not Ending TB, e.g., meeting the 2035 targets of the End TB Strategy by reducing TB incidence of 90%, TB mortality by 95% (in comparison with 2015 values) and eliminating the “catastrophic costs” for patients.1 Although for a low TB incidence country (e.g., with an incidence below 10 cases per 100,000 population or 100 cases per million) Ending TB means to reach the pre-Elimination threshold, for the majority of the other countries the End TB Targets represent an important reduction of incidence and mortality, whose value depends on the initial TB incidence level of the country considered.

Is TB Elimination for all Countries?According to the WHO framework and because of the important focus on Area 4 (managing TB infection), TB Elimination was seen in 2014 as a strategic approach for countries at low incidence of TB (as said at the level of 100 cases per million population) or around that level.1,20,21

Although some countries define their National Strategic Plans as ‘Elimination Plans’ even being at high incidence, the real approach to TB Elimination is reserved to the low incidence countries, which at the moment are around 60.22

However, a recent Viewpoint published in the European Respiratory Journal1 proposes that all countries can start moving towards TB Elimination by implementing different activities’ packages depending on their epidemiological situation.

What do to Pursue TB Elimination?Eight core areas have been identified in the TB Elimination framework as follows: (Area 1) ensure political commitment, funding, and stewardship for planning and essential services; (Area 2) address the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach groups; (Area 3) address special needs of migrants and cross-border issues; (Area 4) undertake screening and appropriate treatment for TB and TB infection in contacts and selected high-risk groups; (Area 5) optimize the prevention and care of drug-resistant TB; (Area 6) ensure continued surveillance, programme monitoring, and evaluation and case-based data management; (Area 7) invest in research and new tools, and (Area 8) support global TB prevention, care, and control. Although all the eight areas are important, Area 4 is considered pivotal to pursue TB Elimination.15,23

Which New Ideas Have Been Proposed to Involve all Countries in the TB Elimination Track?The recent ERJ viewpoint1 mentioned above classifies countries into 5 stages: 1, High TB incidence (>100 cases per 100,000 population); 2. Moderate TB incidence (30–10 per 100,000); 3. Low TB incidence (10–29 per 100,000); 4. Nearing TB Elimination (1–9 per 100,000); 5. Pre-Elimination countries (<1 case per 100,000 or 10 cases per million).

The countries at higher incidence are supposed to start from implementing or strengthening specific activities and progressively scale-up them while their incidence declines and they advance from stage 1 to stage 5.

Countries in stage 1 should reduce transmission and improve access to care, while improving quality of diagnosis and treatment (e.g., by expanding access to molecular testing and reducing loss to follow-up) in order to reduce their incidence by 50%. Countries in stage 2 should increase the search for undiagnosed cases, focus on risk groups (e.g., prisoners, elderly, etc.), strengthening household contact tracing and treating drug-resistant TB to reduce their incidence by 40%. Countries in stage 3 should tackle outbreaks (using Whole Genome Sequencing) and scale-up Treatment of TB Infection (TPT)24 to be able to potentiate their capacity of tackling Area 4 and reduce TB incidence by 35%. Countries in stage 4 should aim to eliminate in-country TB transmission by ensuring universal contact investigation as well as tackling TB disease and infection in foreign-born migrants in order to reduce their incidence by 30%. Finally, stage 5 countries will be in the position to prevent TB outbreaks and managing all TB infections while keeping quality of, and preparedness for, these interventions as to be able to reduce TB incidence of 25% and proceed to TB Elimination.

Which Best Practices Exist in TB Elimination?The historical studies conducted in Alaska, Northwest Canada and Greenland on the Inuit population from 1952 to 1973 show that an annual incidence reduction of 17% can be achieved tackling TB infection.25

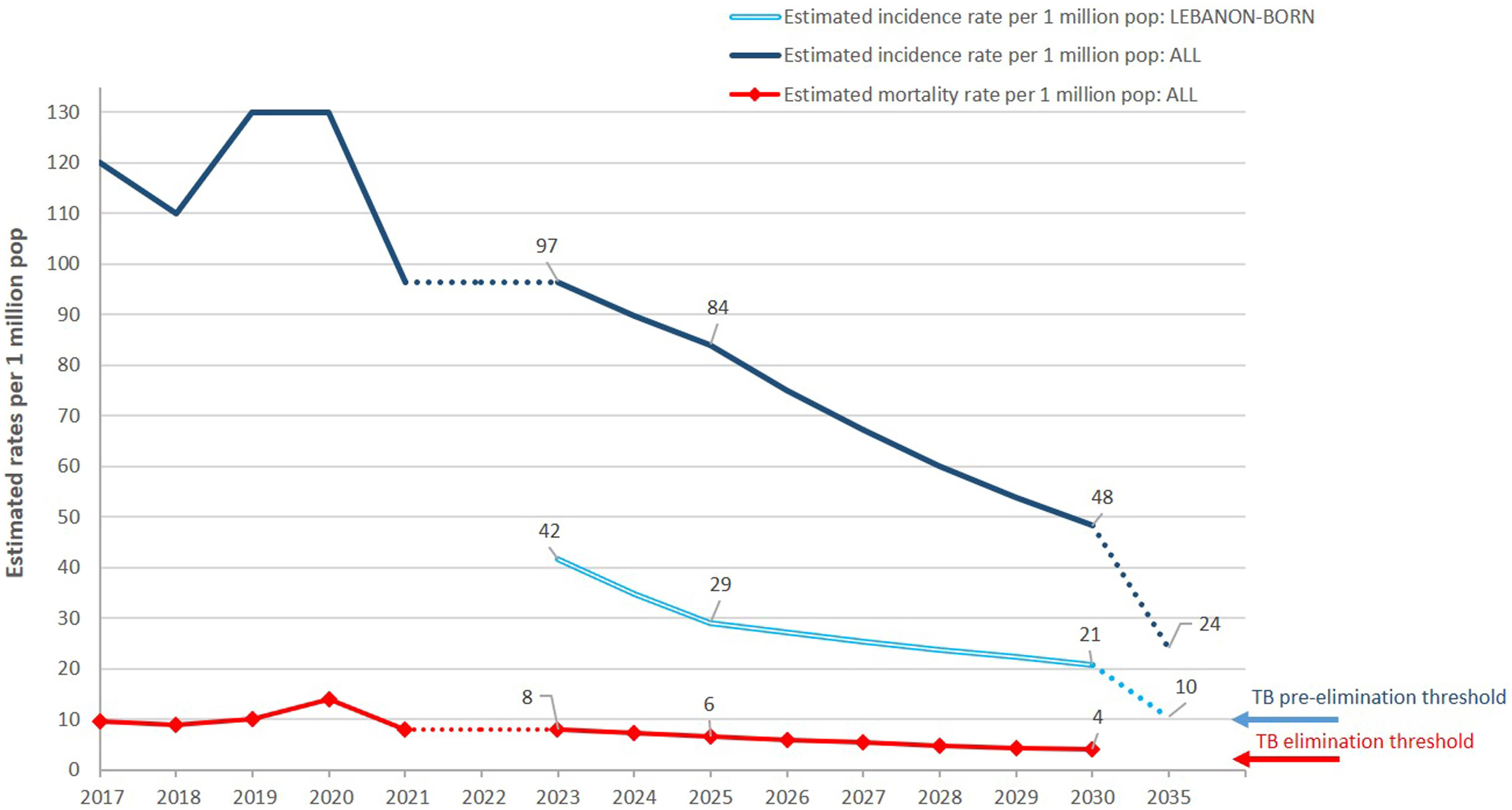

Published experiences exist on the capacity of Cyprus to reach TB Elimination among native-born26 and of Oman to approach the pre-Elimination threshold.27 An interesting approach is that of Lebanon13 (Fig. 1), showing the possibility to reach pre-Elimination among native born and children within the next National Strategic Plan round, as by 2030 the country will reach 20 cases per million in this population. Important reductions of TB incidence have been achieved in Southern Vietnam (19% annual decline, 2104–2018), South Africa (10.3% annual decline, 2015–2021) and New York City (21% decline, 1992–1994), showing the feasibility of what suggested above.28,29 Furthermore, the Marshall Islands achieved, with a single round of testing and treatment, to reduce TB incidence by over 30% in two years, pre-Elimination being feasible by 2025 if repeated rounds of the exercise will continue.30

Trajectory towards pre-Elimination of TB in Lebanon (with permission from Ref. 13). While in the overall population the estimated incidence in 2030 will be 4.8 times higher than the TB pre-Elimination threshold, among Lebanon-born individuals it will be approximately two times higher to reach the threshold by 2035.

It is not easy to predict if TB Elimination will be a feasible global target, given external factors can suddenly humper decades of progress as recently shown by the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the effect of wars and national disasters. However, beyond the capacity to reach a given numeric threshold, the vision of planning activities which can contribute to reduce TB incidence (and mortality) in all countries is important and deserves public health and programmatic attention.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.