Mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes can present in both malignant diseases and benign disorders; therefore, mediastinal biopsy is essential for a definitive diagnosis. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA), a minimally invasive and safe technique, is widely practiced nowadays for mediastinal lesion sampling and staging of lung cancer.1 Nevertheless, intact and larger tissue samples are increasingly needed for pathological, genomic, molecular, and immunological assessments, therefore, the insufficiency of intact biopsy samples acquired by EBUS-TBNA might restrict the diagnostic yield for certain conditions such as lymphoproliferative and granulomatous disorders.2 Transbronchial lung cryobiopsy is a well-known endoscopic procedure employed in the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases.3 Transbronchial mediastinal cryobiopsy (TMC) might be a new clinical approach for the diagnosis of mediastinal lesions. We present a case-series of four consecutive patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA and TMC during the same procedure for diagnostic and staging purposes of mediastinal lesions.

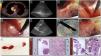

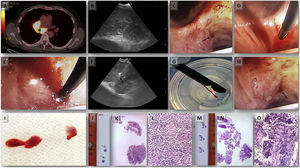

All four patients underwent EBUS-TBNA (EB-1970UK, Linear-Array; Pentax Medical, Tokyo, Japan) under conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl after signing informed consent. The procedure was performed by an interventional pulmonologist with multi-year experience in performing EBUS-TBNA. The clinical characteristics of the patients and the findings at bronchoscopy with both EBUS-TBNA and TMC are shown in Table 1. Rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE) was done on the EBUS-TBNA sample, and cell blocks were prepared from the obtained material. We proceed to describe step by step the complete procedure applying the Ariza-Pallarés method using case 4 of Table 1 as the main example. A 53-year-old male was referred to our Interventional Pulmonology Unit (IPU) in January 2022 to perform a mediastinal biopsy due to suspicion of relapse of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma previously diagnosed in 2016. EBUS-TBNA of station 7 was made at that time without being conclusive; therefore, a mediastinoscopy was performed reaching the final diagnosis. We decided to perform TMC given the relevance of the case. A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan showed an increased FDG uptake at 7 and 11Rs stations (Fig. 1A). After identification of an enlarged station 7 lymph node at EBUS (Fig. 1B), the pulmonologist performed four passes of TBNAs with 22-gauge needle. After initial puncture with the EBUS-TBNA needle, a 1.1mm cryo-probe (Erbecryo 20402-401, Tubingen, Germany) was introduced into the working channel of the EBUS bronchoscope. The cryo-probe was advanced towards the puncture site and inserted gently through the previous puncture site created by the EBUS-TBNA needle (Fig. 1C–E). The EBUS image confirmed the cryo-probe position within the lymph-node (Fig. 1F and supplementary video 1A). The cryo-probe was cooled down for 3s, and then retracted with the bronchoscope and the frozen biopsy tissue attached to the tip of the probe (Fig. 1G). Cryobiopsies were retrieved in saline and fixed in formalin. The cryobiopsy site was immediately examined and no bleeding was observed (Fig. 1H). Three cryobiopsies were obtained (Fig. 1I). In the next pictures we present both the cryobiopsy and the TBNA cell-block samples; the cryobiopsy showed a more compact and complete sample, with a better-preserved architecture and with less artifacts (Fig. 1J–O). Studies have shown potentially limited ability of EBUS-TBNA to diagnose and subtype lymphoma.4 In this case, EBUS-TBNA was positive for lymphoma cells, but mediastinal cryobiopsy allowed a more accurate characterization, which demonstrated a B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of follicular origin, avoiding a possible mediastinoscopy.

Characteristics of the patients who underwent cryobiopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes and findings at cryobiopsy and EBUS-TBNA.

| Patient | Age | Reason for bronchoscopy | Target lymph node for cryobiopsy | Target Lymph node for EBUS-TBNA | Outcome of cryobiopsy | Outcome of EBUS-TBNA/cell block | Concordance or discordance between cryobiopsy and EBUS-TBNA cell block | Number of cryo-biopsies obtained | Cryobiopsy diameter (cm) | EBUS-TBNA biopsy diameter (cm) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 65 | Characterization of lung cancer | Station 7 | Station 7 | Positive for squamous cell lung cancer | Positive for non-small lung cancer (possibly of squamous histology) | Concordance | 3 | 0.42 | 0.15 | No |

| Case 2 | 59 | Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes | Station 7 | Station 7 | Positive for small cell lung cancer | Positive for small cell lung cancer | Concordance | 3 | 0.61 | 0.32 | No |

| Case 3 | 64 | Characterization of enlarged 11Ri station | Station 11Ri | Station 11Ri | Normal lymph node | Normal lymph node | Concordance | 3 | 0.58 | 0.21 | No |

| Case 4 | 53 | Suspected recurrence of lymphoma | Station 7 | Station 7 | Positive for follicular B lymphoma | Suspected lymphoma cells (not suitable for subtyping) | aDiscordance | 3 | 0.53 | 0.20 | Minimal bleeding |

Case 4 (A) PET/CT showing increased FDG uptake in the sub-carinal (7) and right hilar stations. (B) EBUS-TBNA was performed with a 22-gauge needle (EchoTip ProCore: Cook Medical) in station 7 node. (C) Puncture site made by TBNA needle; steps of inserting 1.1mm cryo-probe through the puncture site, (D) tip of the cryo-probe approaching the puncture site, (E) after pushing the probe gently the tip of the cryo-probe is completely inside the node. (F) EBUS image showing the tip of the 1.1mm cryo-probe within the lymph node. (G) Pentax EBUS scope (EB-1970UK) with 1.1mm cryo-probe in the working channel. The tip of the probe has the lymph node tissue obtained by cryobiopsy. (H) Bronchoscopic view of the puncture site after taking cryo-nodal biopsy (no bleeding was observed). (I) Samples obtained from transbronchial mediastinal cryobiopsy. (J) Simple view of cryobiopsy stained with H&E. (K) Microscopic image of the cryobiopsy sample at low magnification (2×) showing an integrated and compact tissue. (L) Microscopic image of cryobiopsy (10×) showing a well-preserved architecture. (M) Simple view of the cell-block obtained by TBNA stained with H&E. (N) Microscopic image (2×) of the biopsy obtained by TBNA where a very fragmented tissue is observed. (O) Microscopic image (10×) of TBNA cell-block with marked artifacts of size, shape, and chromatin density.

Our first case, a 65-year-old woman, heavy ex-smoker, was referred to our IPU due to suspicion of stage IVB lung cancer. The FDG-PET scan showed a superior hilar mass with metabolically active mediastinal lymph nodes and hepatic lesions. The patient underwent EBUS-TBNA and TMC in the same procedure at station 7. The histologic report of the EBUS-TBNA showed adequate amount of non-small cell lung cancer cells possibly deriving from squamous cell lung cancer; the cryobiopsy was also positive for squamous cell lung cancer, but the sample obtained was larger in size, better structured and included more material for molecular characterizations. No complications occurred after the procedure. The second case, a 59-year-old male, former smoker, was admitted to our institution due to worsened cough and weight loss. A large mediastinal lymph node block at station 4R and 7 was observed in the chest CT scan. EBUS-TBNA and TMC were performed at station 7. The cell block obtained from EBUS-TBNA and the cryobiopsy sample were positive for small cell lung cancer. No further complications were seen. The third case, a 64-year-old woman, non-smoker with no medical history of interest, was referred to our IPU due to a 1.5cm 11Ri lymph node seen on a chest CT. Both EBUS-TBNA and TMC showed a good number of lymphocytes in the absence of atypical cellular elements. Nevertheless, the cryobiopsy sample was architecturally better preserved, bigger in size (0.58cm in diameter) and had more than 200 lymphocytes/field; while the EBUS-TBNA cell block measured 0.21cm in diameter and showed a less structured specimen with more artifacts. No complications were observed.

Zhang et al. conducted a randomized trial that included a total of 197 patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA and TMC in the same procedure to assess the diagnostic yield and safety of this technique. For TMC they performed a small incision in the tracheobronchial wall adjacent to the mediastinal lesion using a high-frequency needle-knife; the knife was then replaced by the cryoprobe, and biopsies were performed by cooling down for 7s. In their trial the overall diagnostic yield was 79.9% and 91.8% for TBNA and TMC respectively; while cryobiopsy was more sensitive than TBNA in uncommon tumors (91.7% versus 25%) and benign disorders (80.9% versus 53.2%).5 An important difference in our case series is the way we perform the procedure; we have shown that the high-frequency needle knife is not essential; we eliminated this step of the process by directly introducing the 1.1mm cryo-probe always eco-guided through the puncture site created by the EBUS-TBNA needle; allowing us to perform the procedure in a faster way. The overall procedure time in our series was 22.7±6.3min (range 13.0–41.4min). In the Zhang et al. trial using the high-frequency needle-knife, the overall procedure time was 31.9±9.1min.5 It is important to mention that the Ariza-Pallarés method for performing TMC is mainly based on introducing the cryoprobe always under ultrasound guidance, we do not focus on trying to introduce the cryoprobe through the puncture site only. We are guided by the trace left in the lymph node by the puncture of the EBUS-TBNA, it is key to introduce the cryoprobe at the same angle in which the previous punctures were performed. If the cryoprobe is not inserted at the correct angle, resistance will be felt and the cryoprobe could bend, making the procedure very complex and impossible to complete. It is important to highlight from our method, that every time we obtain a TMC, we immediately return with the EBUS to the punctured station and spend 2min visualizing its ultrasonographic characteristic under Doppler mode, letting us rule out signs of bleeding within the lymph node. Once these signs were ruled out, we proceed to perform the next cryobiopsy.

The TMC samples obtained in our series were adequate for histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry staining. The mean diameter of the samples retrieved from cryobiopsy was 0.54cm; while the mean diameter obtained from the EBUS-TBNA cell block was 0.22cm. Several studies have demonstrated that the addition of mediastinal forceps biopsy under real-time ultrasound guidance to TBNA significantly improved specimen quality and diagnostic yield, particularly in patients with sarcoidosis and lymphoma.6–8 Although this technique is being performed in some IPUs as a new tool when the clinical suspicion is a lymphoproliferative disorder or benign lesions, the procedure lasts longer, in some cases the forceps is not able to pass the bronchial wall and has been reported a lower diagnostic sensitivity as compared to TBNA in malignant nodes.8 The ability of EBUS-TBNA to accurately diagnose and subtype lymphoma has been questioned because of lesser sampling of core tissue, and recent research has highlighted the value of histological specimen rather than TBNA-acquired citology for diagnosing lymphoma.9 In our case series, all procedures were performed under conscious sedation and were well tolerated by the patients, suggesting that moderate sedation, just as we performed conventional EBUS-TBNA, may be sufficient for TMC; however, more efforts are required to create the best and safest protocol for its realization. All four cases were performed using a 22-G needle; this is a novelty of our technique, since most of the published works have used a 19-G needle,10,11 and in some of them, it is mentioned that with smaller diameter needles, it would be complicated to carry out the procedure; therefore, our method shows that it is not essential to use a larger gauge needle to perform TMC, which could favor less invasiveness. We consider that this novel procedure requires a learning curve and should be performed by highly experienced pulmonologists in endoscopic procedures, preferably in a department with a high number of yearly EBUS.

In conclusion, although EBUS-TBNA is the technique of choice for the diagnosis and staging of malignant mediastinal lesions, we believe TMC might provide an additive value to current diagnostic approaches for mediastinal diseases, specifically in cases of uncommon tumors, suspicion of lymphoproliferative disorders or when more biopsy sample is needed for molecular determinations. Our initial experience requires prospective validation in a larger patient cohort to confirm the reliability, reproducibility, and safety of this technique.