Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is considered a T2 inflammatory disease caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus fumigatus (AF) fungal spores. It affects up to 2.5% of patients with persistent asthma and is diagnosed using recommended criteria.1 ABPA pathogenesis is a combination of innate and adaptive allergic immune responses. It is driven by T2 interleukins (ILs), such as IL4 and IL13 cytokines, which activate immunoglobuline-E (IgE)-secreting plasmocytes and promote eosinophilic attraction and IL5 secretion.1,2

Standard treatment includes oral corticosteroids (OCS) and itraconazole.1 Despite this treatment, some patients continue to experience uncontrolled asthma symptoms. The effectiveness of omalizumab and anti-IL5/IL5 receptor (IL5R) in ABPA has been documented in case reports and case series.3–10

We present for the first time the results of a long-term combination of omalizumab and anti-IL5/IL5R in 3 patients treated for severe asthma and ABPA over 2 years.

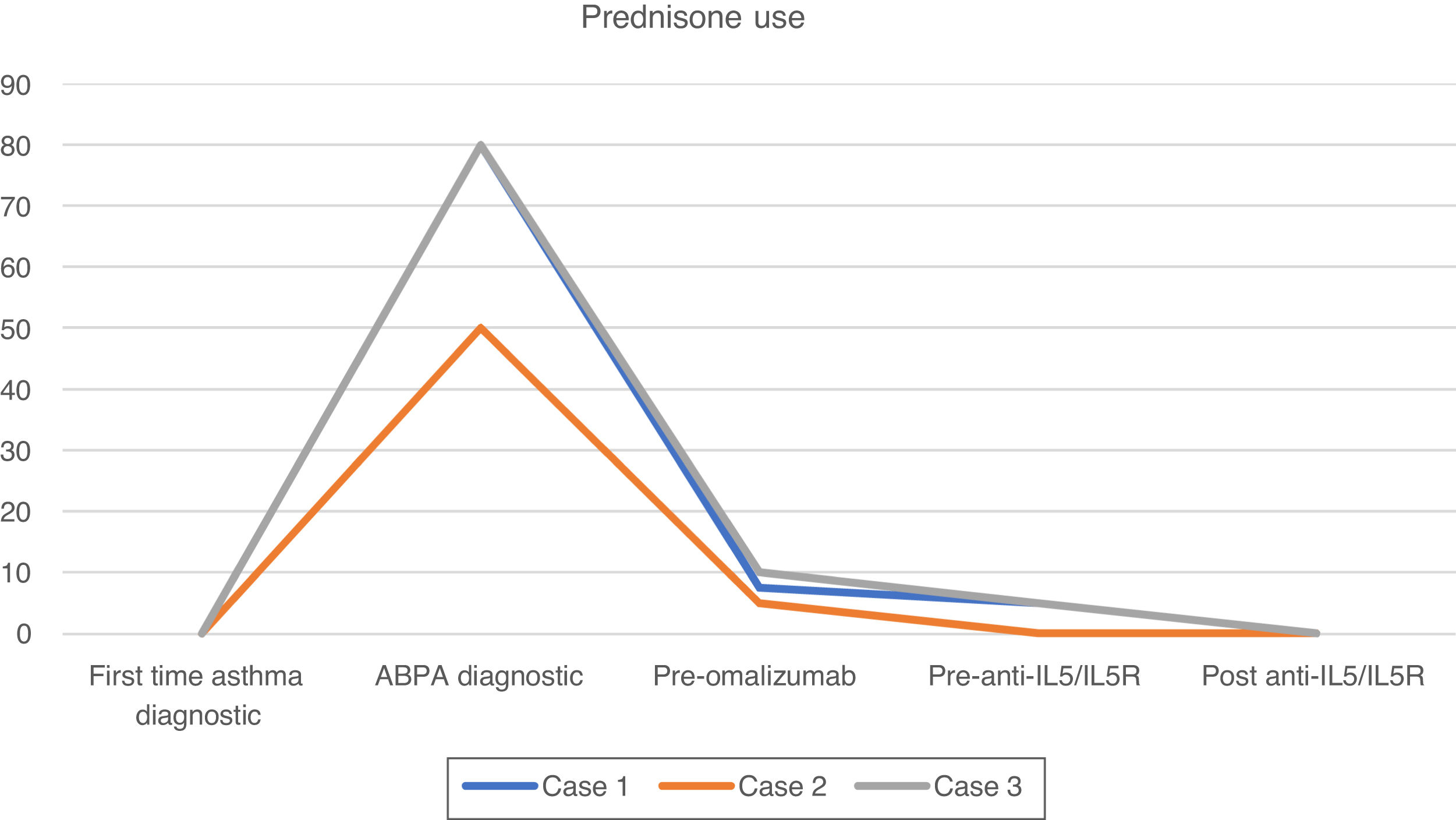

Case 1 is a 67-year-old man who was diagnosed with allergic asthma. He was treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICs) (budesonide 320mcg/12h) and formoterol. His asthma progressively worsened, with 2 exacerbations that required hospitalisation needing prednisone (10mg/24h) in a maintenance regimen. At that time, a complete study showed a positive skin prick test for AF, and blood tests revealed eosinophilia (Fig. 1), high total IgE (1457IU/ml) and elevated specific AF-IgE (16.3kU/L). Computed tomography (CT) showed central bronchiectasis with mucoid impactions in both lower lobes. There were no other concomitant allergic diseases. The patient was thus diagnosed with ABPA.1 Treatment was modified to budesonide (1600 mcg per day), formoterol, tiotropium, montelukast, prednisone (1mg/kg/d) and itraconazole (200mg daily). After 2 months of treatment, prednisone could not be reduced below 7.5mg.

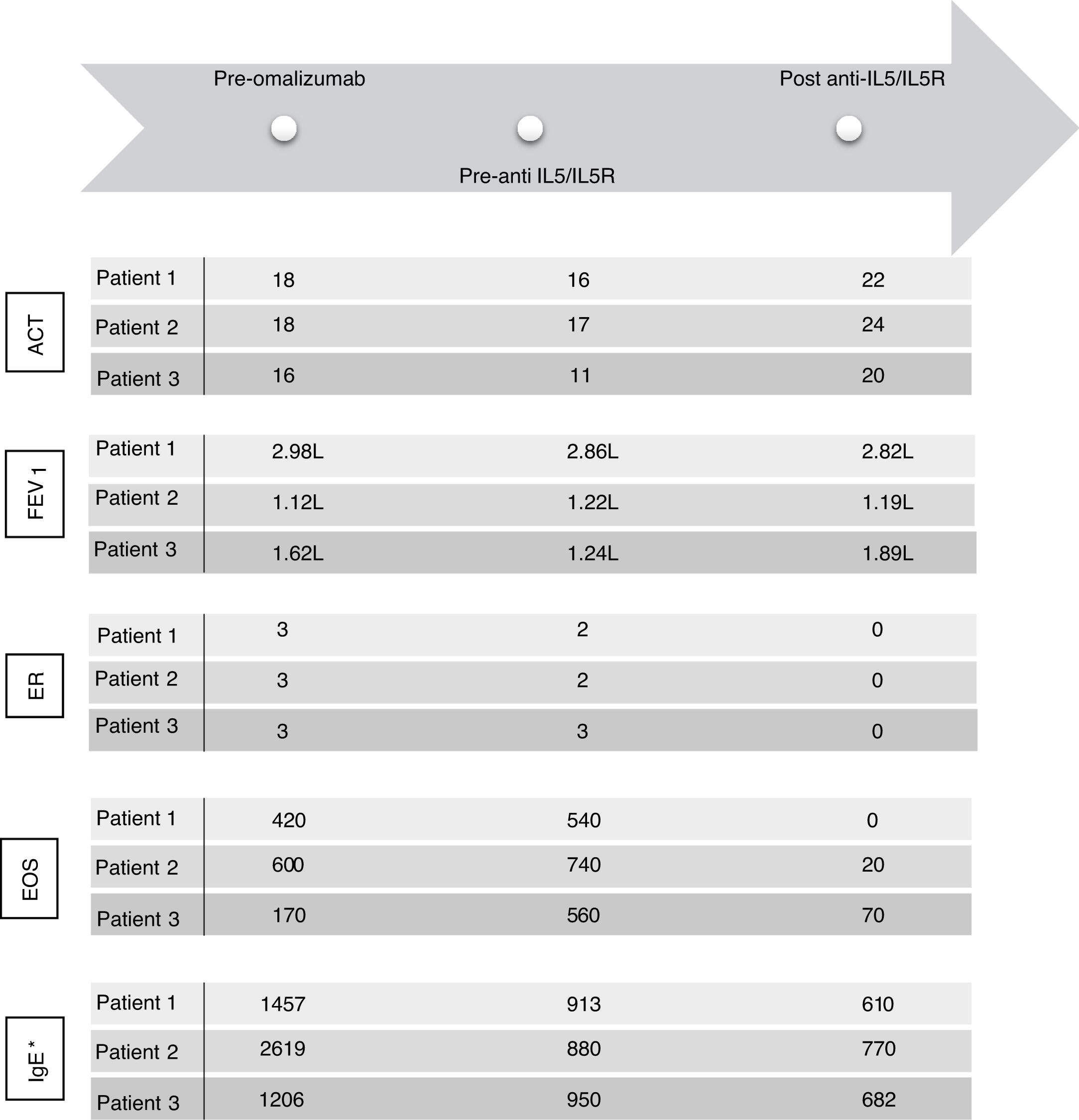

ACT: Asthma Control Test; EOS: eosinophils; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ER: exacerbation rate; IgE: immunoglobulin E (UI/ml)*; IL5: interleukin 5; IL5R: interleukin 5 receptor. FEV1 was calculated in a MasterScreen spirometer (Viasys, Würzburg, Germany) according to ATS/ERS recommendations and GLI reference values for spirometry. * IgE levels measured during treatment with omalizumab concern free and omalizumab-bound IgE.16

In an attempt to reduce OCS, omalizumab (at recomended doses adjusted to IgE level and weight) was prescribed. Over 5 years, his asthma symptoms and exacerbations were controlled, and OCS could be reduced to 2.5mg daily.

After this period, the patient progressively needed slightly higher doses of OCS to maintain control of daily symptoms, and he experienced 2 exacerbations and elevated blood eosinophils (Fig. 1), that required increased doses of OCS to 5mg (Fig. 2). We added benralizumab 30mg/q4w, and q8w after 3 doses. This combined treatment controlled the exacerbations for 1 year and OCS could be supressed, and the total IgE was reduced (610IU/ml). Thus, we decided to reduce the omalizumab doses to 225mg/q2w. One year later, the patient's symptoms remain well controlled without daily OCS and with no exacerbations (Figs. 1 and 2).

Case 2 is a 74-year-old woman diagnosed with allergic asthma. Initially, her asthma was controlled with ICs (fluticasone propionate 500 mcg) and salmeterol; 5 years later, however, her asthma control worsened, with at least 4 exacerbations.

A skin prick test revealed sensitisation to AF, and a blood test showed eosinophilia (Fig. 1), high total IgE (2619IU/ml) and elevated specific AF-IgE (96.1kU/L). CT demonstrated central bilateral bronchiectasis with mucoid impactions. She suffered no other allergic comorbidities. Taking all these data into account, the patient was diagnosed with ABPA.1 Treatment was intensified: fluticasone propionate was increased up to 1000mcg/day and tiotropium was added, as well as prednisone (1mg/kg/d) and oral itraconazole (200mg/d).

After 2 months of treatment, even with prednisone 5mg daily to control asthma symptoms, she experienced 2 exacerbations needing OCS. Therefore, omalizumab was started (at recomended doses adjusted to IgE level and weight), which managed to control her asthma and withdrawn OCS for 9 years.

After this period, the patient had 2 exacerbations, worsening of daily symptoms and eosinophilia (Fig. 1). Then, we started her on benralizumab 30mg/q4w, and q8w after 3 doses.

After 1 year of follow-up, she reported an improvement in symptoms and had no exacerbations. Given that total IgE had been reduced to 770IU/ml, we decided to reduce omalizumab to 225mg/q2w. One year later, she remains asymptomatic.

Case 3 is a 51-year-old man diagnosed with allergic asthma. He was receiving treatment with ICs (fluticasone propionate 1000 mcg) and salmeterol.

Five years later, he had 2 severe exacerbations. A skin prick test for AF was positive, and a blood test revealed eosinophilia (Fig. 1), elevated total IgE (1206IU/ml) and elevated specific AF-IgE (18.1kU/L). CT showed central bronchiectasis and mucoid impaction in the left superior lobe. A diagnosis of ABPA was made.

The patient was given treatment with prednisone (1mg/kg/day), itraconazole (200mg/d) and inhaled tiotropium. Given that there was no clinical improvement (he had 3 exacerbations) and because it was not possible to withdraw OCS, omalizumab at recomended doses adjusted to IgE level and weight was prescribed. One year later, his symptoms had improved, and exacerbations stopped; thus, OCS could be reduced to 5mg daily.

Three years later, he had 3 exacerbations, and eosinophils increased (Fig. 1). Mepolizumab 100mg/q4w was initiated. It led to control of the exacerbations, and OCS was tapered 1 year later. Total IgE was reduced to 682IU/ml. At this time, we reduced the omalizumab dose to 150mg/q2w; 1 year later, symptoms remain controlled.

This group of patients with severe asthma and ABPA improved after being treated with maximum doses of omalizumab. A few years later, however, they experienced unexpected clinical deterioration. Suspecting the involvement of an eosinophil-driven inflammatory pathway, we added anti-IL5/IL5R therapy.

We added anti-IL5/IL5R therapy to omalizumab and maintain the latter because it was initially effective in controlling symptoms (Fig. 1), preventing exacerbations and tapering OCS (Fig. 2) for several years. Combining omalizumab and anti-IL5/IL5R allowed us to control symptoms (Asthma Control Test, ACT: 20–24), reduce exacerbations to zero, improve pulmonary function (Fig. 1) and taper OCS (Fig. 2). This improvement in ABPA control allowed us to step down progressively the dose of omalizumab, therefore reducing costs. This process is still going on, and may allow us to reduce it even more in the future, to the minimun effective dose.

Treating both allergic and eosinophilic pathways could be an effective and safe way to control refractory ABPA and spare OCS. Although the effectiveness of combining omalizumab and anti-IL5/IL5R in ABPA has been documented in case reports,11,12 given that we do not know whether the same effect would be observed if omalizumab had been switched entirely for anti-IL5/IL5R, further mechanistic studies are needed.

Regarding safety, it is relevant that these patients did not present any adverse events during treatment, including bacterial or parasitic infections. There is no evidence in the literature of any adverse events from combining omalizumab with anti-IL5/R.11–15

In conclusion, our results suggest that adding an IL-5/IL5R biologic on top of omalizumab offers the opportunity to control symptoms in patients with severe asthma and ABPA with a partial response to omalizumab.

EthicsThe research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Information revealing the patient's identity has been avoided. All patients have been identified by numbers or aliases and not by their real names.

Study approval statement: Ethics approval was not required because it was a retrospective and observational study. We did not change our daily clinical practice.

Consent to publish statement: The study participants have given their written informed consent to publish their case (including publication of images).

FundingNo funding has been received for this study.

Conflicts of interestNone.