A recent update by international experts in interstitial lung diseases (ILD) representing the American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) and Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ALAT) on selected diagnostic and treatment interventions for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)1–3 and the first guideline on progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) provides new evidence based clinical practice guidelines to the pulmonologists and the community-at-large.3

Methodologically, a systematic review was performed and graded following the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.4 Evidence was discussed by the methodologists and the clinical experts and recommendations were then made by the experts by voting for five options: (1) strong recommendation for, (2) conditional recommendation for, (3) conditional recommendation against, (4) strong recommendation against, and (5) abstention. More than 70% agreement and <20% abstention on the topic results in a strong or conditional recommendation; less than 70% agreement and <20% abstention on the topic yielded no recommendation because of insufficient agreement, and greater than 20% abstentions indicated an insufficient quorum for decision making.

Regarding IPF, a clinically relevant change in diagnosis is the conditional recommendation for the transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC) as an alternative to surgical lung biopsy (SLB) for histopathological diagnosis in newly detected undetermined type of ILD and clinically suspected of having IPF. The relevant research evidence accumulated since the 2018 guidelines and before was exhaustively evaluated obtaining a conditional recommendation for, with 94% votes in favor (70% conditional and 24% strong). However, the Committee emphasized the importance of an experienced bronchoscopy team performing the TBLC according to standardized protocols and an expert pathologist interpreting the samples in each site. Furthermore, the number of samples collected in the TBLC affected the diagnostic yield more than the cryoprobe size. So, ≥3 samples provide an 85% of diagnostic yield compared to 77% or below when less samples were collected. Moreover, when comparing agreement in the diagnostic interpretation of TBLC samples with SLB, differences in diagnostic agreement were reported5,6; assuming the necessity of evaluating this point in further studies. Even so, for the centers that commonly use TBLC for the ILD diagnosis, this technique is cost effective and less invasive than SLB in selected cases.6 Nevertheless, the quality of evidence to recommend TBLC as an alternative to SLB in newly suspected IPF cases with indeterminate UIP or non-UIP radiological pattern at the chest high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan is very low for all outcomes, because of limited clinical studies and inconsistencies across studies. Other important updated IPF diagnostic points are: (1) probable usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) radiologic pattern could be diagnostic of IPF without an histologic sample in an appropriate clinical context and (2) an alternative diagnosis on HRCT (high resolution computed tomography) with an histologic probable UIP pattern is now considered as “indeterminate for IPF” instead of non-IPF as reported in the 2018 guideline,1 because of the possible similar IPF disease behavior and outcomes in some patients. Concerning the first point, the four HRCT patterns defined for the IPF diagnosis1 (UIP, probable UIP, indeterminate for UIP and alternative diagnosis) are the same in the new guideline3; however, when probable UIP radiologic pattern is observed, a histologic confirmation is unnecessary if the clinical probability for an alternative diagnosis is low.7,8 However, we highlight the relevance of deeply exploring an alternative fibrotic ILD diagnosis and individually analyzing the need for bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy specially to rule out fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).9 Finally, the utility of genomic classifier test (transcriptome RNA sequencing) for IPF diagnosis was analyzed.4 No recommendation for or against to use a genomic classifier test (transcriptome RNA sequencing) to diagnose UIP in patients with undetermined type of ILD who undergoing transbronchial forceps biopsy, because of insufficient agreement among the committee. Additional studies in the clinical setting are suggested to better analyze its use for IPF diagnosis.10 Considering IPF treatment, no changes in recommending anti-fibrotic medication have been made3; however, the consensus suggested not treating IPF patients with antacid medication or referring for antireflux surgery for the purpose of improving respiratory outcomes. The committee emphasized the possible beneficial effects of antacid therapy in IPF patients with confirmed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), with very low quality of evidence without reaching a statistical significance.11,12 Therefore, the antireflux treatment according to GERD-specific guidelines would be considered to improve GERD-related outcomes independently of respiratory ones and looking forward to the results of the TIPAL trial.

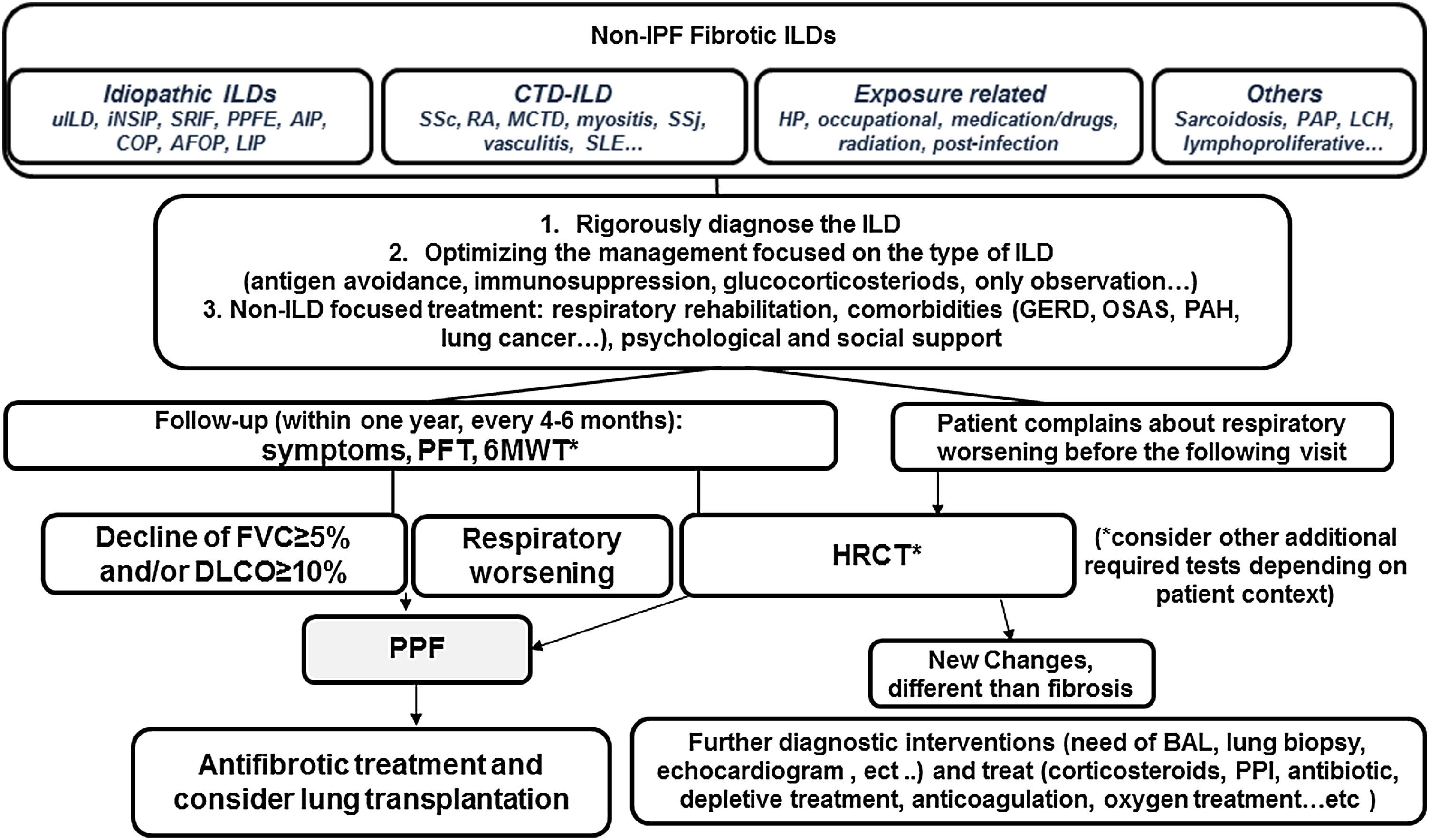

The guideline addressed a necessary consensual definition and criteria of progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) and made an exhaustive revision of the antifibrotic treatment in progressive fibrotic ILDs different to IPF. PPF definition was made considering the common clinical, physiological and/or radiological behavior of patients that present some non-IPF fibrotic ILDs that evolve fibrotic progression and poor prognosis despite the treatment received depending on the ILD diagnosis. Standardizing the concept is a crucial starting point for advancing globally in the clinical and research settings.13 PPF was defined as at least two of the following three criteria occurring within the past year with no alternative explanation: 1. worsening of respiratory symptoms, 2. physiological disease progression defined as absolute decline in FVC of ≥5% predicted either absolute decline of ≥10% predicted in DLCO (corrected for Hb and excluding alternative causes of decline), 3. radiological worsening with one or more of the following HRCT signs increased extent: traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis, new ground-glass opacity with traction bronchiectasis, new fine reticulation, increased extent or increased coarseness of reticular abnormality, new or increased honeycombing and/or increased lobar volume loss. It is noteworthy that the wording “within one year” implies that criteria of fibrotic progression may be identified at any time (three, six, nine months,…) during the past year, and, therefore, there is no reason to wait the full year for considering antifibrotic treatment of PPF (Fig. 1). Regarding evidence-based recommendations for antifibrotic treatment of PPF, the review of research publications was made paying attention to the different inclusion criteria and lacking a standard definition of PPF in the different clinical trials. Then, a conditional recommendation for nintedanib was made for patients who have failed standard management for fibrotic ILD (62% conditional votes for, 29% strong for, 9% abstention). The recommendation was discussed reviewing the INBUILD trial and the post hoc analysis published.14 Concerning pirfenidone, guideline recommend further research into the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of pirfenidone in non-IPF ILD in general and in specific types manifesting PPF, due to the lack of high evidence despite two small clinical trials15 (conditional recommendation for (62%), 38% abstention). The guideline emphasizes the need of rigorously diagnose and manage the type of ILD, trying the standard management (antigen avoidance, immunosuppression, or only observation), to stabilize or reverse initial disease or trigger, before initiating antifibrotic therapy. Furthermore, the continuing research looking for the reasons of fibrosis progression has been also suggested, identifying specific types of ILD susceptible to be treated in a specific timing and finding good and easy biomarkers of diagnosis and progression.

Simplified algorithm for clinical management of progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF). Based on the narrative text of the 2022 published guideline document.AFOP: acute fibrinous organizing pneumonia; AlP: acute interstitial pneumonia; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; COP: cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis; PPI: proton pump inhibitors; DIP: descamative interstitial pneumonia; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; PPFE: pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; OSAS: obstructive sleep apeas syndrome; LCH: Langerhans cell histiocytosis; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; PAP: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis; CTD-ILD: conective tissue disease associated ILD; SSc: systemic sderosis; RA: rheumatoid artritis; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; SSj: Sjögren syndrome; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; PFT: pulmonary function tests; 6MWT: 6 minutes walking test.

Prof. G. Raghu has received personal fees for scientific advise or research grants from BMS, Boehringer Ing, Bellerophan, Fibrogen, Nitto, Biogen, Roche-Genentech, Avalyn, NIH.

Prof. M. Molina-Molina has received personal fees for research grants or scientific advise from Boehringer Ing, Roche, Ferrer, Esteve-Teijin, Chiesi.