Measures of health related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) can help to determine the impact of the disease and provide an important insight into the intervention outcomes. There is few data regarding this issue in the literature. The aim of this study is to assess the relationship between HRQoL and gender, functional parameters and history of hospitalizations in patients with AATD.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study of 26 patients with severe AATD recruited in the pulmonology outpatient clinic at a tertiary care medical center. Social-demographic, clinical and functional parameters were recorded and HRQoL was assessed with the Portuguese version of the medical outcome study short form-36 (SF-36) self-administered questionnaire.

ResultsOlder patients, females and patients with at least one hospitalization in the previous year due to respiratory disease had statistical lower scores in some dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire. Superior FEV1 and higher distance mark in the 6-min walking test distance influenced positively several dimensions of the questionnaire. Higher scores in the mMRC scale influenced negatively the HRQoL.

ConclusionsThese data suggests that older and female patients with AATD have worse HRQoL. Hospitalizations and functional markers of respiratory disease progression influenced negatively the HRQoL, suggesting that the SF-36 questionnaire could be useful as an outcome for AATD patients with lung involvement.

Las medidas de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) pueden ayudar a determinar los efectos de la enfermedad de los pacientes con déficit de α1-antitripsina (DAAT) y proporcionar una perspectiva valiosa de los resultados de las intervenciones. Este tema se ha abordado poco en la literatura, y el objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar si existe alguna relación entre la CVRS y el sexo, los parámetros funcionales y los antecedentes de hospitalización de los pacientes con DAAT.

MétodosPara este estudio transversal se reclutaron 26 pacientes con DAAT grave que eran atendidos en las consultas externas de neumología de un hospital terciario. Se registraron parámetros sociodemográficos, clínicos y funcionales, y se evaluó la CVRS mediante la versión portuguesa del cuestionario de salud SF-36.

ResultadosLos pacientes de mayor edad, de sexo femenino y los que habían sido hospitalizados por enfermedad respiratoria al menos una vez durante el año anterior mostraron puntuaciones más bajas en algunas dimensiones del cuestionario SF-36. Los valores más altos de FEV1 y distancias recorridas más largas en la prueba de la marcha de 6min tuvieron una influencia positiva sobre varias dimensiones del cuestionario, mientras que las puntuaciones más altas en la escala MRCm influyeron negativamente en la CVRS.

ConclusionesLos resultados muestran que la CVRS de los pacientes de mayor edad y las mujeres con DAAT es peor. Las hospitalizaciones y los marcadores funcionales de progresión de la enfermedad respiratoria tuvieron una influencia negativa sobre la CVRS, lo que indica que el cuestionario SF-36 podría ser de utilidad como medida de resultados de los pacientes con DAAT y afectación pulmonar.

Alpha 1-Antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), though often under-diagnosed, is one of the most common genetic respiratory disorders worldwide, affecting from 1 in 2000 to 1 in 5000 individuals.1 AATD predisposes to lung and liver disease and some other conditions.2,3

Alpha 1-Antitrypsin is the prototype member of the serine protease inhibitor (serpin) superfamily of proteins, and is caused by mutations in the SERPINA1 gene located in the long arm of chromosome 14.1,4 This genetic defect results in decreased serum levels of α1-antitrypsin, leading to low alveolar concentrations and protease excess, causing emphysema.1,4

In chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), measures of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) are frequently used as descriptive instruments or as outcome measures.5 Since no cure has yet been found for most chronic respiratory diseases, a major goal of care is to improve HRQoL.

Given the lack of studies assessing HRQoL in patients with AATD and the increasing importance of HRQoL measures, the aim of this study was to assess the relationship between HRQoL and gender, functional parameters and history of hospitalizations (previous year) in patients with AATD.

MethodsStudy Design and SettingThis is a cross-sectional study of patients with AATD recruited from January to June 2013 (6 months) in the pulmonology outpatient clinic at the University Hospital São João, a tertiary hospital. The research protocol was submitted to and approved by the local research ethics committee.

PatientsThe sample included 26 consecutive patients attending the pulmonology outpatient clinic, with an AATD diagnosis confirmed by genetic analysis (genotypes ZZ and SZ). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Illiterate patients and those with physical and mental disabilities prior to the diagnosis of AATD were excluded.

Clinical and Pulmonary Function AssessmentSocial-demographic data were recorded, namely age, gender, educational level, social and employment status. Patients also underwent clinical evaluation that included dyspnea severity measured on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale,6 assessment of smoking status, presence of significant co-morbidities and current medication. The results from the genetic analysis were also retrieved. The number of hospitalizations due to respiratory disease in the previous year was retrospectively analyzed using clinical records. Each patient was tested for spirometry and lung volumes (MasterScreen™ Body; Jaeger, Würzburg, Germany) according to international guidelines.7,8 The 6-min walking test (6MWT) was performed using the methodology described by the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society.9

Quality of LifeHRQoL was assessed using the Portuguese version of the short form-36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire.10,11 The SF-36 questionnaire was used as it is considered a well-researched and reliable instrument that has been culturally adapted and validated for the Portuguese population.11 Moreover, it has been used as an outcome measure in different studies in chronic respiratory diseases, such a COPD.

The questionnaire was administered during the patient's first visit to the pulmonology outpatient clinic in the study period.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are described with their mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables are described by their relative frequencies (in percentage).

The independent samples t-test was used to compare the SF-36 scores between genders, genotypes, patients untreated vs patients treated with augmentation therapy, and patients without vs patients with hospitalizations due to respiratory disease in the previous year. Linear regression was used to analyze the association between the SF-36 scores and age, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and 6-min walking test distance (6MWTD).

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

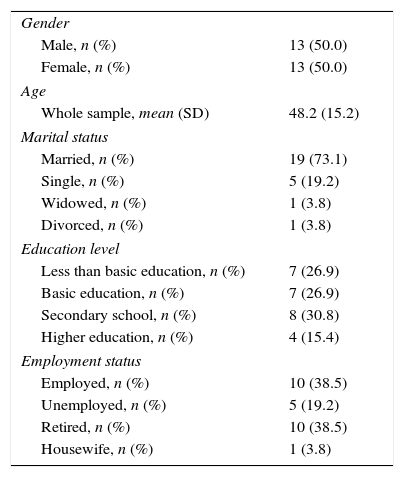

ResultsSocio-demographic characteristics of AATD patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the sample population was 48.2 years, 73.1% (Standard Error, SE=0.09) of the patients were married and 19.2% (SE=0.08) single. Regarding the education level, 46.2% (SE=0.10) had more than basic education.

Socio-demographic Characteristics.

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (50.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (50.0) |

| Age | |

| Whole sample, mean (SD) | 48.2 (15.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married, n (%) | 19 (73.1) |

| Single, n (%) | 5 (19.2) |

| Widowed, n (%) | 1 (3.8) |

| Divorced, n (%) | 1 (3.8) |

| Education level | |

| Less than basic education, n (%) | 7 (26.9) |

| Basic education, n (%) | 7 (26.9) |

| Secondary school, n (%) | 8 (30.8) |

| Higher education, n (%) | 4 (15.4) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed, n (%) | 10 (38.5) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 5 (19.2) |

| Retired, n (%) | 10 (38.5) |

| Housewife, n (%) | 1 (3.8) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

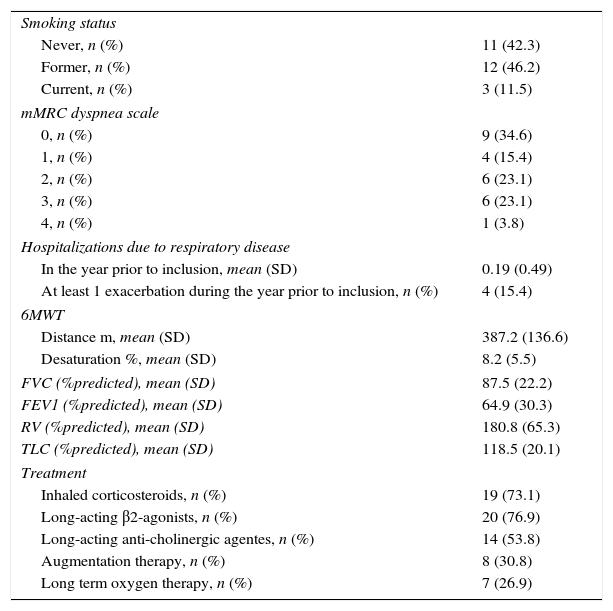

The main baseline clinical characteristics of patients are described in Table 2. The AAT phenotype was ZZ for 15 patients (57.7%, SE=0.10) and SZ for 11 (42.3%, SE=0.10). All patients had lung involvement with emphysema or bronchiectasis on chest tomography. The majority of patients (80.8%, SE=0.08) had respiratory symptoms: dyspnea in 18 (69.2%, SE=0.09), chronic bronchitis in 16 (61.5%, SE=0.10) and wheezing in 10 (38.5%, SE=0.10). Liver disease was found in 50% (SE=0.10) of patients.

Clinical Characteristics.

| Smoking status | |

| Never, n (%) | 11 (42.3) |

| Former, n (%) | 12 (46.2) |

| Current, n (%) | 3 (11.5) |

| mMRC dyspnea scale | |

| 0, n (%) | 9 (34.6) |

| 1, n (%) | 4 (15.4) |

| 2, n (%) | 6 (23.1) |

| 3, n (%) | 6 (23.1) |

| 4, n (%) | 1 (3.8) |

| Hospitalizations due to respiratory disease | |

| In the year prior to inclusion, mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.49) |

| At least 1 exacerbation during the year prior to inclusion, n (%) | 4 (15.4) |

| 6MWT | |

| Distance m, mean (SD) | 387.2 (136.6) |

| Desaturation %, mean (SD) | 8.2 (5.5) |

| FVC (%predicted), mean (SD) | 87.5 (22.2) |

| FEV1 (%predicted), mean (SD) | 64.9 (30.3) |

| RV (%predicted), mean (SD) | 180.8 (65.3) |

| TLC (%predicted), mean (SD) | 118.5 (20.1) |

| Treatment | |

| Inhaled corticosteroids, n (%) | 19 (73.1) |

| Long-acting β2-agonists, n (%) | 20 (76.9) |

| Long-acting anti-cholinergic agentes, n (%) | 14 (53.8) |

| Augmentation therapy, n (%) | 8 (30.8) |

| Long term oxygen therapy, n (%) | 7 (26.9) |

Abbreviations: 6MWT, six-minute walk test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; RV, residual volume; SD, standard deviation; TLC, total lung capacity.

Most patients had a ventilatory obstructive pattern, with a mean FEV1 of 64.9% predicted, and 38.5% (SE=0.10) of patients with a FEV1 of less than 50% predicted. The mean 6MWTD was 387.2 meters, and the mean desaturation was 8.2%.

During the study period, 23 patients (88.5%, SE=0.06) were treated with long-acting bronchodilators, whereas 19 (73.1%, SE=0.09) also received inhaled corticosteroids. Seven patients (26.9%, SE=0.09) were undergoing long-term oxygen therapy. Eight patients (30.8%, SE=0.09) were given augmentation therapy during the study period according to a 60mg/kg weekly administration regimen, in accordance with the guidelines published by the Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirurgía Torácica (SEPAR).12 Patients receiving augmentation therapy had more severe airflow limitation than untreated patients (P<0.05), and all of them presented a ZZ phenotype.

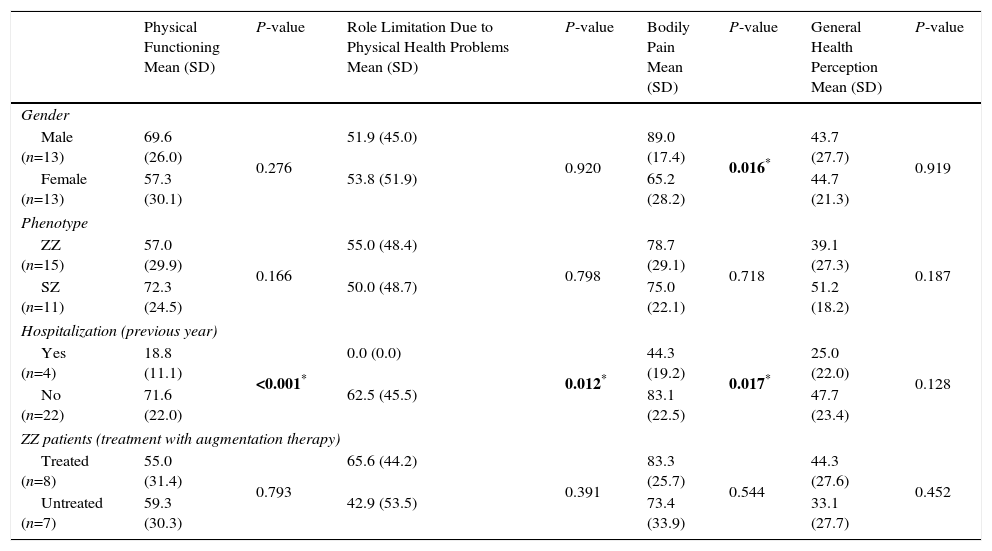

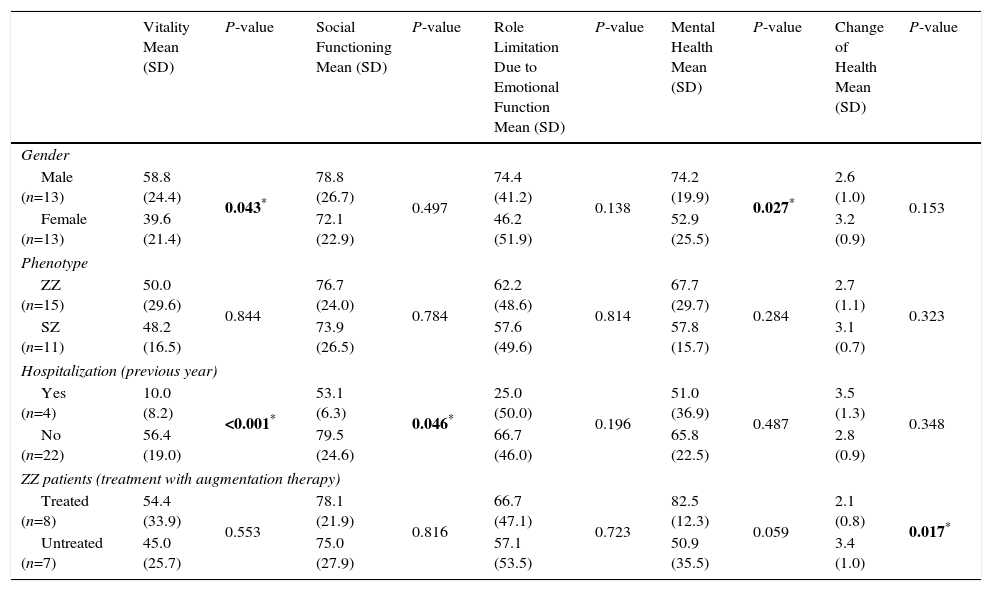

The association between the SF-36 dimensions and gender, phenotype, hospitalizations (in the previous year) and treatment with augmentation therapy is shown in Tables 3 and 4. A statistically significant difference between genders was found in 3 dimensions of the questionnaire, bodily pain (89.0 vs 65.2; P=0.016), vitality (58.8 vs 39.6; P=0.043) and mental health (74.2 vs 52.9; P=0.027), with female gender presenting lower scores in both dimensions. Patients with at least 1 hospitalization in the previous year due to respiratory disease had significantly lower scores in several dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire (physical functioning, P≤0.001; role limitation due to physical health problems, P=0.012, bodily pain, P=0.017; vitality, P<0.001; social functioning, P=0.046). ZZ patients receiving augmentation therapy had significantly higher scores in the change of health item than ZZ patients no receiving this therapy (2.0 vs 3.0, P=0.021).

SF-36 Dimensions (Physical Health) and Gender, Phenotype, Hospitalizations (Previous Year) and Treatment With Augmentation Treatment Status.

| Physical Functioning Mean (SD) | P-value | Role Limitation Due to Physical Health Problems Mean (SD) | P-value | Bodily Pain Mean (SD) | P-value | General Health Perception Mean (SD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male (n=13) | 69.6 (26.0) | 0.276 | 51.9 (45.0) | 0.920 | 89.0 (17.4) | 0.016* | 43.7 (27.7) | 0.919 |

| Female (n=13) | 57.3 (30.1) | 53.8 (51.9) | 65.2 (28.2) | 44.7 (21.3) | ||||

| Phenotype | ||||||||

| ZZ (n=15) | 57.0 (29.9) | 0.166 | 55.0 (48.4) | 0.798 | 78.7 (29.1) | 0.718 | 39.1 (27.3) | 0.187 |

| SZ (n=11) | 72.3 (24.5) | 50.0 (48.7) | 75.0 (22.1) | 51.2 (18.2) | ||||

| Hospitalization (previous year) | ||||||||

| Yes (n=4) | 18.8 (11.1) | <0.001* | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.012* | 44.3 (19.2) | 0.017* | 25.0 (22.0) | 0.128 |

| No (n=22) | 71.6 (22.0) | 62.5 (45.5) | 83.1 (22.5) | 47.7 (23.4) | ||||

| ZZ patients (treatment with augmentation therapy) | ||||||||

| Treated (n=8) | 55.0 (31.4) | 0.793 | 65.6 (44.2) | 0.391 | 83.3 (25.7) | 0.544 | 44.3 (27.6) | 0.452 |

| Untreated (n=7) | 59.3 (30.3) | 42.9 (53.5) | 73.4 (33.9) | 33.1 (27.7) | ||||

SF-36 Dimensions (Mental Health, Change of Health Item) and Gender, Phenotype, Hospitalizations (Previous Year) and Treatment With Augmentation Treatment Status.

| Vitality Mean (SD) | P-value | Social Functioning Mean (SD) | P-value | Role Limitation Due to Emotional Function Mean (SD) | P-value | Mental Health Mean (SD) | P-value | Change of Health Mean (SD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male (n=13) | 58.8 (24.4) | 0.043* | 78.8 (26.7) | 0.497 | 74.4 (41.2) | 0.138 | 74.2 (19.9) | 0.027* | 2.6 (1.0) | 0.153 |

| Female (n=13) | 39.6 (21.4) | 72.1 (22.9) | 46.2 (51.9) | 52.9 (25.5) | 3.2 (0.9) | |||||

| Phenotype | ||||||||||

| ZZ (n=15) | 50.0 (29.6) | 0.844 | 76.7 (24.0) | 0.784 | 62.2 (48.6) | 0.814 | 67.7 (29.7) | 0.284 | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.323 |

| SZ (n=11) | 48.2 (16.5) | 73.9 (26.5) | 57.6 (49.6) | 57.8 (15.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | |||||

| Hospitalization (previous year) | ||||||||||

| Yes (n=4) | 10.0 (8.2) | <0.001* | 53.1 (6.3) | 0.046* | 25.0 (50.0) | 0.196 | 51.0 (36.9) | 0.487 | 3.5 (1.3) | 0.348 |

| No (n=22) | 56.4 (19.0) | 79.5 (24.6) | 66.7 (46.0) | 65.8 (22.5) | 2.8 (0.9) | |||||

| ZZ patients (treatment with augmentation therapy) | ||||||||||

| Treated (n=8) | 54.4 (33.9) | 0.553 | 78.1 (21.9) | 0.816 | 66.7 (47.1) | 0.723 | 82.5 (12.3) | 0.059 | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.017* |

| Untreated (n=7) | 45.0 (25.7) | 75.0 (27.9) | 57.1 (53.5) | 50.9 (35.5) | 3.4 (1.0) | |||||

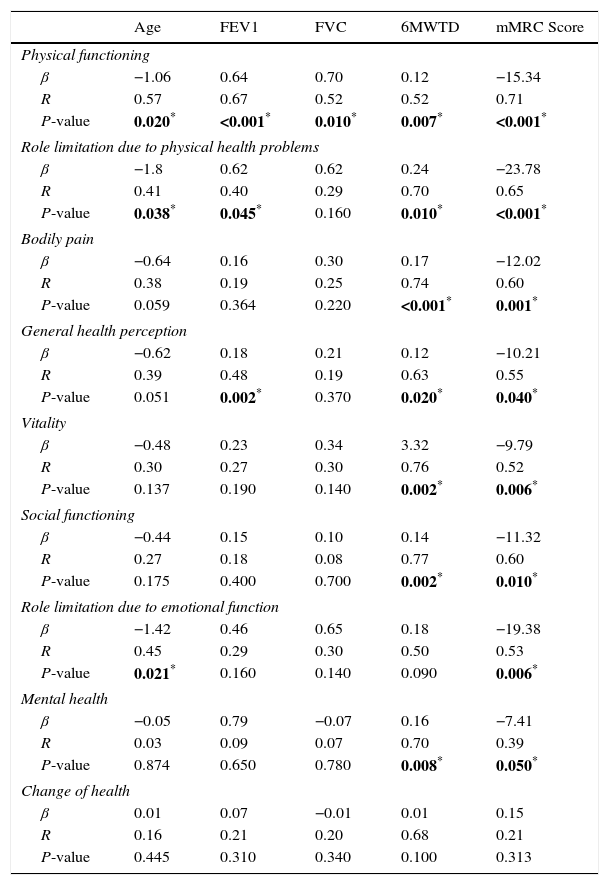

Table 5 presents the correlation of the SF-36 score with age, FEV1, FVC, 6MWTD and mMRC score. Older age negatively influenced 3 dimensions of the score (physical functioning, β=−1.06, P=0.020; role limitation due to physical health problems, β=−1.8, P=0.038; role limitation due to emotional function, β=−1.42, P=0.021). A positive correlation between FEV1 and physical functioning (β=0.64, P<0.001), role limitation due to physical health problems (β=0.62, P=0.045) and general health perception (β=0.18, P=0.002) was found. A higher distance mark in the 6MWT positively influenced several dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire (physical functioning, β=0.12, P=0.007; role limitation due to physical health problems, β=0.24, P=0.010; bodily pain, β=0.17, P<0.001; general health perception, β=0.12, P=0.020; vitality, β=3.32, P=0.002; social functioning, β=0.14, P=0.002; mental health, β=0.16, P=0.008). Higher mMRC scores negatively influenced the 8 dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire, as shown in Table 5.

SF-36 Dimensions and Age, FEV1, FVC, 6MWTD and mMRC Score.

| Age | FEV1 | FVC | 6MWTD | mMRC Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | |||||

| β | −1.06 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.12 | −15.34 |

| R | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.71 |

| P-value | 0.020* | <0.001* | 0.010* | 0.007* | <0.001* |

| Role limitation due to physical health problems | |||||

| β | −1.8 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.24 | −23.78 |

| R | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.70 | 0.65 |

| P-value | 0.038* | 0.045* | 0.160 | 0.010* | <0.001* |

| Bodily pain | |||||

| β | −0.64 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.17 | −12.02 |

| R | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.74 | 0.60 |

| P-value | 0.059 | 0.364 | 0.220 | <0.001* | 0.001* |

| General health perception | |||||

| β | −0.62 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.12 | −10.21 |

| R | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.63 | 0.55 |

| P-value | 0.051 | 0.002* | 0.370 | 0.020* | 0.040* |

| Vitality | |||||

| β | −0.48 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 3.32 | −9.79 |

| R | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| P-value | 0.137 | 0.190 | 0.140 | 0.002* | 0.006* |

| Social functioning | |||||

| β | −0.44 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.14 | −11.32 |

| R | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 0.60 |

| P-value | 0.175 | 0.400 | 0.700 | 0.002* | 0.010* |

| Role limitation due to emotional function | |||||

| β | −1.42 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.18 | −19.38 |

| R | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.53 |

| P-value | 0.021* | 0.160 | 0.140 | 0.090 | 0.006* |

| Mental health | |||||

| β | −0.05 | 0.79 | −0.07 | 0.16 | −7.41 |

| R | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 0.39 |

| P-value | 0.874 | 0.650 | 0.780 | 0.008* | 0.050* |

| Change of health | |||||

| β | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| R | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.68 | 0.21 |

| P-value | 0.445 | 0.310 | 0.340 | 0.100 | 0.313 |

P<0.05 (statistically significant).

Abbreviations: 6MWTD, six-minute walk test distance; β, beta coefficient of the linear regression; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; mMRC, Modified Medical Research Council; R, correlation coefficient of the linear regression; SF-36, Short Form-36 self administered questionnaire.

In this paper, we describe a cross-sectional study that analyses the relationship between HRQoL and social-demographic, clinical and functional parameters in patients with AATD. All the patients included in this study were routinely followed-up in the pulmonology outpatient clinic and had documented lung involvement, with most of them having a ventilatory obstructive pattern. The cross-sectional data available found some significant statistical correlations.

In this study, female patients had significantly lower scores in 2 dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire. In COPD patients, published data shows that women have higher levels of anxiety and depression and worse symptom-related quality of life than their male counterparts; nevertheless, gender-related determinants of HRQoL in COPD are not fully understood.13

A higher score in the SF-36 change of health item was found in ZZ patients receiving augmentation therapy. However, the difference found is of little value outside a randomized controlled double-blinded trial.

A positive correlation between FEV1, 6MWTD and numerous dimensions of the SF-36 was found, and higher mMRC scores negatively influenced all dimensions of HRQoL. Additionally, we found significantly lower scores in several dimensions of the SF-36 questionnaire in patients with at least 1 hospitalization in the previous year due to respiratory disease. Thus, a significant association between different markers of respiratory disease progression and several domains of the SF-36 questionnaire was identified in this patient sample. In line with these findings, published data shows that the SF-36 questionnaire could be a useful instrument to predict exacerbations in COPD patients, and that it correlates with the mMRC score and the 6MWTD in these patients.14,15

As the present study relied on cross-sectional data, unequivocal determinations of cause-and-effect are not possible. Furthermore, a larger sample would be needed to gain a better understanding of the relationship between the different markers of disease progression and outcomes and the SF-36 domains in a multivariate analysis.

HRQoL questions about perceived physical and mental health and function are an important component of health surveillance, and are considered indicators of service needs and intervention outcomes.16 Measuring HRQoL in AATD patients can help determine the impact of the disease and provide valuable insight into intervention outcomes.16 What little data is available on this subject is based on AATD National Registries.17,18 Despite its limitations, the present study represents an important step forward, since it analyzes the relationship between several characteristics of AATD patients and HRQoL dimensions. The results also suggest that the SF-36 questionnaire could be useful as a patient reported outcome for AATD patients with lung involvement.

ConclusionsOlder and female patients with AATD have worse HRQoL when assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire. The present study found an association between different markers of respiratory disease progression and worse HRQoL in patients with AATD and lung involvement. Despite these findings, correlations between HRQoL outcome measures and clinical data have to be further investigated with prospective studies.

Given the scarcity of studies in HRQoL in patients with AATD, our findings can play an important role in the management of these patients.

FundingThe authors declare they have received no funding.

Author ContributionsMTR contributed to study design, data collection, and authorship. EC was involved in study design, performed data collection and reviewed the manuscript. LR contributed to authorship and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. MS was involved in study design, performed data collection, contributed to authorship and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, and are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Torres Redondo M, Campoa E, Ruano L, Sucena M. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en pacientes con déficit de alfa-1 antitripsina: estudio transversal. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53:49–54.