Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be one of the infectious diseases with the greatest morbidity in the world. Its incidence in Spain remains high due to constant demographic changes, and a greater proportion of the TB population are immigrants, who account for up to 30%–40% of patients diagnosed with TB.1–4 Pulmonary TB is the most common form of involvement, but lesions can occur in other body systems.

We report the case of a 19-year-old Bulgarian woman, resident in Spain for 3 years. She had been evaluated in the clinic for iron-deficiency anemia and abdominal pain 6 months previously. An abdominal ultrasound was requested, which revealed slight splenomegaly and lymphadenopathies in the hepatic hilum and in the right iliac fossa. The patient did not return for a follow-up examination.

On the day of admission, she came to the emergency room with abdominal pain in the epigastrium and mesogastrium that had worsened during the previous week, fever, night sweats, and occasional dry cough. She reported loss of appetite with a 10kg weight loss in the last 3 months. Examination revealed bilateral supraclavicular and laterocervical lymphadenopathies, and pain on palpation of the mesogastrium, with no other significant findings.

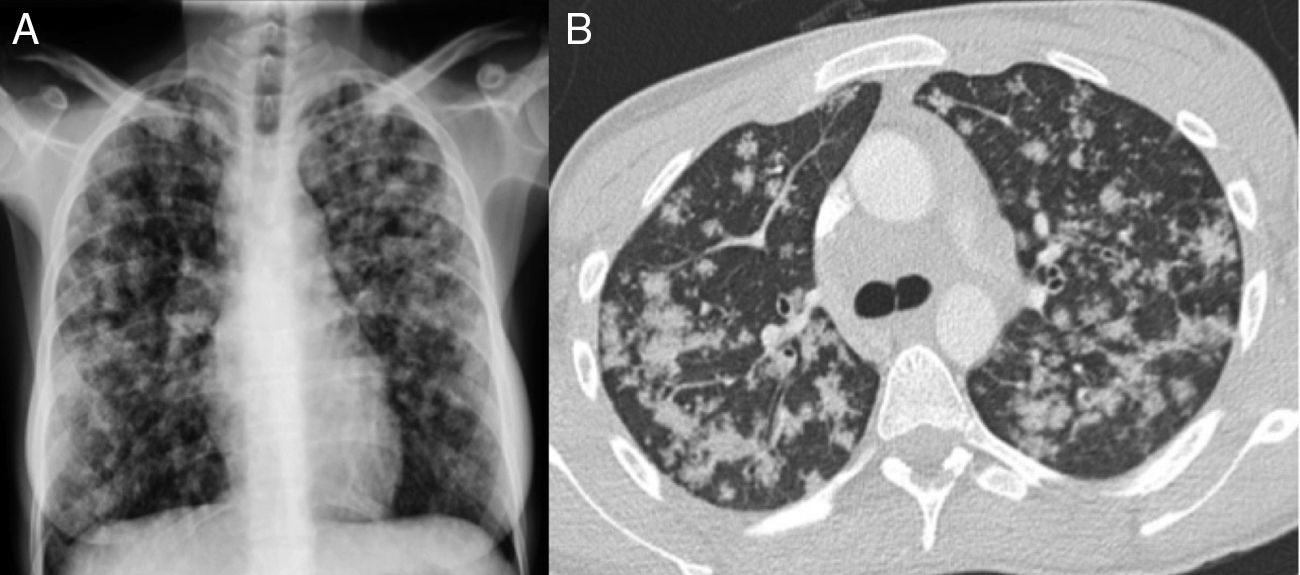

Blood tests were significant for CRP 24.4mg/dl and microcytic anemia 94g/l. Other blood count, coagulation, renal and hepatic parameters were normal. HIV, HBV, HCV and HAV serologies were negative. Standard chest radiograph (Fig. 1A) showed a bilateral diffuse micronodular pattern. A computed tomography of the cervical spine, chest, and abdomen was significant for posterior cervical lymphadenopathies in middle and low jugular chains, some of which were necrotic; the lungs (Fig. 1B) showed multiple irregular nodules randomly distributed predominantly in the upper and middle fields, with mediastinal lymphadenopathies in the hepatic hilum, celiac trunk, and para-aortic and inter-aortocaval nodes adjacent to the iliac chains. Given these findings, we requested an induced sputum test, which confirmed the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on Ziel-Nielssen staining in 3 different samples with subsequent growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on culture.

Posteroanterior chest X-ray (A) with patchy pseudonodular opacities, predominantly in the middle and upper fields. No pleural effusion or mediastinal widening is seen. Chest CT cross-sectional slice (B) showing centrolobular pulmonary opacities with a tendency to coalesce, predominantly in the upper and middle fields.

Treatment began with isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampicin and pyrazinamide. No resistances were observed to any of these drugs. The patient presented clinical and radiological improvement over the following weeks. After 2 months of treatment, negativization of AFB in sputum was confirmed, and treatment with isoniazid and rifampin continued for 4 more months.

TB is still present in our environment. The incidence rate of TB in the native Spanish population has declined in recent years. However, migratory flows observed since the beginning of the 21st century have led to an increase in the proportion of immigrants among the total number of TB cases diagnosed in our country, especially among those coming from countries with a high prevalence of TB.2–5

The incidence and prevalence of this disease are directly related to the degree of poverty, and eradication requires prevention, early diagnosis, and institutional support.1,4 Some circumstances, such as coinfection with HIV, the increase in drug resistance, and geographical mobility complicate the efforts of international agencies to control this disease.2 TB with pulmonary involvement is the most common form of presentation, and in extrapulmonary sites, the lymph nodes are the most common, followed by pleural, osteoarticular, miliary, genitourinary, peritoneal and central nervous system involvement. Symptoms include: fever; night sweats, either isolated or associated with fever; cough, which may be absent at the onset of the disease and be productive or not; dyspnea, if there is extensive involvement of the lung parenchyma; and anorexia and weight loss.1,5 However, multiple clinical manifestations have been described, depending on the affected organ.1

Pulmonary TB can occur along with involvement at other levels, spreading by contiguity, hematogenous dissemination, or by swallowing infected lung secretions. Patients with abdominal involvement, as in our case, usually present with pain, anorexia, weight loss, and fever, while abdominal distention is less common. The most commonly affected abdominal regions are the hepatobiliary system, the peritoneum, and the ileocecal region, due to local implantation of the bacillus generally by the hematogenous route.6

If lymphadenopathies are detected in various sites, the differential diagnosis must include granulomatous lung diseases, such as TB, histoplasmosis, and sarcoidosis; connective tissue diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis; and cancer (lung cancer, metastasis, Hodgkin's or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma).7 TB with peritoneal lymph node involvement is usually seen in the peri-portal, peri-pancreatic, and mesenteric regions, causing local compression in these sites.8 Lymph node involvement in various locations accompanying the lung disease is usually more common in patients with HIV; this, however, and any other factor that would explain an associated immunosuppressive status were ruled out in our patient.

In our case, the radiographic study provided the key data, given the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms. Bilateral pseudonodular lung lesions are similar to those observed in metastatic involvement (“cannonball metastasis”), however, the socioepidemiological characteristics of the patient led us to consider the presence of TB. These lung lesions have also been described in coinfections with other pathogens, such as cryptococcosis,9 although this is more typical in immunocompromised patients. In our case, in the absence of pulmonary symptoms, sputum had to be induced to confirm the suspected diagnosis.

In conclusion, TB can occur with concomitant involvement in different sites, even in immunocompetent patients. It must therefore be included in the differential diagnosis when nonspecific symptoms with characteristic radiological data are encountered, particularly in patients with certain socioepidemiological backgrounds.

Please cite this article as: Gallardo Pérez E, Trasancos Escura C, Pacheco Tenza I, Massa Navarrete I. Tuberculosis pulmonar con presentación atípica en paciente inmunocompetente. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019;55:104–105.